|

From the

https://www.express.co.uk By James Murray. 10 January 2022.

The WW2 pub trip that set a time-bomb ticking in the Thames.

AS THE MoD plans a £4m clean-up operation, the Express reveals how a

sea captain's night ashore 78 years ago put the estuary at risk of a

huge explosion and devastating tsunami.

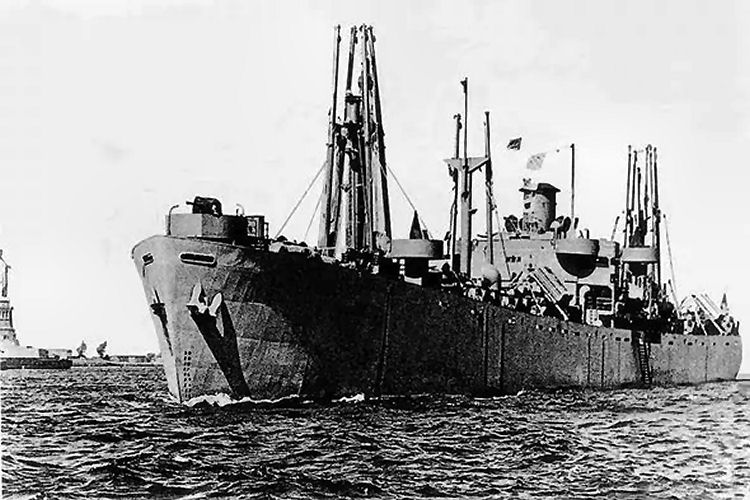

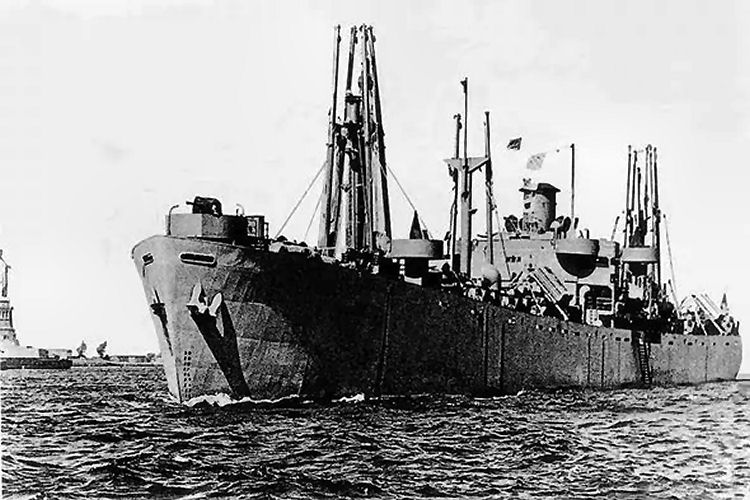

Thames Estuary and shipwreck masts.

The SS Montgomery could cause a tsunami that would 'flood London'.

