|

Kentish Chronicle, Saturday 8 October 1864.

DREADFUL EXPLOSION OF GUNPOWDER AT ERITH.

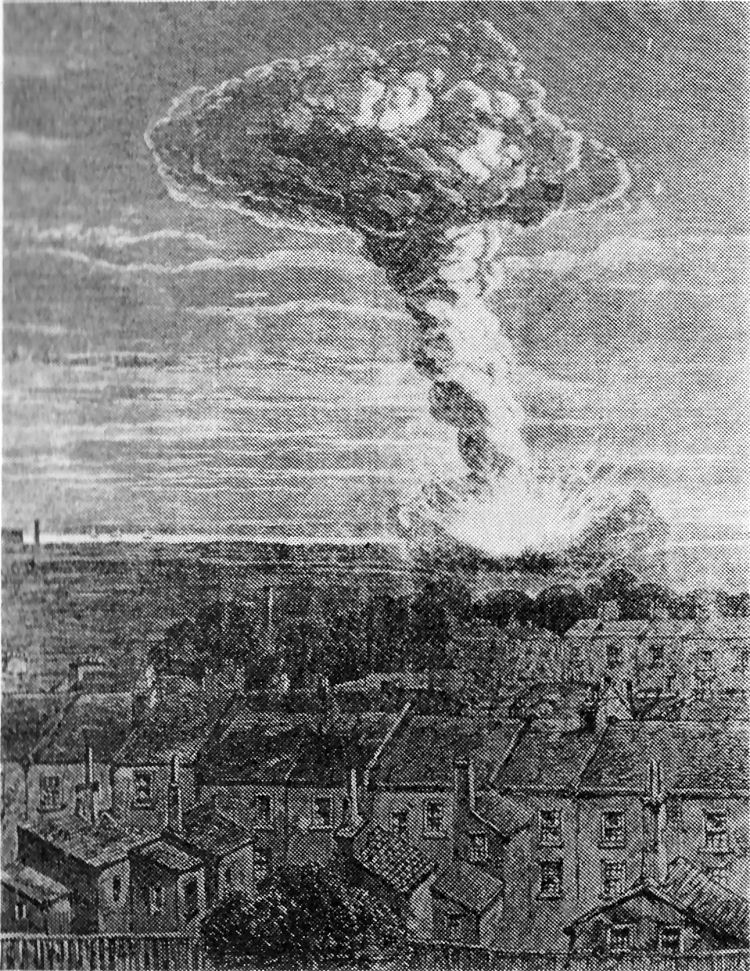

Above engraving showing the view of the explosion, as seen from

Burrage Road, Plumstead, by Captain Pasley, R.E.

