|

Sheerness Guardian 15 January 1859.

DREADFUL MURDER! AT QUEENBOROUGH.

On Tuesday evening last, a most painful tragedy occurred at

Queenborough, which has created immense sensation, not only in the

town itself, but in Sheerness also, as well as in the island

generally. What renders the occurrence more tragic is that the

murderer is not 20 years of age, and his innocent victim not yet 16.

The particulars of the case may be thus summarily stated.

A young man named Frederick Prentice, has for some time been lodging

at Queenborough, having formerly been engaged as a labourer on the

Sittingbourne and Sheerness Railway; subsequently employed by Mr.

Josiah Hall, of Queenborough; and latterly by Mr. Moxon, the

contractor for the batteries, at Sheerness.

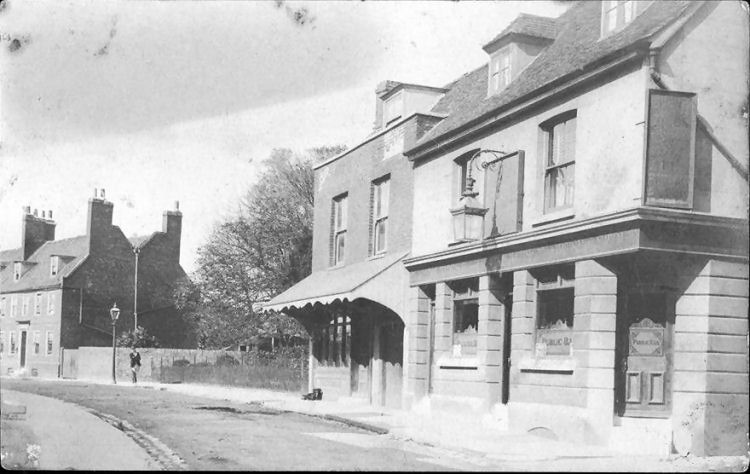

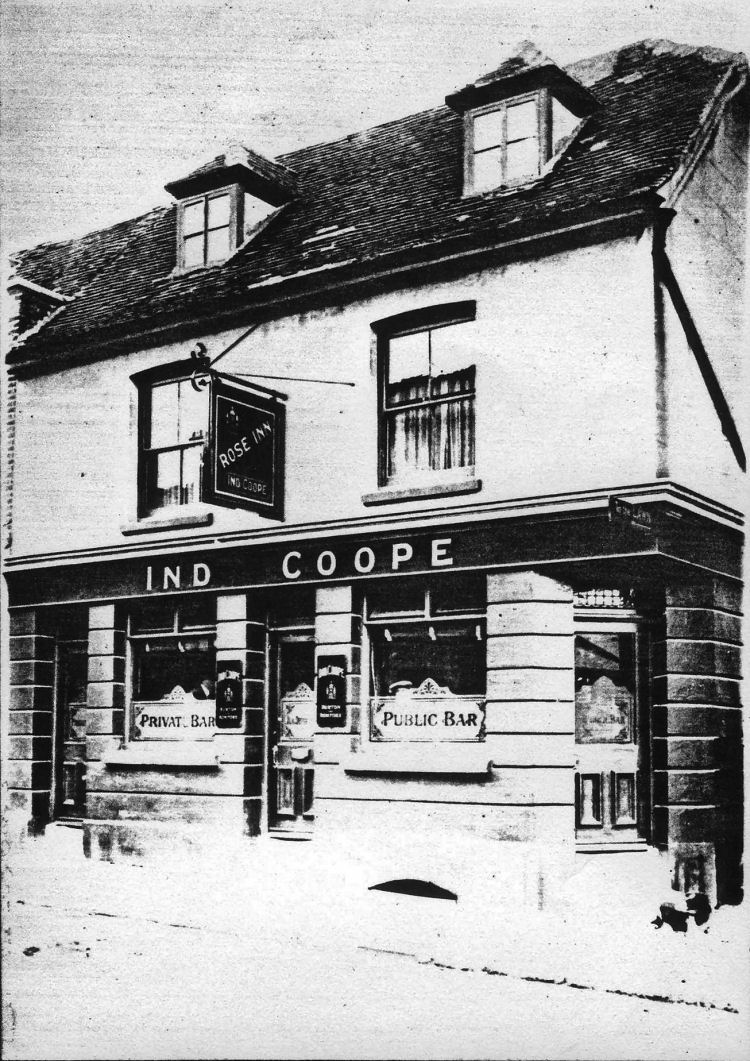

It appears that he had formed a strong and ardent attachment to a

young female of the name of Emma Coppins. The latter never seems to

have encouraged his attentions, although it is evident that she

allowed him to clean knives for her whilst she was servant at the

"Rose Inn," at Queenborough, and had subsequently accepted "nuts and

oranges" from him. Still it is quite certain, that his overtures

were never acceptable, and that latterly they had become offensive,

and that she had continually tried to evade his company. This was

more particularly apparent on Sunday last, when she "ran away and

hid herself from him," whilst he was following her, with the

apparent intention of pressing his company upon her. This conduct

appears to have irritated him, and from this moment the idea of

murder seems to have been suggested to his mind. At all events, on

Monday morning last, a razor was missing from the house in which he

lodged, and this identical razor, as will be afterwards seen, was

the destructive weapon which consummated the tragedy! Nothing further

occurred until Tuesday. On the evening of that day, Prentice was

seen by several individuals near to the Town Hall, at Queenborough,

more particularly by T. W. Fisher, at or about 25 minutes past 8.

Adjoining the Hall is an "alley" or passage leading on to

Queenborough Green; and up this alley, Prentice was seen to go. It

further appears that at or about the same hour of the evening, Emma

Coppins was in the constant habit of passing by this alley to the

"Ship" Inn, to purchase a pint of porter for her master, Mr.

