|

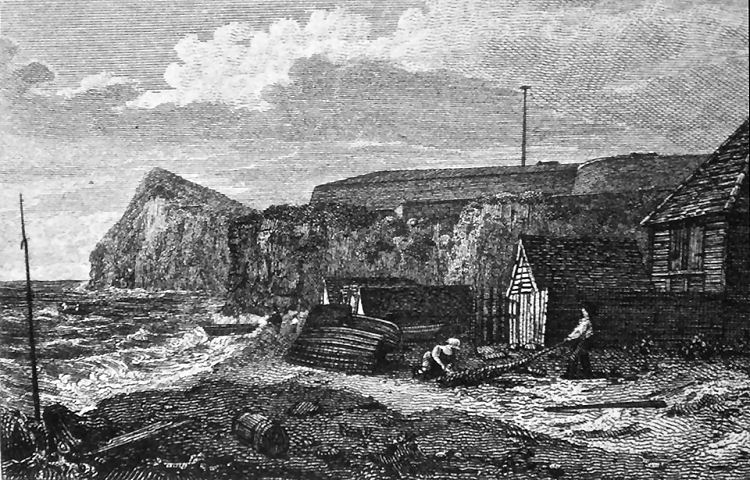

Bottom of Shakespeare Cliff/Beach Street

Dover

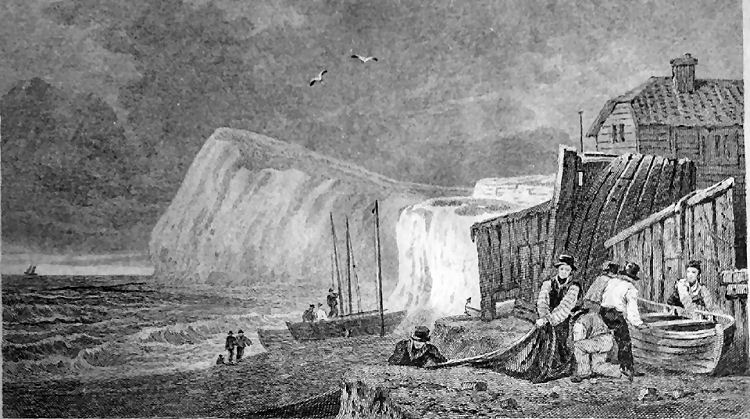

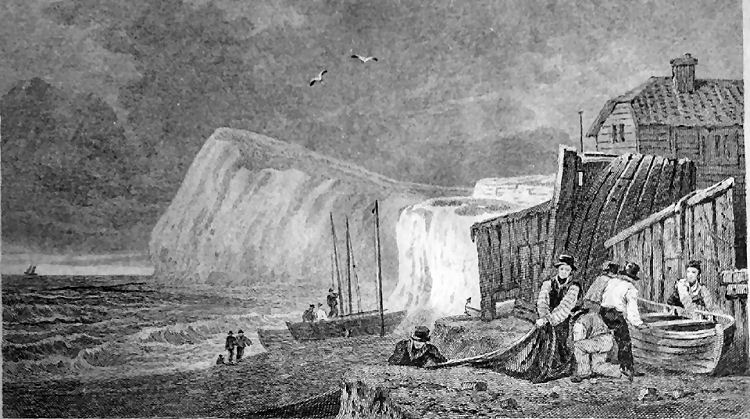

Samuel Austin (1796 - 1834)

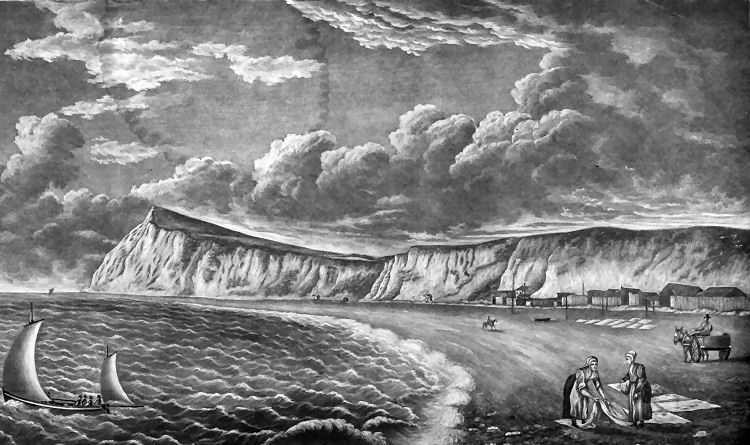

"Shakespeare's Cliff, Dover, with Luggers on the Beach on" |

Above print showing fishing boats, and perhaps the "Mulberry Tree."