On Saturday morning, at twenty minutes before seven, the inhabitants of

the whole metropolis, with scarcely an exception, were startled by a

singular, sadden, and inexplicable phenomenon. Those who were asleep

were brusquely awakened by a strange rattling of their windows, as if

the sashes had been struck by a violent gust of wind, which threatened

to blow them in. To spring out of bed and run to see what was the matter

was almost a matter of instinct, and it may be confidently affirmed that

so many people were never before looking out of their chamber windows at

a given moment. As it appeared, however, that there was no wind at all

to speak of, the conviction at once settled down on the public mind that

there had been an earthquake, and that one of by no means a trifling

character. The earthquake theory however, was not left long without

question; for those who were up and in the open air say that they had

heard the shaking of the houses preceded by three or four distinct

reports; and a favourite suggestion, therefore, was that the gasometers

at one or other of the great companies’ works had exploded. After a

short time a new hypothesis was started, namely, that an accident had

happened to some powder magazine at Woolwich. This was getting very near

the truth, and at lost the real fact became known. There had really been

an earthquake, but it was one that had been caused by the blowing up of

two great stores at a place on the Erith marshes called Low Wood,

situated between Plumstead and Erith, on the banks of the Thames. At

this spot, about a mile or a mile and a quarter from the Belvedere

Station of the North Kent Railway, and between the latter and Erith

Church, and closely abutting on the banks of the river, at the end of

Erith Reach, were two large magazines, the property of Messrs. Hall and

Son, of the Dartford Powder Mills, and of Lombard-street, and the Low

Moor Company, of Tranmere, Lancashire, for which Messrs. Filbey and Co.,

of 63, Fenchurch-street, are the agents. The plot of land on which those

magazines stood, and which is surrounded by ditches, to render them

isolated, is possibly in extent about twenty-five acres. The magazine

belonging to Messrs. Hall and Son was the more easterly one of the two,

that belonging to the company standing on the north-western side of it,

close up to the embankment of the river, the distance between the two

magazines possibly being between fifty and sixty yards. The only other

buildings in anything like close proximity were the residences of the

foremen or managers of the works and their families, and one or two

cottages for employees. Those belonging to Messrs. Hall and Son were to

the south-east of their magazine, and here in the larger house resided

Mr. Silver, the manager, whilst on the extreme west was the house of Mr.

Raynor, the foreman, and his family.

It appears that two barges left the powder mills of Messrs. Hall and

Son, at Dartford, on Friday night, and proceeded up the river, both

completely laden with casks of gunpowder, for the purpose of depositing

them in the magazine, at first supposed. They were then known to have

each two men and a boy on board, but whether there were any others, as

it is feared there were, has not been ascertained, although several who

were known to be associated with the bargemen are missing.

It is believed that the explosion first took place on board one of the

barges; and it is suggested—though there is not the smallest particle of

proof of it—that it might have been caused by a spark falling from a

pipe, which one of the bargemen might have been smoking. It is, however,

said that Mrs. Raynor, who was extricated from the ruins of her house

alive, on being asked where her husband was, answered faintly, "Oh, I

know he must be killed. He came to my bedside and told me to get up, and

I saw him blown through the wall of the house when the explosion took

place." If this is true, it would appear that the origin of the disaster

was not on board the barges, but both they and the two magazines were

blown to pieces. The quantity of powder which exploded has been

immensely exaggerated by public rumour. It was stated that there were

not less than 30,000 barrels in the magazines, each barrel containing

from 80lb. to 100lb.; but Messrs. Hall write to say that they had only

700 barrels in their stock, besides 200 which were in the barge. The

quantity in the other magazine has not been stated.

Whatever the quantity might have been, the results of the explosion were

terrible. Not only were the magazines, strongly built as they were,

razed to the ground—nothing whatever being left but their

foundations—but the very earth itself, for the space of hundreds of

yards, was turned up in huge masses or blocks of a ton weight and

upwards in all directions. Mr. Silver was writing in his little office,

and was nearly buried amid the falling walls, floors, and ceiling of the

house, but he extricated himself, and was comparatively unhurt. A nephew

and niece, who lived with him, were both in the house; they were much

injured, and the niece was not expected to recover, having been partly

disembowelled. The debris lay scattered for many hundred yards in every

direction, and there were to be seen heavy beams of timber, some

weighing over half a ton, in the adjoining fields. A large portion of

the Belvedere station, upwards of a mile distant, was carried away; and

at the moment of the explosion, the bricks of a new building in course

of erection at the station were scattered over the line. In the

districts of Erith, Belvedere, and Plumstead, not only were the windows,

but the sashes, and even the shutters blown out; and there was scarcely

a house that had not suffered more or less. Woolwich also suffered

immensely; the Barrack windows on the common were smashed in every

direction. So great was the shock that it was at first thought that some

dreadful disaster had happened at the Arsenal, and the greatest alarm

was felt in the town and the greatest alarm was felt in the town in

consequence, It was not until portions of Messrs. Hall's books and

papers were seen floating in the air that the exact truth was

ascertained. A man named James Girnes, who was at work just off the spot

where the explosion took place, ballast heaving, states that he happened

to look towards the magazine, and at the moment he saw something bright

on board one of the barges. He said to his mate, "Why there's a flash of

lightning," and almost before he got the words out of his mouth, there

was an explosion. He was blown up into the air out of the lighter at

least thirty yards (according to his own words), and fell down on the

dock, from which he rolled into the river and swam ashore. As he was

doing so a large piece of timber struck him on the hip and injured him

so severely that he could scarcely reach the shore and crawl on to the

bank, where he lay for some time in great agony until he was fortunately

discovered and removed.