Stephens. This was doubtless known to Prentice. At all events, the

young girl passed by the alley on the night in question, and within

a few minutes of the time Prentice was seen to be there. When close

to the alley, she appears to have been pounced upon, when her throat

was cut, with such precision, as to have instantly produced death,

and that almost without a struggle. Indeed but minute or two had

elapsed since parties had passed the spot; where the body was found,

and the discovery of the murder. A scream certainly seems to have

been heard, but no scuffle could have taken place, for the very jug

in which the beer had been obtained, was actually found unbroken and

with some of the beer in it. The first idea that was suggested by

the discovery of the body was, that some one had fainted, for one

witness had actually seen the woman fall, and had noticed no one

near. Other parties were in the immediate vicinity, or had been

there but moment or so before — more particularly the mail-man,

Kite. A light, however, having been obtained, the dreadful fact was

soon disclosed, that Emma Coppins had been murdered. Her throat was

cut from near the windpipe to about 4 1/2 inches backwards, and some

considerable depth. The body was warm, but the living breath had

fled, further inspection led to the discovery of man's cap and also

an open razor with blood on the blade of it — the razor we have

before alluded to. The lifeless body was removed to the home of her

aged father — an agricultural labourer with a large family.

Underdown, the town constable, immediately gave information to the

police. About 9 o'clock, Sergeant Ovenden, of Sheerness, was in

possession of the facts, and with the utmost despatch made the whole

of the force turn out. The men were located in different parts of

the district, and information was sent to Superintendent Green, of

the Faversham division, to bring up the force under his command, to

the banks of the Swale. This he promptly did, and planted men at

Harty Ferry, Elmley Ferry, and King’s Ferry. The rest of his men he

placed on the surrounding wall, so as to prevent the possibility of

the prisoner getting out of the Island without being detected. A

great number of the male population of Queenborough — like true

Englishmen — also volunteered their services to Sergeant Ovenden,

and after being divided into parties, went out to scour the fields.

