|

From an issue of Bygone Kent Vol 15 No 4. October 1994.

DEATH AT THE DRUIDS

By Julie Deller

A good public house provides far more than liquor. It is a port of

call for locals, friends and street acquaintances meet there, presided

over by a landlord who acts out his role as Mine Host and there may even

be a pretty barmaid to make the older gentlemen think - for a while at

least - that they are young again! A pub needs to be a comfortable and

happy place. This is the story of one which was neither.

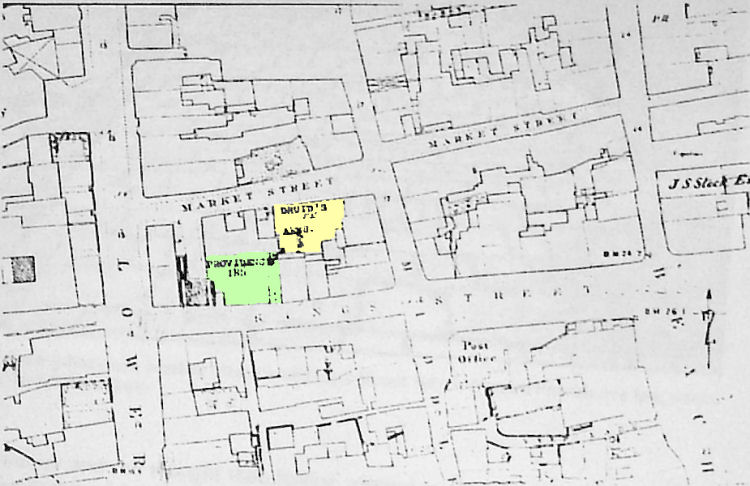

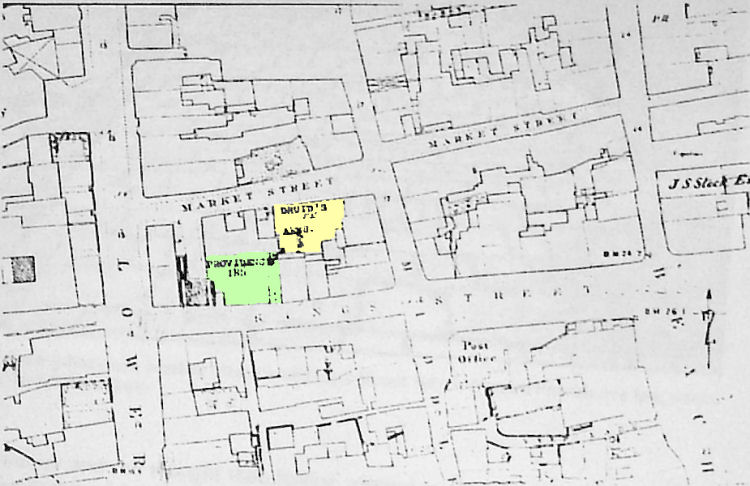

In October 1901

"The Druid's Arms," a Thompson's house in Deal's old Market Street, became

the scene of a most miserable death. It may not have been reported as a

tragedy, but for those who knew the landlord it was a tragic ending for

his life.

Mr and Mrs Browning had lived and worked at the "Druid's Arms"

for thirty two years. It was, of course, far too close to the "Providence

Inn," it most popular public house where whisky was served from six in

the morning until eleven at night. Tripe and onions was a dish always on

the Bill of Fayre and the pub also sold milk. Doubtless the Deal boatmen

gathered there during those long opening hours and there Is little doubt

that "The Providence Inn," also a Thompson house, did a better trade than

the "Druid's Arms."

William Browning worked on the beach helping to launch

the boats for fishing in winter and trips to the Downs for summer

visitors. During August of 1899 he broke his leg. Unable to carry on his

boat work he began to worry as money became short.

In turn Mrs Browning

worried about her husband. She suggested he went to the doctor to gel a

tonic to 'brace him up', but he refused, although, as his wife said, he

knew that he was just not as he used to be - not himself. He was always

tired and left his wife to serve the few customers who came into the

bar. They began to discuss leaving the pub for a less tiring kind of

business. A nice little tobacconist's shop, where they could sell

mineral waters, seemed a good idea, yet Mr Browning, feeling depressed,

could not make the decision. Finally, after two years of poor health, he

agreed to give notice to the Brewery.

The morning before they were due

to leave the "Druid's Arms," Mr Browning told his wife that he had stomach

pains and diarrhoea, for weeks he had eaten very little and slept less.

On that gloomy October afternoon Mrs Browning made a pot of tea and gave

a cup to her husband who sat by the fire without speaking. Someone was

heard coming into the bar, so Mrs Browning left her husband sitting by

the light of the fire, to greet Mr Wraight who was a friend and anxious

about Mr Browning's health. When Mrs Browning told him how poorly he was

Mr Wraight said he would like to buy him a drink and Mr Browning then

came from the kitchen and into the bar. He spoke to Mr Wraight and

accepted his offer saying that he would have a glass or beer with some

ginger beer, but his wife said that it was not good for his stomach

upset, so Mr Wraight said 'Have a little drop or brandy - hot'. Mr

Browning shook hands with Mr Wraight and returned to the kitchen where

he once again took up his seat beside the fire. The room was dark, as

Mrs Browning had not lit the gaslight. She gave her husband the brandy,

which she had warmed, and suggested that he should go up to bed if he

felt no better. Her husband said: 'I don't want to go to bed. You come

back as soon as you've served; don't stop.'