The shock is thus described by a watchman at Gravesend:- "I was on the

pier," he said, "when I suddenly lost my balance, and almost

instantaneously I heard an awful explosion. On turning round I saw, as

it were a pillar of fire rising to the clouds, which it appeared to

strike, and then spread out like a huge fan, presenting a most beautiful

and grand spectacle."

Sergeant Cox, of the police division stationed at Erith gives the

following narrative of the circumstances:- He was getting up about a

quarter to seven when he heard the explosion. He ran out and found all

the back windows were broken, the sashes as well as the glasses. He

looked in the direction from whence the sound proceeded, and imagining

from the smoke that one of the magazines had exploded, he proceeded to

the scene of the disaster, procuring assistance by the way, Mr. Churton,

and Mr. Tipple, two medical gentlemen of the vicinity, were on the spot

almost as soon as the police, and, with Mr. Matthewson and other

surgeons, did all that was possible for the sufferers. On arriving at

the scene of the disaster, having literally picked his way through the

heaps of rubbish and masses of stones and brick that had been strewn

about by the explosion, Sergeant Cox went to the place which, alas! had

been occupied by Mr. George Raynor's cottage, the manager of Messrs.

Hall and Son’s magazine, and there in the garden found the body of the

unfortunate man lying on the ground. He was dressed, but had not got on

the usual slippers that are worn in the magazine. He was much cut about

the face, as if by splinters, and the back part of the head, over the

left ear, was cut open, the brain protruding. He was quite dead.

Sergeant Cox next saw Mrs. Rebecca Wright, who was removed as noon as

possible, under the care of the medical men. A son of Raynor, named

Oliver, was next discovered. His head was smashed in a fearful manner,

and death must have been quite instantaneous. There was no indication,

either upon father or son, that concussion had caused death; it must

have been from the splinters or brinks hurled in all directions by the

fearful explosion. Elizabeth Wright, aged thirteen, a daughter of the

poor woman previously mentioned, was next found, and she was carefully

removed to Guy's Hospital in the train, but died a few minutes after her

admission. She had sustained a compound fracture of the skull, a

fracture of the left thigh, and was severely burnt on the chest and

upper extremity of the body. The bodies of Raynor and his son were

removed to the "Belvedere Hotel," and placed in a shed to await the

coroner’s inquest, and shortly after, the body of a man, apparently

about sixty years of age, not known, was found in the mud of the river,

and he was also conveyed to the same place. Among the others found,

those whose names we append were conveyed to Guy's Hospital, and it is

needless to say they received every attention from Mr. Sidney Turner and

the other officials:- Mary Yorke, thirty-eight, fracture of thigh;

Lennie Yorke, seven, contused arm and leg, with burns; Dinah York, six,

wounds on face, back, and legs; Elizabeth Osbourne, seven, wounds on

face and hands; Edward Singleton, twenty-four, fracture of arm and

burns; Jane Eves, thirty-eight, fracture of skull—very dangerous (since

dead).

In addition to this list we have to give a further number, comprising

George Smith, William Mildred, William Edwards (who was thrown a

distance of upwards of thirty yards from where he was standing); William

Johnson, who was much hurt about the head and shoulders; and George

Hubbard, who was found lying outside at the back of one of the cottages.

Two children, named Alfred Raynor, aged 12, and William Yorke, aged 11,

were taken charge of by Captain M'Killop, who resides at Belvedere. The

first named was found on the first floor of the cottage, part of which

yet remains standing. The poor little fellow was covered with plaster

and dust from the ceiling, but irrespective of the fright did not

sustain any injury. Two younger children belonging to Mrs. Wright are in

the care of Mrs. Price, of Lessness-heath, and that completes the list

of those who have been found. It is most lamentable to have to record

that the bodies of two of the men who worked with Raynor have not yet

been recovered. Their names are Yorke and Wright.

A very short time elapsed after the catastrophe before an important

discovery was made. It was found that the embankment of the river had

been broken to the extent of between 170 and 180 feet, and although

fortunately at the time it was low tide, it was felt that unless most

energetic exertions were used, the river would overflow and cause the

most serious destruction. Some three or four hundred men from the main

drainage works at Crossness Point were speedily on the spot with shovel

and pick, and by great exertion, aided by relays of the Engineers,

Marines, and Artillery, to the number in the aggregate of nearly 2,000

men, and the use of sandbags supplied from the military stores, they

succeeded in keeping out the water, although about one o'clock, when the

tide was at its height, the water was found to be making its way through

the bank, and the greatest apprehensions were excited. Fresh detachments

of troops, however, arrived, and Mr. Webster’s navvies, by redoubled

exertions, succeeded in making the bank temporarily secure. By this

time, the locality of the disaster having become generally known, the

South Eastern Company brought down by every train during the afternoon

hundreds—one might almost say thousands—of people.

