|

From the South Eastern Gazette, Tuesday 14 April, 1846.

GRAVESEND PETTY SESSIONS.

Anne Wilkinson, a woman about 45 years of age, was charged with

breaking, on the previous night, a square of glass in one of the windows

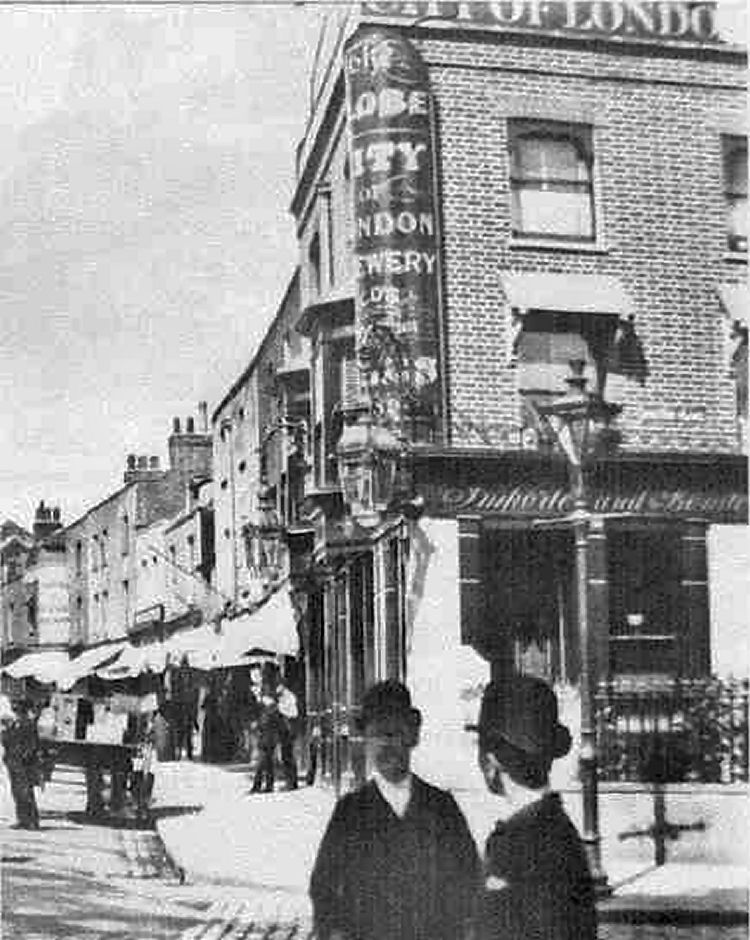

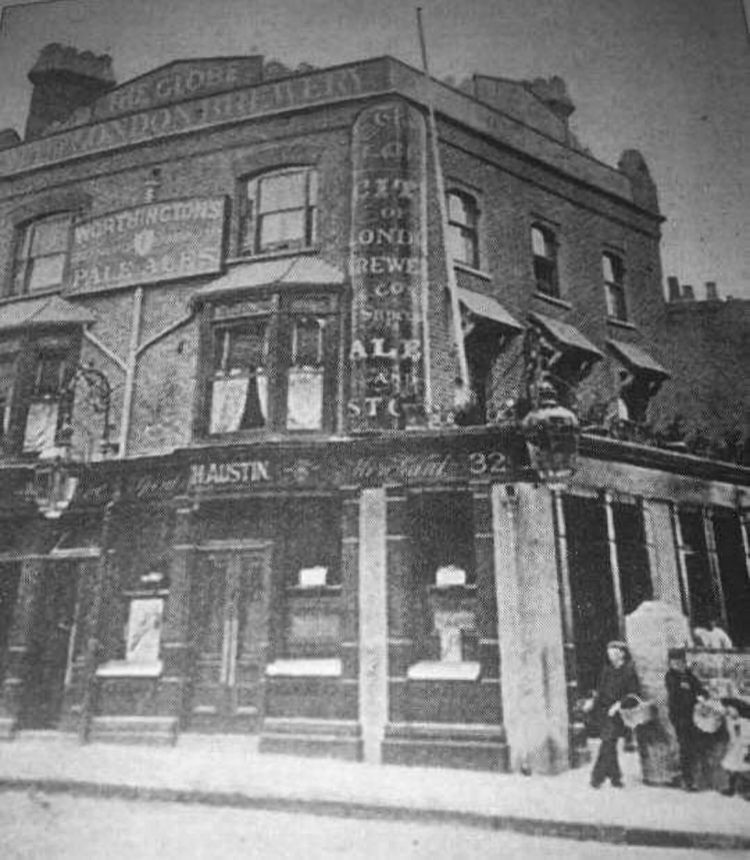

of the "Globe Tavern," Milton Road. Mr. Lott, of the "Globe," was about

to prove the charge, when the defendant stopped him by admitting the

wilful commission of the offence. To the Mayor's demand why he had done

so the defendant, in a deliberate but energetic tone, and in a state of

expression and manner that indicated a superior early education, replied

that she had walked thirty miles on the previous day without relief or

refreshment. On arriving in Gravesend she implored of several

housekeepers in the town to give her a night's lodging, and she had been

refused - that she at length, observing the complainant's house to be of

one of entertainment for travellers, asked him for a lodging for the

night, and he also refused both lodging and a morsel of refreshment -

that not having one penny to procure any food, she saw no resource for

her but a prison, and that to be taken there she had broken the window.

Mr. Oakes:- If you were in a state of destitution you describe, why not

go and ask for relief at the workhouse?

Defendant:- I will not deceive you gentleman, I have been in many

workhouses, and in every gaol in the kingdom, and I prefer, infinitely,

the gaols to the workhouses.

Mr. Oaks:- Why?

Defendant:- Because the society in a gaol is better - far better - bad

though it is, than that of a workhouse; besides, in a gaol I had

shelter, abundance, and protection, and then I could make myself useful.

In a workhouse I was ill-fed, ill-treated, and useless alike to myself

and others, and compelled to associate with worse and lower characters

than are to be found in a gaol, where such associations are not

permitted.

In reply to the Mayor, the defendant said that she was a native of Thame,

in Oxfordshire; that her father had been a teacher of languages, and

that she herself an embroiderer; that some years since, in consequence

of inability to get employment, she left her native place, and had been

at various times in great destitution, and was sent to several

workhouses, but found them invariably the same abodes of vice and

misery, and that in the course of the last six years she had succeeded

in procuring shelter, abundance, and good treatment in every gaol in

England, except that of Maidstone, to which she was now desired to be

sent. The last she had been as was Coldbath Fields, and she felt bound

to say that the prison was, in her opinion, the best regulated of any of

those she had occasionally resided in. The Mayor, after some

consultation with his brother magistrates, asked her whether, if she had

the means, she would go back to her native place. To this she replied

that she would much prefer going to Maidstone gaol; that if she should

go back, she could get no employment, and to avoid the contagious,

impure, and demoralising society of a workhouse, she should commit an

offence to be sent again to gaol. She therefore begged of the

magistrates to send her to Maidstone; to London she did not wish to

return at present, as she had been in every prison in the metropolis,

and she wished to try if Maidstone gaol was as well regulated.

The Mayor told her that she appeared to have a propensity for prison

discipline, and as she objected to go to her native place or to London,

the Magistrates would commit her for one month to Maidstone gaol.

Defendant, in a tone of disappointment, "One month - far too short a

time - but still I thank you, gentlemen." Turning to leave the Court in

custody, she exultingly exclaimed, "I'll die at least in a gaol and not

in a workhouse."

|