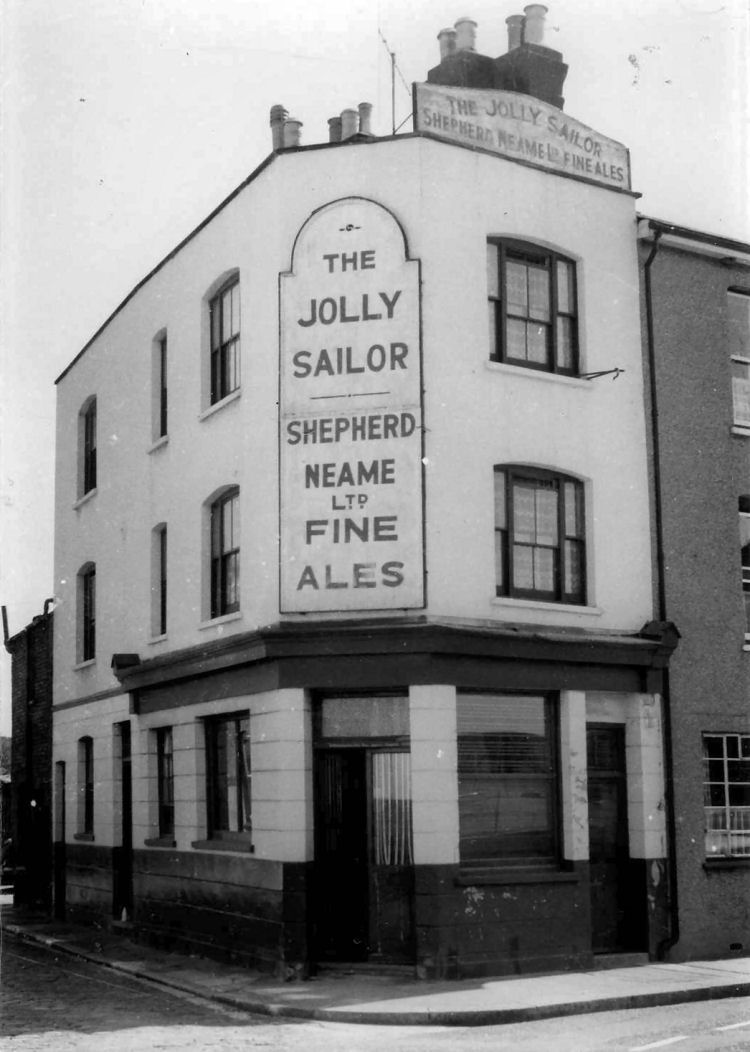

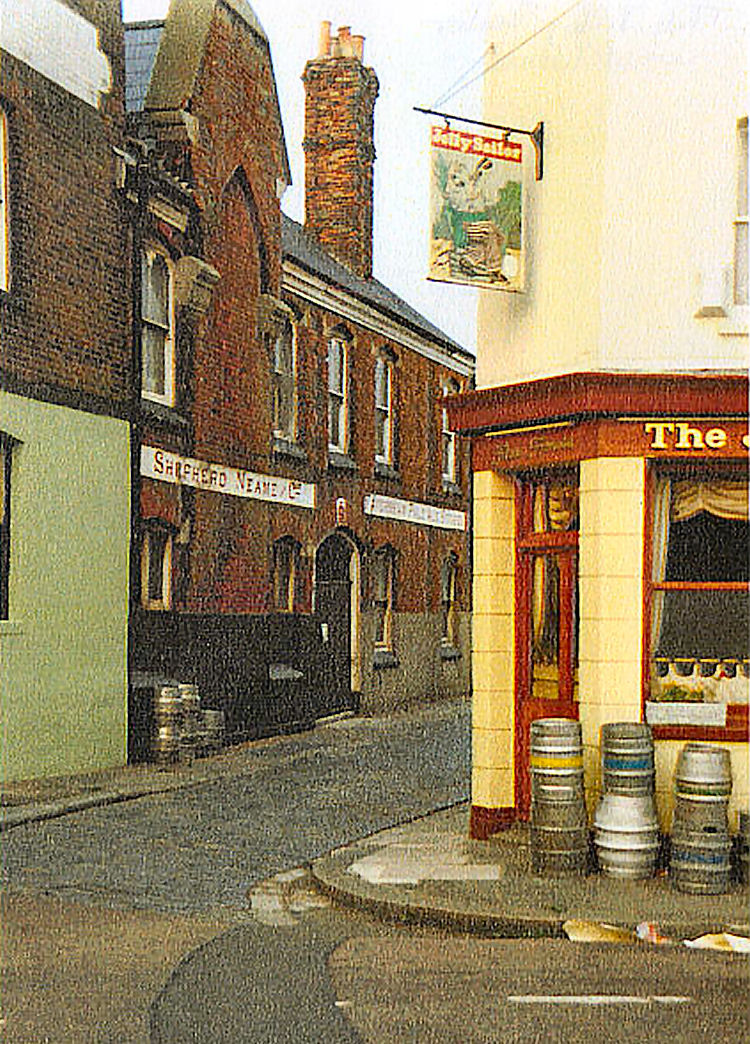

Settling down for a night in the "Jolly Sailor" pub, Captain Charles Wilkie could not shift a nagging worry about his ship, the SS Richard

Montgomery, which he had left anchored little more than a mile away off

the Kent coast in the Thames estuary. It was August 1944, just 11 weeks

after D-Day, and as history has shown, he had good reason to be

concerned.

The US-built cargo vessel was carrying 6,862 tonnes of bombs and waiting

to join a convoy of ships heading to Cherbourg, France, to replenish

Allied supplies. But a storm was already whipping up the waters of the

Thames estuary.

Wilkie, an American, had been directed to drop anchors by Royal Navy

Lieutenant Richard Wilsley but, concerned he could become grounded on a

sandbank, he and his boatman had gone ashore to seek a second opinion

from the local expert at Sheerness dockyard. Shipping controller

Reginald Coward agreed it would be safer to anchor where the estuary had

been deep-dredged and there were three solidly-anchored buoys to fasten

to.