It may be well to state that suspicion fell on Prentice, the moment

the murder was discovered; and that this suspicion was not long

without confirmation. The active measures that had thus been

adopted, soon led to the arrest of the prisoner. About one o’clock

on Wednesday morning, Henry Ford, P. C., 174, was proceeding from

the Half-way houses, to Mile town, when he saw the prisoner going on

before him. To make use of Ford’s own words, "I did not at first go

up to the man, because he did not answer the description with which

I was furnished. I went on about a rod and a half and stopped; I

then turned round and threw my light upon him. He said "are you a

policeman?" I replied yes. He then said "I am your prisoner, my name

is Prentice," adding "I wish some one would kill me." He then asked

me if "she was dead." Thus clearly convicting himself, if not

positively acknowledging his guilt. He shook violently at the time;

appeared terribly agitated, and was scarcely able to stand; indeed,

the policeman had to support him whilst he was being handcuffed. It

is inferred that the prisoner had very nearly been arrested at an

earlier hour, as his clothes were covered with mud from being in the

ditches, and from which he had apparently been driven by his

pursuers into the main road. We have thus far briefly narrated the

particulars of this shocking tragedy, until the time the perpetrator

was in the hands of justice, and secured in the Sheerness lock-up.

Whatever other facts have transpired, are given in the evidence

produced at the examination of the prisoner and at the Coroner's

Inquest.

EXAMINATION OF THE PRISONER.

The prisoner was brought up on the charge on Wednesday afternoon, at

the Town Hall, Queenborough, before L. S. Magnus, Esq., (Mayor) and

S. J. Breeze, Esq.; the former gentleman having been telegraphed for

from London for the occasion. The Rev. R. Bingham was also on the

bench. The Hall was densely crowded throughout the hearing of the

case, and the greatest excitement prevailed in the town.

The prisoner was brought from Sheerness in a covered phaeton in

custody of Superintendent Green, and Sergt. Ovenden, and was also

accompanied by Mr. Stride, surgeon at Sheerness. A great crowd had

assembled to witness his departure from Sheerness, as well as to

catch a glimpse of him on his arrival at Queenborough. He is a young

man, of short stature, sallow complexion and stiffly built; he has a

very fair character at Queenborough, for his steadiness and general

conduct, with the exception of his being somewhat morose in

disposition and reserved in character. It was with some difficulty

he was able to walk up the stairs of the Court and not without being

supported. He was then placed on a chair in front of the bench. He

hung his head down during the whole of the proceedings, without even

raising his eyes or uttering a word. He shook violently, sobbed

audibly and appeared to feel his guilt most acutely. The folluwing

evidence was then produced. On being asked after the deposition of

each witness whether he had anything to say, he simply shook his

head and that but faintly.

Previous to the hearing of the case, Mr. Craven, solicitor, of

Sheerness, was solicited by the Mayor and Mr. Breeze, to act on

behalf of the Town Clerk, who was absent in town. Mr. Craven

accordingly took his seat and indicted the depositions with

considerable success.

Richard Coppins deposed, I am a labourer, and father of the

deceased. I know the prisoner. I was in doors last night at

half-past eight. The deceased was then alive and in my house; she

brought a dress to wash. She had a jug with her and was going to the

"Ship Inn" for some porter. I did not see her again until after her

death. She would have been sixteen years of age in April next. I did

not see her last night after her death because my feelings would not

allow me to look at her. There was no particular intimacy between

the prisoner and my daughter; he wanted to be friendly with her, but

she did not wish to have his company. He was always running after

her; he used to watch her, but she repeatedly said she did not want

him. That is the body of my daughter that Mr. Stride examined this

morning.

William Bills, junr., landlord of the "Ship’ Inn," saw Emma Coppins

on Tuesday evening, about half-past eight o’clock. He served her

with a pint of beer, and she went away. She was in the habit of

coming to his house for porter every evening. It was about forty

rods from his house to the place where the deceased was found.