On Sunday it was found that the precautions which had been taken to

prevent the inundation of Erith would prove ineffectual. It was found

the new embankment had begun to give way. Five hundred of the Royal

Horse Artillery and a body of sappers and miners were sent from tho

Arsenal, and sandbags and entrenching tools, picks, rammers, shovels,

&c., were forwarded by rail and artillery wagons by Captain Gordon, of

the Royal Horse Artillery, and principal engineer of the arsenal. Upon

arriving at the scene

of the threatened inundation it was found that not a moment was to be

lost. The 150 navvies had been hard at work during the night, and they

were completely worn out. They were immediately dismissed from their

labours, and the troops took their place. The artillerymen stripped to

their work, and went at it with a will. Numbers were told off to fill

the sand bags, of which several thousands had been brought down from the

arsenal, which was fortunately so near, and the rest, with the sappers,

began the labour of constructing a new embankment. The whole area

occupied until Saturday morning by the powder mills and other buildings

of Messrs. Hall at once assumed the aspect of a camp.

By slow degrees the tide rose, and its progress was regarded with no

little anxiety by the officers in command of the works, but owing to the

unwearied exertions of the men under them the barrier advanced in

proportion. It steadily increased it height and width, and when at three

o’clock the water rose to its greatest height, the pressure, though

rendered immense by the wind, which blew with extraordinary force right

up the river, was met with a resistance that proved effectual, and the

danger was pronounced to be over. To show how real and imminent the

danger had been, it is only necessary to state that all the efforts of

the military had only been efficient to raise the barrier twelve inches

above the level to which the river reached at the hour in question. At

half-past four the trumpet sounded, and the troops, amidst loud cheers,

threw by their tools, having triumphantly accomplished their work.

The number of excursionists to the spot was extraordinary. Some 30,000

went down during the day from London-bridge station alone, and it may

safely be estimated that from other stations and by other routes at

least four times that number found their way to the spot. The roadway on

one part was so completely blocked up that the military, on their return

at five o'clock in the evening, were brought to a dead stop, which was

only put end to by their charging forward and tumbling the luckless

civilians into the fields and ditches at either side—an operation which

was, strange to say, provocative of much merriment to all concerned.

Latest Particulars.

Terrible and destructive as true the explosion the accounts which bare

been published, obtained in the confusion and excitement, are,

fortunately, much exaggerated, both as to the amount of property

destroyed and the number of persona killed and injured. Instead of

million pounds-worth of property being destroyed, as at first supposed,

a quarter of a million is more near the truth, while the deaths may be

set down at about twelve in number, instead of forty, as at first

stated, and the persons more or lees injured are about twenty the most

serious cases, nine in number, having been taken to Guy’s Hospital,

those suffering from bruises only having been accommodated in the

neighbourhood. The town of Erith, at first reported to have been almost

destroyed, has escaped any serious injury, which may be accounted for by

a strong wind blowing towards the metropolis, and it was, no doubt,

owing to this circumstance that the shock of the explosion was felt so

severely throughout London and its suburbs. The works destroyed were not

manufacturing powder mills, but simply a powder store or depot, and the

number of persons employed there were but few. It is owing to this that

the loss of life has been comparatively small.

There can be no exaggeration, however, as to the scene of destination

and desolation presented on the spot where the magazines once stood.

With the exceptica or a portion of the side wall of the manager's house,

not a vestige of the numerous buildings is left standing. For at least a

mile around the marshes are covered with bricks and timber, a great

portion of the latter being much charred, as if by fire.

The number of persons who visited the scene of destruction on Sunday was

enormous, and the police estimate that at least 100,000 persons were

present during the day.