But fate was already conspiring against Wilkie: the gathering storm made

it unsafe to risk a return journey in a small boat at night.

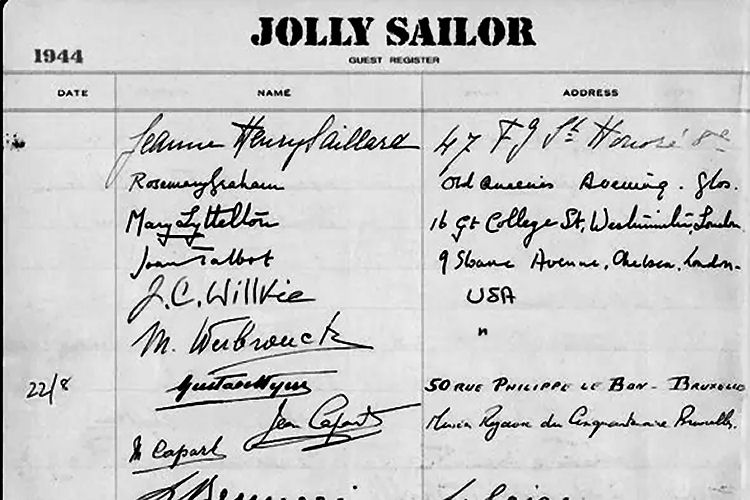

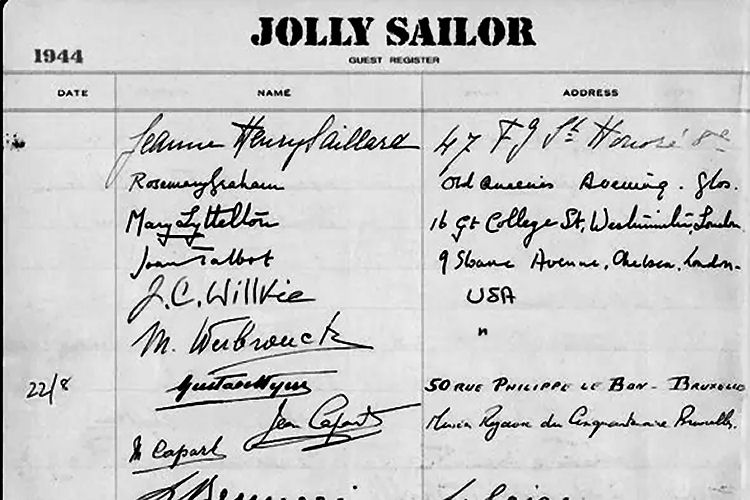

That is how J C Wilkie and his boatman came to sign in as guests at the

"Jolly Sailor" while his ship and crew were left under the command of his

first officer, according to historian Colin Harvey.

The SS Richard Montgomery in her prime. (Image: Colin Harvey).

Even as the captain slept in a room above the pub, in the Blue Town area

of Sheerness, a calamity was unfolding at sea.

The ship, buffeted by strong winds, was dragging its anchors easily

across the muddy seabed. By the time the skipper returned to his vessel

on the morning of August 20, she was firmly stuck on a sandbank, with no

chance of being refloated.

Now, 78 years on, the catalogue of clangers still haunts the people

living on the Isle of Sheppey, Kent, and those eight miles across the

estuary in Southend, Essex. For the wreck of the SS Richard Montgomery,

or Monty as locals call her, remains laden with submerged bombs

equivalent to 1,400 tonnes of TNT.

A leaked MoD report says a blast could produce a 16ft tsunami, which

would threaten lives - along with vital gas and oil installations on the

Kent coastline. An explosion "would throw a 300 metre-wide column of

water and debris nearly 3,000 metres into the air and generate a wave

five metres high". And historian Mr Harvey, 79, from nearby

Sittingbourne, Kent, is deeply concerned about the likelihood of such a

disaster as the wreck becomes more unstable.

The ship's three metal masts protrude above the water from the submerged

and crumbling deck, and are corroding badly below the waterline. If they

collapse into the munitions, they could trigger a huge explosion and

subsequent tsunami.

The pub’s August 1944 guest book showing Captain Wilkie ’s name. (Image:

Colin Harvey).