John Kite, mail-driver to Sittingbourne deposed:- I arrived at

Queenborough with the mail cart about half-past eight on Tuesday

evening and drove past the Town Hall to the Post Office, I did not

see any one then, but a minute or so afterwards while I was putting

my bag into the mail-cart I heard some one give a scream. I took my

time bill and turned my horse round to come out of Queenborough

again. My horse made a dead stop on coming up to the body of a

female on the road.

I saw a woman near, going into her house. I called out "Missus" and

told her that some one had fainted. I asked the woman to go and see.

She did so and I drove off under the impression that the body was

that of someone who had fainted.

Thomas James Underdown constable at Queenborough was called for at

half-past eight o’clock by Mrs. Knewstub. She said a woman had

fallen down in a fit. I made immediately for the spot which was

about three yards from the Court Hall Alley. I saw Emma Coppins

lying on her back. I saw that her face was covered with blood by

means of a lantern. Some other parties were there when I went up. I

felt the hand of the deceased and it was quite warm. We then lifted

her up and saw that her head fell forward and backward and perceived

that her throat was cut. I sent information to the police. A man's

cloth cap was found near to the spot, which I now produce. I

afterwards picked up an open razor about three yards from the body,

which was stained with blood on the blade. I then handed it over to

Charles Curd, P.C. 146.

Natlaniel Firman, a boy fifteen years of age, had seen a woman fall

about three yards from the Town Hall Alley, and had heard her groan,

but did not see any one near to her.

Charles Curd P.O. 146, deposed as follows:— About twenty minutes

past nine on Tuesday evening, I was informed that a murder had been

committed in the street. I immediately made haste to the spot, when

I saw the deceased being removed upon a stretcher. Several people

were there, and said that a murder had been committed, and that I

must go for assistance. I saw a cap and razor on the ground. A man

picked up the cap, and Thomas Underdown picked up a razor and gave

it to me. I kept it in my possession. Both the blade and the handle

were covered with blood. After I saw the body home, I went to see if

I could find Sergeant Ovenden at Sheerness. We both returned

together to Queenborough.

Phoebe Parker said I have known the prisoner for about 13 mouths, he

has been lodging with me. I saw him last on Tuesday afternoon about

half-past three. He was then dressed in light new corduroy trousers,

blue pilot jacket and blue jacket slop underneath; with black cloth

cap. The cap now produced is exactly like the one he used to wear. I

have heard the lodgers pass jokes upon him about a girl living at

the "Rose." The prisoner had no razor of his own but used one on

Sunday afternoon last belonging to John Colley — another lodger. I

have not seen the razor since he had it. It is not in my house now.

I have searched everywhere. I missed it on Monday morning. It was a

white handed razor and I said to the prisoner that I did not see

Colley’s razor but he made no reply. It was exactly like the one

produced, but I cannot swear to it, my husband can. The same witness

also identified the pilot jacket as belonging to the prisoner.

James Parker, a time keeper on the Sittingbourne and Sheerness

Railway, said, I know the prisoner. He has been lodging in the same

house with me for some months. I remember Sunday morning last; I

shaved with a white handed razor, and I also saw the prisoner shave

with it in the afternoon, I have not seen the razor since.

[The razor was then produced.]

That is the razor; I know it by its marks — a large gap in the

middle and a smaller one beside; also by a name on the back of it

like "Sundry," or something beginning with S. The name is on the

back of the blade. I enquired for it last night about six o'clock.

My wife said she had searched for it and could not find it. Have

seen Emma Coppins, and have often laughed at the prisoner about her.

I do not think she wanted him.

Margaret Calligan, (a young girl) saw the deceased last Sunday

evening. She asked her if she had seen Emma Edwards. She (the

deceased) said she was rather frightened as there was a man watching

her, and that she could not get away from him. The man had his back

towards them, and deceased said that was the man, but witness could

not swear the prisoner was the party as she did not see his face,

but he was dressed in blue coat, light trousers, and had a cap on.