Upon inquiry at Guy’s Hospital on Sunday night at nine o'clock, it

appears that of the nine persons brought in there two are dead; one,

Elizabeth Wright, aged thirteen, who died almost immediately after

admission on Saturday morning; and James Eves, who died on Sunday

afternoon at three o'clock. A third sufferer, named Eliza Osborne, aged

eight years, presents a pitiable spectacle, her face, head, and hands

being frightfully lacerated. She was not expected to survive the night.

The other six are all going on favourably, and no fatal result is

apprehended in those cases.

The scene presented on Sunday at the London-bridge station of the North

Kent line was one that almost baffles description. The railway

authorities, in anticipating there would be large extra traffic

consequent upon the desire of the public to witness the scene of the

explosion, had made arrangements for the running of several trains, in

addition to those usually running on the Sunday, but their arrangements;

fell far short of what was required, and the result was, especially in

the after-part of the day, considerable confusion and disappointment. On

the re-opening of the station at one o'clock the rush of people into the

booking offices was tremendous, and the platforms, both on the high and

low level, speedily became filled with a dense multitude of people

impatient for conveyance either to Belvedere or Erith stations. From one

o'clock until three the trains departed in rapid succession, no less

than ten trains besides the two ordinary ones having been despatched

between those hours, but still there was no perceptible diminution in

the crowds on the platform. Soon after three o'clock a telegraph arrived

at London-bridge requesting that no more trains should be despatched

until the ordinary train at four o'clock. As the line was completely

blocked up, telegraphs were at once sent down the line to the effect

that on no account was a train to leave a station before the station

master had received a telegram that the trains in front had left the

station in advance. At four o'clock there could not have been less than

5,000 persons crowded together on the London platform of the low level

station, and at this moment an up-train ran into the station on the off

side. It had hardly stopped to enable the passengers to alight, when a

terrible rush was made from the opposite platform and across the line,

carriages were scaled in all directions, and the people made their way

in through the windows before the up passengers had vacated their

seats. As may be supposed, the greatest possible confusion ensued, as

not one-tenth part of the people could obtain admission into the

carriages although as many as eighteen and twenty crowded into one

compartment-intended to accommodate only ten persons. Similar scenes

were also taking place at Charing-cross station, though not to so great

an extent.

Great praise is due to the railway guards, porters, and others on duty

for the manner in which they performed the arduous duties falling upon

them so unexpectedly. Up to ten o'clock but two accidents had been

reported; one being the catching fire of one of the carriages of the

train leaving London-bridge at three o'clock, from the friction on the

wheels, compelling the train to return to the station for the carriage

to be taken off, during which time a lady had her foot severely burnt,

and the other that of a lady having her leg broken in the struggle to

get into a carriage at the Plumstead station.

At eleven o'clock the trains were coming in rapidly to London-bridge,

the passengers by which reported that a large number of persons were

still waiting down the line.

A large number of persona were taken down to Erith per steamboat, and

the road from Woolwich to Belvedere was crowded with vehicles and

pedestrians.

A Woolwich correspondent writes:— "Sunday, 9 p.m.— The streets of

Woolwich are at this hour crowded by thousands of persons who have

visited Belvedere, and have been totally unable to obtain railway

accommodation for their return. Throughout the day the entire line of

route from London to Erith had presented a spectacle resembling that of

the road to Epsom on a 'Derby day.' Carriages of every description, from

the barouche to the costermonger's barrow, have passed through Woolwich

in a continuous stream, and the pressure on the locomotive department of

the South Eastern Railway has been such that it was impossible to

accommodate the traffic, although numerous extra trains were in

requisition. The rush this evening at the Belvedere, Erith, and

Plumstead stations of the North Kent line by passengers anxious to

return home baffles description, and several accidents have occurred.

At the time of the explosion a complete shower of papers, consisting of

accounts and documents relating to the powder factories, fell over the

area of Woolwich, Plumstead, and Charlton, and an oil portrait of Lord

Nelson, partially blackened by powder, was picked up at Plumstead

railway bridge. The whole of the available police force from the A, R,

and M divisions were on duty at the scene of the catastrophe during the

day. And from the exertions made by the military, and the labourers

employed by Messrs. Webster, the contractors for the outfall sewage

works, the river wall is believed to be perfectly secure, and the whole

of the military returned to barracks on Sunday night.