Engraved by Henry Adlard from an original study by Henry Gastineau 1831. |

Above painting obviously taken from above print. The title says:-

"Shakespeare's Cliff. School copy from Print, J. W. H. 1832." |

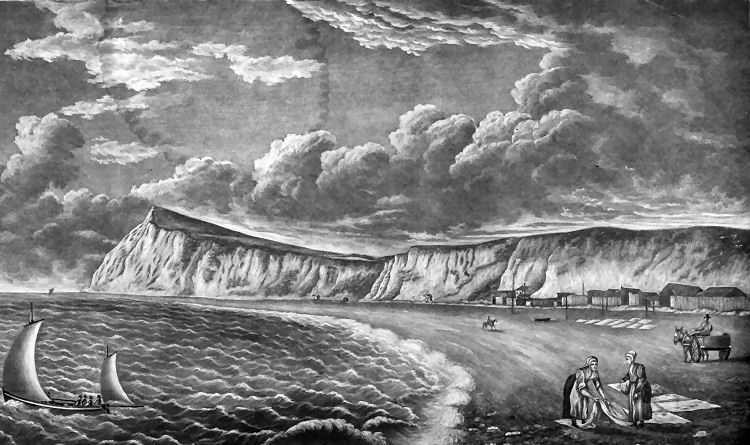

Above painting 1812, showing the "Mulberry Tree" and Shakespeare Cliff.

Title says:- "1812, Mulberry Tree Inn and beach where now stands ?????

Station." I can't make out the artists signature or date. |

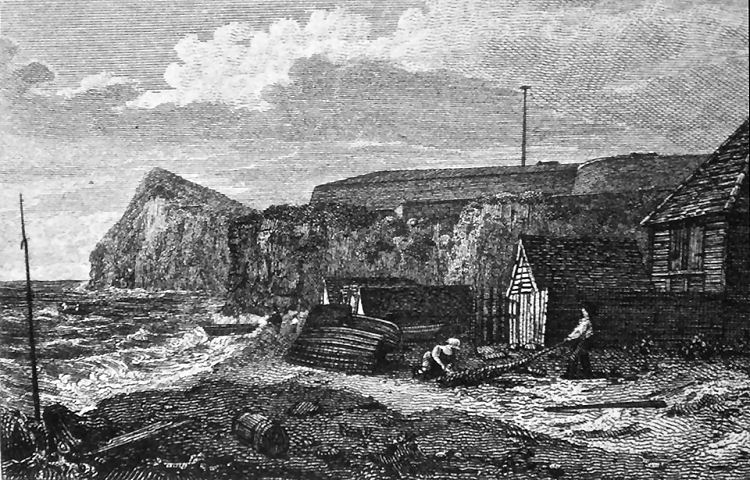

Above print by W. Doble, published 1877. Titled "Shakespeare's Cliff

& Archcliff Fort." |

Above print showing the Shakespeare beach before the railway and

Becker's Steps. I believe the "Mulberry Tree" is just above the horse in

the print, date unknown. |

Above photo from Shakespeare Cliff, painted by William Daniell in 1829.

May just show the Mulberry Tree under the cliffs. |

|

Built at the extremity of the street under Arch Cliff, it was well

established in 1807 but its site had to be surrendered to the South

Eastern Railway when they arrived in 1843.

|

Shakespeare Cliff, Dover, 1849 Artist Clarkson Stanfield Date 1862

A composition in which the artist has incorporated recognisable

features at Dover, about 1849, with imaginary narrative. The painting

falls into two parts with a brig shown on the left amidst dark clouds

and a stormy sea. It is flying the red ensign upside down to indicate

that it is in distress. A boat is being launched from the beach to go to

its assistance. On the right preparatory stages for the construction of

a pier are underway. The artist has carefully delineated the various

processes involved at the building site such as a hoist, ladders and

blocks of stone together with several manual workers in red caps at the

site. They do not appear to be aware of the ship in trouble at sea and

this reinforces the appearance of two distinct narratives. Only the man,

woman and child in the middle distance look directly at the ship from

the raised quay.

The view is taken from the position of the modern Admiralty Pier, with

the sea on the left. Shakespeare's Cliff rises to dominate the skyline

in the distance with the two tunnels of the London-Dover railway visible

at its base, following the arrival of the South- Eastern Railway via

Folkestone in 1844. On the right is the Pilot's Watchtower, which was

constructed in 1847 and demolished by 1910. This structure was used to

house the pilots who were able to keep a continuous look-out for passing

vessels in need of their services to guide them safely into port. In

1846 there had been a recommendation that Dover become a harbour of

refuge 'capable of receiving any class of vessels under all

circumstances of the wind and tide'. The following year, probably the

year of the preliminary sketches for this painting, work began on the

western arm of the harbour commissioned by the Admiralty. The painting

can be seen as a glorification of industrial progress, and Dover as the

place at which England advances towards the continent of Europe, yet

equally defines its own boundary. The white cliffs bear a symbolic and

historical significance making Dover a locus of identity for the

sovereignty of the nation. However the inclusion of the contrived scene

on the left invites a less confident reading.