Robert Purnell, stonemason, had known the prisoner for about 15

months. Saw him last as he was coming from the "Ordnance Arms,"

about a quarter-past eight on Tuesday evening. I was talking to a

lad outside the Town Hall. Soon after the prisoner came by and spoke

to me. He asked how I was and I enquired if he was in work still. He

said he had been discharged on Saturday but that the foreman of the

works had said he could go to work again if he liked, but he should

not. After that I turned and went up the street and he walked away

from me. I went up towards the church, he went down towards the

river. I have not seen him since until brought into court. He

appeared to be dressed in a fustian jacket, but I am sure he had

corduroy trousers and also a cap on. I did not observe anything

particular in his conversation.

George Wightman, a labourer, knew the prisoner and saw him about a

quarter past 8 opposite the Court Hall with the witness Purnell.

Purnell went away before me, and left me talking to the prisoner I

left him four or five minutes after Purnell had gone. The prisoner

went across into the Court Hall Alley.

Thomas William Fisher, mariner saw the prisoner on Tuesday evening.

He was leaning against one of the pillars of the Court Hall. It was

then 25 minutes past 8. I was going home. It took me about a minute

to walk home. I stayed in the house two or three minutes. I heard a

scream like a woman’s voice. On hearing the scream I went out. A

neighbour said some one was in a fit. I ran down the street and

found the deceased. Witness also confirmed other particulars of the

evidence already given.

Henry Ford, P. C. 174, of Sheerness, said about half-past nine.

Sergeant Ovenden came to my house and from the information I

received I went specially in search of the prisoner. I did not know

him, but had a written description of him. About one o’clock this

(Wednesday) morning. I was going from the "Half-way house" towards

Mile Town, Sheerness; and when about half-way between the two places

I saw a man going on before me. He was on the opposite side, and was

dressed in a blue reefing jacket, had a handkerchief on his head,

and wore corduroy trousers. When I got up to him and was opposite to

him, I turned my light upon him, but he did not answer the

description with which I was furnished I did not go across to him at

first; but I afterwards did. The description I had was, that he was

dressed in white smock frock, with blue work round the wristbands

and collar. I went on for about a rod and a half, and I then

stopped, and thought that I would go and look at the man more

minutely, and see who he was. I did so and again turned my light

upon him. He said, "are you a policeman?" I replied yes. He then

said, "I am your prisoner; my name is Prentice." I knew then that he

was the party I was looking for. He said, "I wish some one would

kill me." He afterwards asked me, if she was dead." He did not say

who. I replied that I had not seen her. I then took him in my

custody, to Sheerness lock-up. I found marks of blood upon his

trousers and also marks of blood upon the back of his right hand.

The pilot jacket I produce, has marks of blood on the sleeve. (Mrs.

Parker, identified the jacket, as belonging to the prisoner).

Edward Stride, surgeon, of Sheerness, deposed that he had examined

the body of deceased, and that she had died from hemonhage, caused

by an incised wound in an horizontal position, extending from near

the windpipe to about 4 1/2 inches backwards. The wound must have

been inflicted by a sharp instrument across the throat. It would

cause instant death. He had seen the prisoner and examined his right

hand and found blood upon it. There had been a good deal. He also

deposed to finding blood on the prisoner’s trousers and jacket.

Witness in answer to an enquiry from the bench, also deposed to

accompanying the prisoner from Sheerness and that he was merely

suffering from extreme grief. He had asked the prisoner if he was

hungry, and he had shaken his head to signify no. He had asked him

if he was cold, when he shook his head in the same manner. He

considered that the prisoner had heard the whole of the examination

of the witnesses.