An immense number of details, illustrating the damage which was done by

the explosion, have been collected by the industry of the reporters. The

following will serve as a few specimens:— In the neighbourhood of

Newington, Camberwell, Dulwich, Peckham, Sydenham, &c., the shock was

felt with tremendous violence. In the Walworth-road, at Sutherland

Chapel, a large number of the windows were shivered, and at a shop in

the same thoroughfare the shutters were hurled into the roadway, the

plate-glass front at the same time splitting in all directions. At a

large building in the Walworth-road the brickwork was found to be split

up, and some men going to work describe the shock as something terrible,

lasting several minutes, as though the ground upheaved. In

Francis-street, Newington, a gentleman describes the effect as truly

alarming, the doors of his house being dashed open, locks and bolts

being torn away. At other dwellings the result was the same.

The effect of the explosion was felt at the Crystal Palace and

surrounding neighbourhoods indeed, at the Crystal Palace the oficials

rushed out in great terror, firmly believing that the great towers had

fallen, and they could scarcely credit their senses when they found that

the building stood intact. Even at Notting-hill the shock was so

severely felt that it is stated the two stained-glass windows in one of

the churches were blown out and smashed. At the house of Mr. Simkins,

tailor, of New Church-road, Southampton-street, Camberwell, two young

children belonging to a lodger were literally tilted out of bed, and the

building itself was much shaken. Mr. D. Smith, bootmaker, of

Edward-street, New Church-road. states that he was standing in his

passage, when he was seized with a sensation as if he was about to be

suffocated, and believed at the moment that the house was about to fall.

In the same neighbourhood, at the wood yard of Mr. H. Fielder, a large

stack of timber was thrown down, and a portion fell upon the roof of a

small house adjoining it and dashed it in. Fortunately, although several

persons were in the house, no one was injured, with the exception of a

little boy who was asleep in the top room, and was somewhat severely

bruised about the head and face.

At Blackheath the front of the premises of Mr. Tripp present a picture

such as would have been caused by a fire, or some violent explosion

within the building. Most of the houses from this part to Dartford are

also more or less injured. A solicitor, named Russell, was shaving in

his dressing-room, and at the moment of the shock he suddenly found

himself on the floor. His wife was so frightened at the terrible shaking

of the house that she jumped out of bed and ran into into the garden in

her night-dress. The house was in so dangerous a condition that Mr.

Russell removed his family as soon as possible.

The shock of the explosion was distinctly felt at Guildford, a distance

of forty miles, as the crow flies, from Erith. There, as elsewhere, it

was at first attributed to an earthquake. It was also felt distinctly at

Cambridge and in the Isles of Ely, at a distance of sixty miles.

On Monday the scene of the calamity was visited by some 18,000 or 20,000

persons, who expressed their disappointment that there was so little to

be seen. But the explosion made too clean a sweep to leave anything as a

spectacle. From two little facts readers who have not seen the ruins may

gather some notion of the force of the explosion. In a field some 300

yards from the site of the stores lies a heavy beam, perhaps, twelve

feet in length by one and a half square. This has evidently pitched upon

its end, ploughed up a considerable space of ground, made a deep hole,

and then jerked itself four or five yards further. Again, the chain

cable of one of the barges, torn away from the anchor, and still

attached to the ring of the anchor-stock, is lying in the middle of a

ploughed field, at least 500 yards away. And such facts might be

multiplied by any one who takes the trouble.

It is to be feared that the list of victims mortally stricken is not yet

complete. One poor fellow named Grimes lies in dire strait at Erith,

with the lower portion of his back smashed in, and the accident happened

in this wise. He was on an empty barge belonging to the Trinity House,

midway in the channel, when the explosion took place. He was thrown

clear up from the deck, the tiller catching him and literally staving in

the base of the spine. Falling into the water he was seized by the hair

by one of his mates, who having been below escaped the force of the

shock, and who supported him until a waterman named Williams, plying a

few yards off, came alongside. This poor boatman had himself a portion

of his cheek cat away by some of the falling wreck, but though suffering

much he gallantly said he was not so bad but what he could help another,

and he managed to convey Grimes to the shore, where he lies in a

perfectly helpless condition.