After Turner, Stanfield was considered the greatest British marine

painter of his day. He started his working life at sea, but his talent

for sketching attracted attention and from 1816 to 1834 he rose to

become the leading theatrical scene painter of his day. At the same time

his growing success as an easel painter of marine and coastal views

built him a success which enabled him to give up the stage and from 1835

he became an Academician of powerful influence. The painting is signed

'C Stanfield RA 1862' bottom left and was exhibited at the Royal Academy

in 1863.

|

|

From the Dover Telegraph and Cinque Ports General

Advertiser, Saturday 3 June, 1837. Price 7d.

SHOCKING OCCURRENCE

The inhabitants were thrown into a state of agitation an alarm on

Monday afternoon, by a fatal occurrence which has since proved a cause

of affliction and consternation to several respectable families in the

town. Soon after noon on that day, the body of a female was discovered,

quite dead, at he base of Shakespeare's Cliff; and from the dreadful

lacerations and disfigurement it presented, there could be no doubt of

the fact that the unfortunate lady had fallen from the 'dread summit of

chalky bourn,' the height of which above the spot where the body was

found, is at least three hundred and fifty feet. At about a hundred feet

from the base, a slipper was distinctly to be observed adhering to the

chalk, from which it may be inferred that her feet struck the face of

the cliff in the decent; but as no one saw her fall, the cause or manner

of her precipitation from the summit is unknown. The body being removed

to the "Mulberry Tree" public house, on the east side of the cliff, it

was discovered by her name written inside the remaining shoe, to be that

of Mrs. Catherine Elwin, wife of Mr. Elwin, grocer, in St. James's

Street, and was afterwards further identified by the dress she wore; but

from the disfigurement before remarked the features could not be

recognised by her relative who attended. Mrs. Elwin, it was stated, had

left home after breakfast, intending to take a walk previous to

proceeding to dine with her sister, Mrs. Birch, on the Military Road. A

lady was seen on the cliff about half past ten, by two of the coast

guard who were in a boat at sea; and she was also seen by persons from

the heights; but none of hem witnessed the fatal occurrence.

The place where the body was found being just without the limits of

Dover, the circumstances were reported to the County Coroner, and on

Wednesday an inquest was held at the "Mulberry Tree," before T. T.

Delasaux, Esq. and a jury from the parish of Hougham; Mr. R. Marsh, of

Farthingloe, foreman. The first witness examined was Richard Richards, a

fisherman. He stated that between twelve and one o'clock on Monday,

while walking on the low water rocks, he saw a lady's bonnet between him

and the cliff; and on going to pick it up, he discovered the body of the

deceased, in the situation above described. Life was entirely extinct. He body was not cold; but that might be accounted for by the heat of the

sun against the cliff. Witness called another man, named Mallett, from

the water rocks, who went for assistance; and others of the preventative

service coming up, they conveyed the body to the "Mulberry Tree."

Elizabeth Beer, servant to Mrs. Elwin, underwent a longer

examination. She saw the deceased at half past seven, on Monday morning,

when she took breakfast, in bed, as was her custom. She saw her mistress

again at half past eight, for the last time alive. There was nothing

different in her manner from her usual conduct; and witness understood

that she went out, intending to dine with her sister, Mrs. Birch, in the

Military Road - Believed there was a road from Shakespeare's cliff to

the Military Road. Her master, who dined at home, knew his wife was gone

out to dinner. About half past two he enquired what dress her mistress

wore when she went out? Witness could not tell; but ascertained from

what was taken from the room where she had dressed. She then heard of

the fatal event - thinks it was communicated to her master by Mrs.

Bradshaw. Mr. Elwin appeared agitated; and afterwards speaking of the

circumstance, he said it was a most extraordinary thing. Does not think

he left the house that evening, or that he had seen the body. He asked

if her mistress had said anything to her on going out? to which he

answered no. She did not see her go out. In answer to questions by the

Foreman and Jurors, witness said the deceased, who had six children,

attended correctly to the domestic and household affairs. She had been

unwell some time ago; but otherwise there was nothing particular in her

manner. she lived very comfortably with her husband. Witness did not

think that any couple could be happier than they were.