At this stage of the proceedings, the Court adjourned until

half-past eight, in order to afford time for correcting and

preparing the respective depositions for the signature of the

witnesses. This being done the Court was reopened the prisoner was

then asked if he had any thing to say in reply to the charge and

signified through Mr. Stride surgeon, that he had not. He was then

convicted of the charge of Wilful Murder, and ordered to be

committed to take his trial for the same at the next Maidstone

Assizes. The prisoner was then removed to the lock-up at Sheerness,

until the holding of the Coroner’s inquest.

The proceedings commenced about three o'clock, and it was nearly ten

o’clock before they were concluded.

THE CORONER'S INQUEST

Was held on Thursday morning, at 10 o'clock, at the "Ship Inn,"

before T. Hills Esq, and the following jury:— The Rev. H Bingham,

(foreman), Messrs. Josiah Hall, Ebenezer Absale, Thomas Moss,

Charles Hall, William Videon, R. B. Cole, William Cole, Thomas

Brightman, Edward Champion, Thomas Underdown, William Dodd, and

William Rice.

The greater part of the evidence produced on the preceding evening,

was recapitulated and on examination of the various witnesses, the

following additional facts were elicited, namely, that when the

deceased was found, she was lying in a pool of blood, and that the

jug was standing near to her unbroken, and a portion of the beer in

it; P. C. Ford, also further deposed, "when I encountered the

prisoner he had both his hands in his pockets. I told him to take

them out. He replied, I shall not hurt you. I said, no, you don't

seem in a fit state to hurt any one. He was trembling with

agitation; so much so that I was obliged to hold him up and support

him, whilst I was handcuffing him."

The following additional witnesses were then heard:—

George Jenkins, landlord of the "Rose Inn," at Queenborough, stated

that the departed had some few months ago, lived with him as

servant; that the prisoner had been accustomed to frequent his

house, ever since he had been at Queenborough, but more especially

during the time the deceased was in his employ; also, that they

seemed on friendly terms and that on one occasion the prisoner had

assisted to clean knives for the deceased. He knew of no further

intimacy.

Emma Edwards (a young girl and a companion of the deceased) deposed

that she knew Emma Coppins well and that on Sunday evening they were

at chapel together They afterwards went down the street; they saw

the prisoner standing at the door of his lodgings. He followed them;

they crossed the road and he continued to follow them. The deceased

then ran away and hid herself. Before this, the deceased had told

witness that she didn't want the prisoner. No conversation took

place between them on this occasion, but on a previous occasion, she

had seen the prisoner give the deceased some nuts and two oranges.

These were the only additional depositions that were made. The

prisoner, as on the preceding day, preserved the same sullen

demeanour, refusing either to ask any questions or to answer any,

except by movements of the head. Mr. Stride, however, stated that he

was perfectly sensible of the proceedings, and could have replied if

he felt willing.

The Coroner having read the respective evidence, then called upon

the prisoner to say anything he wished to say, giving him the usual

charge, that what he might state would be produced in evidence

against him. The prisoner manifested no disposition to alter his

demeanour and said nothing.

The Coroner then briefly addressed the jury observing, — that he did

not think it necessary to trouble them with any more evidence on

this occasion. The matter appeared to be comprised in a nutshell.

The deceased was a girl fifteen-years of age, and lived in service;

and between her and the prisoner, it was quite clear that there had

been some intimacy, though perhaps not very great. Mr. Jenkins, the

landlord of the "Rose Inn," and with whom the deceased had lived,

had noticed that the prisoner was in the habit of going to his

house, more than he was accustomed to do, while the girl lived

there, and had on one occasion assisted her to clean some knives.

This was a fact of some importance, as it showed an intimacy had

existed between the parties. There was also the evidence of Emma

Edwards, to show that on Sunday evening, the prisoner was following

them, and that the deceased evidently, went and hid herself, for the

purpose of avoiding him. Therefore there was positive evidence, of

an intimacy existing. Then came the fact, which was clearly proved,

that the girl was killed by some sharp instrument, like a razor.