"Sheerness, the largest town on the Isle of Sheppey, is below sea level,

so you can imagine how much damage a 16ft tsunami would cause," says Mr

Harvey.

"When you look at the history, all this could have been avoided. The

ship was directed to anchor at a place where she could have rested on

the sea bed at low tide. She should never have been there in the first

place. Coward was absolutely right to suggest the captain move her, but

it was too late. If only Wilkie and Coward had put the plan into action

immediately, disaster would have been avoided."

He explains: "After spending the night at the "Jolly Sailor," Captain Wilkie returned to his vessel the following morning to see she had moved

position on to a large sandbank called Sheerness Middle Sand. She was

stuck there.

"A few days later the ship started to crack under the immense strain,

but the captain and crew stayed on board. They did manage to get some

munitions off-loaded but she broke in two and the last of the US

civilian crew abandoned ship.

"Stevedores remained on board for a few more weeks to get more munitions

off but then it became too dangerous. A list of what was taken off has

been destroyed so nobody actually has an inventory of that. Some

munitions were taken to Chatham and Sheerness but it is not clear what

happened to them then."

Local historian Colin Harvey with wreck in the background. (Image: Colin

Harvey).

An inquiry into the grounding was rushed, claims Mr Harvey. It heard

that nearby vessels reported seeing the ship moving in darkness but that

the first officer, who was on duty that night, was at a loss to explain

why he didn't wake up the captain.

The historian suspects the first officer could not tell the inquiry why

he did not wake the captain because Wilkie was at the "Jolly Sailor" pub -

and not aboard his vessel as he should have been.

"You have to remember this happened at a critical time in World War Two

when everyone was working under pressure," he says.

"This was a problem to come back to once the war was over, but it was

never properly resolved. All the munitions should have been taken off

soon after the war but it was ruled too costly and probably too

dangerous.

"However, the situation is not any better now than it was then. In fact,

it's probably a lot worse. Monty has been hit once by a vessel and there

have been more than 20 near misses. It is right by a busy shipping lane.

There are cracks and holes in the hull now, so munitions could

eventually escape.

A montage of sonar images of Monty on the Thames riverbed. (Image: Colin

Harvey).

"To safely remove the munitions now would cost about £300 million and

would involve building a massive enclosed structure around the wreck,

draining off the sea water and air, then pumping inert gas into the

enclosure to reduce the risk of explosion. It would be a massive

operation."

As part of his inquiries, Mr Harvey discovered a baffling, erroneous,

letter sent to Sheerness Council in 1962 from the office of the

Commander in Chief of the US Naval Forces in Europe, denying the

existence of the wreck.

Signed by a Lieutenant J S Cohune, the letter states: "On 20 August 1944

she [The SS Richard Montgomery] went aground at the bottom of the Thames

River Anchorage. Since only her superstructure remained visible, she was

declared a maritime wreck. She was raised and scrapped in April 1948 and

sold to Phillip's Craft and Fisher Company on 28 April 1948. Perhaps you

can keep this office posted as to the progress you are making in solving

the riddle."

Partly because of that letter, some locals in Sheerness jokingly refer

to Monty as the "ghost ship".

Others talk ominously of Monty's Revenge if she does blow, sending a

16ft tsunami into Kent, Essex and up the Thames.

In a partial fix, Briggs Marine, based in Fife, Scotland, will begin

dismantling the masts this June, supported by Royal Navy experts and 29

Ordnance Disposal Group in a £4.6million operation lasting two months.

"It will be extremely dangerous and I worry for those carrying out this

work. I also think they'll have to evacuate thousands of people

from Sheerness and Southend while it takes place," says Mr Harvey, who

gives talks on the world's most treacherous wreck. He understands the

masts will be held in place by cranes on salvage vessels but they will

almost certainly have to be cut off the deck area below the waterline,

possibly with divers using oxy-acetylene torches.

"This MoD report has highlighted the risk of a masts collapse causing an

explosion."

It is the combination of munitions on the SS Richard Montgomery that

alarms salvage experts, with white phosphorus smoke bombs along with

high explosives.

Munitions consultant Andrew Crawford conducted a risk assessment in 2009

and described 2,600 cluster bombs as armed.

INSIDE each bomb is a stainless steel tube with a stainless steel ball

at the top, held in place by a spring with a Mazak (zinc aluminium

alloy) pin. Although stainless steel does not corrode, Mazak dissolves

over time. This means the ball would roll down the tube, arming the

bomb. |