Mr. Thomas Birch, brother-in-law of the deceased, deposed that he had

known her from infancy. Her temper was extremely mild and placid; and

the fatal event was a blow which had stunned the whole family. She was

in the frequent habit of spending the day at his house; and the

impression on their minds was, that hse had taken a walk previous to her

intending going there on Monday; and his belief was, that she had met

her death accidentally. The effect of the fatal event was

extraordinarily severe on her husband, who seemed almost bereft of his

senses.

There being no other evidence, the coroner briefly remarked on that

adduced, observing that there was considerable mystery attached to the

melancholy circumstance; and nothing, perhaps, to warrant there giving

a verdict of accidental death. Still, on the other hand, they had

evidence that no derangement existed in the mind of the deceased. If

they felt justified in the performance of their duty to say accidental

death, it would become his duty to record it; but under all

circumstances, a general verdict of found dead, would be more advisable.

The jury then returned their verdict accordingly.

Found Dead.

|

|

From the Dover Telegraph, 14 July, 1838 p. 4 & 5

John HARVEY and wife

Elizabeth, of Dover: compensation case for their interest in a lease of

garden and premises known as the 'Mulberry Tree' public house at the

foot of Shakespeare's Cliff, held under the Lord of the Manor of

Sibertone for 21 years from Jan. 1835 at 20 shillings per year.

The site

now included in a schedule of lands in the Act of Parliament now

required by the Railway Co. for continuance of the line from the opening

of the tunnels to the town of Dover. Offer by the Company of £850 but

they demanded £2340. Three and half columns report of the case.

Witnesses re. Harvey's business and market garden. Jury decided on

£878.4s.

|

Although the above two pictures do not show the actually "Mulberry Tree",

I believe they show the relative location of it.

A "Mulberry Tree" was said to occupy ground at the entrance to

Shakespeare tunnel itself, complete with tea gardens, at the bottom of the zig-zag winding footpath which descended the

cliff. Apparently whilst the tunnellers were still engaged on that project.

Old prints do show a building in that vicinity. I know not if that is the

same. Many of those tunnellers were said to lodge in Archcliffe Square but I

have also read that not a room in the whole pier district was left unused.

I have also, just heard of another possible pub at a location down by the

sea, perhaps around the Lydden Spout area at the base of Shakespeare Cliffe.

See the "Shakespeare Head".

The Dover Express has a series "Way we were". In a recent edition, May

26th 2011, Terry Sutton has written about shipbuilder William King. The

feature includes mention of the "Mulberry Tree Inn." Extracts from that

write-up are as follows:-

[...] In the last ten years of the 18th century enterprising shipbuilder

William King was so popular he was eventually elected mayor of Dover. His

shipbuilding yard was on the harbour's southern beach, within near sight of

Townsend Battery and the pilot's lookout station near Cheeseman's Head.

[...] After their daily toil William King could often be found with his

workers sharing gossip with other shipwrights, hovellers and the occasional

smuggler at the "Mulberry Tree Inn," not far from Shakespeare Cliff. There

was much patriotic talk among the drinkers at the "Mulberry Tree" -- so much

that some of the more agile customers volunteered to join the ranks of the

Dover Volunteers, who were being armed to ward off a French invasion.

|

From "The Life and Times of Charles Norris Becker.

Charles Norris Becker was a town crier of Dover and he mentions the

following on a page of his book:-

PETER BECKER GRANDSIRE.

My grandfather, Peter Becker, was, in 1790, First Lieutenant in the

old Volunteers, under King George Ill. I have his indenture. Then he

kept a public house, "The Mulberry Tree" Inn, at the entrance of

Shakespeare's Cliff Tunnel, where a lot of smuggling was carried on. The

steps leading from the top of the Cliff were made by his instructions,

and were called "Peter Becker's Steps." Then he was proprietor of the

old Oil Mills as a corn store, which were burnt down but were not

insured. On November 8th, 1910, my sister Jane died; and on December

21st in the same year my adopted son, Arthur Minto, died at Lahour, East

India. My brother and his two lovely daughters are still at 154,

Snargate Street, in the greengrocery line; and your humble servant is

still in the land of the living at 130, Buckland Avenue, Dover.

Before closing my narrative, I should like to thank Sir William

Crundall and all the Town Councillors for the kindness I have received

during my term of office as Town Crier.

Dated this First Day of January, 1912.

CHARLES NORRIS BECKER.

|

Above photo showing Shakespeare Cliff 1950, and I believe the rough area

that the "Mulberry Tree" would have been situated. |

LICENSEE LIST

BECKER Peter 1790+

HARVEY John 1838-43

GRAVENER Mr 1843

|