|

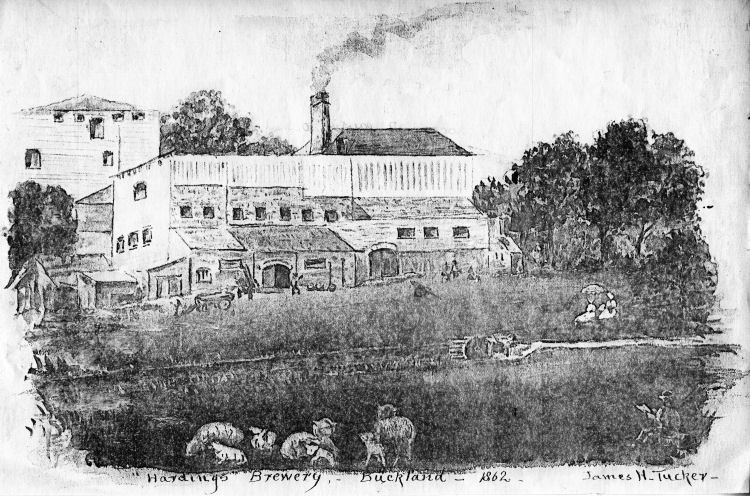

The End of a Brewery.

From The Brewing Trade Review January 1963

A ruthless demolition gang have been at work on the

old brewery. The wooden sides have been pulled down by steel cables; the

flint walls levelled, and the old flag-stoned cellar, many feet below

the level of the nearby stream; has been filled with rubble. Shortly a

modern factory will rise on the site.

Time was when the brewers

in their red stocking caps were busy about their vats, and horse drays

left the premises with full barrels for the local inns. But the last

traces of an old time brewery will soon have disappeared.

Through the ancient town of Dover, nestling in a deep chalk valley

between the famous white cliffs, there runs a brisk little river, which,

rising about three miles inland, tumbles over a number of falls, and

eventually finds its way into the docks, having run for some of its

latter course under buildings and streets.

Until the coming of steam

power, these various falls had considerable economic

value, and, from the time of the earliest settlement of a civilised

community on the stream, have been harnessed to drive water wheels to

provide power for various industries. On this river Dour, there have

been flour mills, timber yards, paper mills and breweries; all dependent

upon the tumbling chalk stream for their power.

The very ancient building recently demolished was one of the last

remaining breweries in Dover. Although it has not been used since about

1890, it has for many years been owned by the proprietors of a

neighbouring flour mill, who have preserved it in the same state since

the day when the last brew of ale ran out of the the vats some 70 years

ago.

The origins of the building are lost in obscurity; but it is thought to

have been at one time a flour mill. In the late eighteenth century it

was a paper mill, and about 1846 it became a brewery; known as Harding's

Wellington Brewery, possibly taking its name

from the Duke, who was at that time Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports.

A small waterwheel drove a pump which drew the liquor from a well; and

also drove a grinder for the malted barley. This wheel, 18 ft. 6 in. in

diameter, was situated on the backwater stream of the flour mill, and

could presumably only run when there was an excess of water, or by

mutual arrangement with the miller. The wheel has been kept in good

repair, and at the moment of writing, although no doubt doomed to be

broken up, is still in running order. The large gear wheel on the side,

drove a small pinion on a shaft

which extended about 35 ft. under ground to the brewery building

situated off to the left of the picture.

The writer is (perhaps unfortunately) more familiar with the end

product of brewing than the process thereof; but among other equipment in the

building were a number of vats on the first floor, protruding into the

cellar below; and a furnace heating a large copper set in brickwork.

Above this was a tank, from which the copper was filled.

Three of the vats had a diameter of 5 ft., and one, 6 ft. 9 in. The

brick seating of the copper (removed some years ago) was

7 ft. 6 in. No doubt the output from this brewery was small, even for

those days.

Whether the building made a satisfactory

brewery is possibly open to question, since as a paper mill the top

storey, of wood, was so constructed that sliding boards could be

opened to admit a draught of fresh air for drying the paper. Even when

closed, the building must have been a draughty one in windy weather. But

ill adapted or not, it became one of Dover's thriving breweries, of

which there were six in the town in the mid nineteenth century.

In 1890

brewing ceased; but my father tells me that as a boy he can recall the

brewers working in their red woollen caps, and the very pleasant aroma

which hung round the building! Its proximity to the flour mill was no

doubt an attraction to the dusty, dry throated millers. The enormous

technical strides in the industry over the past 50 years must make this

old brewery appear like a museum piece; but that it should have been so

long preserved, with its splashing wheel, its hooped, oaken vats, and

ancient furnace, is not without interest; and who is to say that its

product was not as well enjoyed by the thirsty in the mid-nineteenth

century as the modern

beverage is today?

|