Mrs Browning returned to the bar, lit the gas there and washed up a few

glasses from around the room, chatting to a woman friend and Mr Wraight.

After about ten minutes she excused herself saying that her husband was

sitting in the dark and she must light the gas bracket in the kitchen.

Soon after she was to return to the bar shrieking 'Fetch Mr Wraight.

Something's wrong'.

Something was very wrong indeed. Mr Browning had

hanged himself. Mr Wraight dashed out after the distracted woman and saw

the body of Mr Browning suspended from a beam in the outside closet. He

quickly cut him down and did his best to revive him but, after a few

breaths, he was soon quite dead.

An Inquest was opened on the following morning with a jury which

included, amongst the twelve good men and true, some well known Deal

names. The Foreman was Mr F. Roberts and there were two near neighbours:

Mr W. Hunnisett the Linen Draper in the High Street and Mr E. Inkpen the

Coal Merchant of 3 Market Street. The Brewers were represented by Messrs

A. Morton and B. Turner.

Mary Jane Browning stated that she lived at the

"Druid's Arms." She then identified the body, just viewed by the Jury, as

that of her husband William Browning, licensed Victualler, and went on

to tell the melancholy story of the previous afternoon. He had, she

said, lived at the Druid's Arms since 1869. His only trouble was that

they were leaving the house because they were unable to pay their way

since her husband had broken his leg and could not take on beach work.

'He was not given to worrying about things until the last two years,' she

said, but she knew that he did not really want to give up the business.

She thought that he was so worried about leaving that it had preyed on

his mind.

Mrs Browning explained how she had left her husband sitting by

the kitchen fire, but when she returned he was not there. She took a

lighted candle and went upstairs to look for him, thinking that he had

decided, after all, to go to bed, although he had not told her as he

usually did. She looked in at the private closet, but he was not there,

so she opened the back door and called to him. There was

no answer and she thought that, having seemed so drowsy, he might have

fallen asleep in the public closet in the yard. She then opened the door

of the yard closet and saw her husband's body hanging from a beam. She

added that she remembered calling for Mr Wraight, but had no clear

memory of anything else at that time.

Mr Wraight went at once and cut down the body, saying that he thought

there was still some life in it. In his evidence Mr Wraight said that,

when he cut down the body there was still life in it and he carried it

into the kitchen asking Mrs Browning to send for a doctor, but one could

not be found for some time and when the doctor did arrive Mr Browning

was dead.

'I quite thought that I was going to restore him,' said Mr Wraight. 'The

string I cut from the body was no thicker than a penholder and he

breathed for about half a minute afterwards.' Mr Wraight stated that the

deceased's feet were about four inches clear of the ground. After cutting him down the witness said that he blew into his mouth to get the

lungs to work and kept rubbing at him, so as to get the breath in. He

had always found this the best thing to do, but no one came to assist

him. The Coroner said 'You acted very promptly, but I doubt if that is

the most approved method which is to let them lie on their back and work

the arms gradually up and down'. (These days Mr Wraight's method would

have been praised.) Mr Wraight rejoined with 'I always thought that

Christians were the same as dumb

animals and that is the best way to restore them. I could not get a

doctor so I doctored him as well as I could myself, but I saw no sign of

life after, except a gasp

or two'.

Representing Thompson's the Brewer, Mr Turner said that he would

like to state that the Browings were leaving the house at their own

request. The hope for a

tobacconist's shop was then mentioned: he had told them that, if they

wished to leave they could do so, but it was not necessary to

serve them with notice. Several months later the Brownings informed him

that they had found a place and would remove the best part of the

furniture and leave the other for valuation. Thompson's had found

another tenant and the change was to have taken place that day. The

deceased owed no money and Mr Turner made it very clear that the

Brownings had never had pressure placed upon them to leave. It was of

their own accord and at their own request. Dr Hardman (Coroner) asked if the Browmings were 'getting past the proper management of the house',

to which Mr Turner replied 'They could manage the house all right, but

people seldom come in to see old people'. 'Was business falling of?'

asked Dr Hardman. 'It was about the same as the last few years, but they

paid the firm very regularly,' said Mr Turner.

In summing up the Coroner placed some emphasis on how 'satisfactory' it

had been to have the representative of Messrs Thompson's present and to

know that - as it was supposed - there had been no harsh action from the

firm to the tenants. They were leaving of their own accord. He added

that it was probably reasonable to suppose that the breaking or old

associations might, to some extent, have weighed upon the mind or Mr

Browning, also parting from a home where he had lived for over thirty

years could have had a depressing effect. He said that, if the Jury

coupled these thoughts with the evidence given by the widow he felt that

they would have no difficulty in coming to the conclusion as to the

state or deceased's mind at the time he took his life. A verdict was

returned 'at once' on suicide during temporary insanity.

The local newspaper carried the notice or Mr Browning's death with

nothing more than: 'BROWNING October 15th, at the Druid's Arms, Market

Street, Deal, William Browning, aged 67 years'.

Some time later the Druid's Arms became the Druid's Supper Rooms, under

the management of a Mr Catt who later founded Catt's Restaurant which

was so popular in Deal until the 1970s.

Editor's Note

The licensing Act of 1872 restricted pub opening hours in England. In

towns, pubs could now only stay open from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. It was an

unpopular measure. A further licensing Act in 1902, aimed at reducing

Britain's pubs by one third, did away with many undesirable (or only

marginally profitable) houses. Perhaps the "Druid's Arms" was in this

category and it may have been the cause of the landlord's worries.

|