Then followed the evidence of Fisher and Wightman, that the prisoner

was seen near the scene of the murder, immediately before it took

place. Underdown, the constable proved, that he saw the jug, and on

making a search, a mans’ cap was found, and also a razor. With

regard to the cap, they must take the evidence as it was. If they

thought that they had good grounds for believing, that it was the

prisoner's cap, they would take that as proof of identity. With

regard to the identity of the razor, there was no doubt at all. Mr.

Parker, positively identified it as the one left at his house. He

(the coroner) thought, they would therefore take the evidence as to

the razor and cap, as being conclusive. The razor was seen on

Sunday, and on Monday morning missed. Then came the very important

fact, that when Ford, the policeman, took the prisoner into custody,

he made use of this remarkable expression, "is she dead?" clearly

referring to the circumstances which had taken place; indeed, the

whole of the evidence, of the policeman Ford, left but little doubt,

as to the part the prisoner had taken in the murder. If there was

any point that was not explained or clear to them, he would be glad

to explain it. He wished them however to bear in mind that they were

not trying the man. It was simply for them to say whether the

evidence was sufficiently conclusive, to justify them, in committing

him on the charge. As to whether it was a case of murder, or of

manslaughter was a subject for another jury to decide. It was

however for them to say, whether the deceased, met with her death,

from the hands of the prisoner; if so, there was but one course for

them to pursue, and to find a verdict against him.

The Coroner further observed that as the prisoner had made no

statement, they had no other evidence than such as the prosecution

presented.

The jury were then called upon to consider their verdict, and

unanimously and immediately pronounced a verdict of WILFUL MURDER

against the said Frederick Prentice.

Throughout the hearing of the evidence the prisoner was accommodated

with a seat, and did not lift his eyes from the ground, or appear to

look upon any one or notice anything. He appeared, however, more

composed than on the preceding day, and more recovered from his

terror-stricken aspect. He heard the verdict with the same stolid

demeanour he had displayed throughout, and was immediately

afterwards removed to another room. The Rev. K. Billingham, then

requested permission to have an interview with the prisoner, with a

view we believe to giving him some ministerial and suitable advice.

The request was acceded to — a policeman of course being present at

the interview.

The warrant for the prisoner's committal to Maidstone gaol was then

made out and he was shortly afterwards removed.

A large concourse of people were assembled to witness his departure,

but there was no manifestation of popular feeling, apart from

interested curiosity.

The prisoner has scarcely spoken to any of the prison officials or

constabulary since his capture. He has taken but the smallest

portion of food and has ever since his arrest been apparently

suffering the most intense agony of mind and prostration of body.

Indeed it was found requisite to administer repeated doses of brandy

and water to him, on Wednesday and Thursday in order to support him

and enable him to undergo the ordeal of the investigation. Doubtless

much of this may be assumed, but it is nevertheless true that much

of it is real. Notwithstanding he slept Well the last night he spent

in the Sheerness lock-up.

FURTHER PARTICULARS.

Since writing the above we have received the particulars of the

interview between the Rev. R. Bingham, and the prisoner; they are,

however, of such a private nature as to preclude publication. We

may, notwithstanding state that when the Reverend gentleman entered

the room, the unfortunate criminal held out his hand to him and

burst into tears. A long conversation then endued, in which the

prisoner manifested every disposition to be communicative, and would

doubtlessly hare made a clean breast of the whole affair had be been

pressed to do so. Mr. Bingham contented himself with directing the

prisoner’s mind to the state of his guilt, by suitably exhorting

him, and by engaging with him in devotional exercise. The prisoner

was deeply affected, and there is but little doubt but that he will

make a full confession of the crime, and plead guilty to the charge.

It is said, (we believe on the prisoners own statement) that he has

neither father nor mother alive; that the only relation he has is a

sister, and that she resides at a distance, but he refuses at

present to say where.

|