Up to Monday the police continued to find portions of human frames about

the locality, and these have been put together as well as possible so as

to give some chance of identification. York and Wright were the names of

the men employed inside the magazines, and of these there is hardly a

chance of identification. The two barges were the Good Design, William

Jemmett, master, and Luke Barber; mate; and the Harriet, John Dadson,

master, and Daniel Wise, mate. A son of Dodson had come up from

Faversham on a short trip, and it is suggested—though in the absence of

any evidence the suggestion is almost a libel upon the poor lad’s

memory—that the boy was lighting a fire and so caused the explosion. At

any rate, a portion of a foot has been found, and pronounced by the

surgeons to be that of a child; so that there does not seem any reason

to doubt that the boy was killed at the same instant as his father. The

Harriet is said to have had 170 barrels on board, and one of the barges,

it is now asserted, was loading while the other was being unladen.

A public meeting was held on Monday evening at the "Pier Hotel," Erith,

for the purpose of taking into consideration the serious amount of

damage done to the property in the district, and to adopt such

resolutions as might be considered necessary with reference thereto. The

Rev. Archdeacon Smith, vicar of the parish, was called to the chair, and

was supported by the Rev. J. G. Wood, M.A.; Captain M'Killop, R.N.;

Captain Morell, R.N.; Dr. Hatton, and the churchwardens. A resolution

was put and carried, to the effect "That the disaster which has recently

occurred in the neighbourhood proves clearly the impropriety of large

quantities of gun powder and explosive matter being allowed to be

manufactured or stored in the vicinity of populous places, and that

communications be made to the Home Office and to the local magistrates,

pointing out the danger attending the establishment of gunpowder

magazines and warehouses in such places, and urging the discontinuation

of existing licenses, and the refusal to grant new licences for the came

purpose in future.”

A committee was formed with instructions to consider the mode of

carrying powder in barges, and proper representations would be made to

government on the subject. It was next decided to adjourn the meeting

until after the inquest, in order to obtain some idea of the amount of

claims for compensation. Votes of thanks were unanimously accorded to

the military and the medical gentlemen who so promptly attended the

sufferers. A vote of thanks to the rev. chairman concluded the

proceedings.

The Inquest.

The inquest was opened on Tuesday morning, at the "Belvedere Hotel,"

about a mile and a half from the scene of the disaster, by Mr. Carttar,

coroner for West Kent, and a jury of 17 of the most influential

inhabitants of the district. The room in which the inquiry was held had

almost every window smashed, and the weather being excessively stormy,

the task of conducting the inquiry was by no means a pleasant one. The

inquest was held upon the dead bodies of three persons which lay

comparatively entire on the ground in the coach-house in the hotel yard.

The remains of Mr. George Rayner, aged 40 years, the foreman to Messrs,

Hall, lay on a mattress, covered up with his own coat. Next him lay

those of Thomas Hubbard, aged 52, and John Yorke, a boy of only 13.

Numbers of ghastly parcels were deposited on the floor of the outhouse,

and their blood-stained appearance gave a sickening indication of there

contents. In them were collected different portions of human bodies,

supposed to be the sole remains of the men Wright and Yorke, who were

known to have been at work in the magazine at the time of the explosion.

In addition to the men whose lives are thus known to be lost, we may

state that, on board the barge Harriott, belonging to Messrs. Monk and

Co., were known to have been John Dadson, captain, Daniel Wise, mate,

and William Dadson, son of the captain. On board the barge Good Design,

belonging to Messrs. Hall, were William Jemmett, captain, and Lake

Barber, mate. All these human beings completely disappeared along with

the barges, and not a trace of them has as yet been found. The scene of

the explosion can be viewed from the "Belvedere." 300 marines are

still

actively at work strengthening the temporary embankment, for the wind

from the north-east was high, and threatening. All apprehension of the

giving way of the barrier is now, however, laid, and the measures still

in progress are designed to render assurance doubly sure.

The jury having been sworn, the Coroner opened the proceedings with a

short address. He said that the jury would find their duty an anxious

and onerous one, but he was sure that so respectable a body of jurymen

could not fail to give satisfaction to all parties interested in the

proceedings and to the world at large. There was no tribunal so well

qualified as the coroner’s court to investigate, not only the fact of

the deaths of persona killed by great calamities, but; for the inquiry

into the circumstances attending the occurrence. It was not necessary

for a person to be charged at the bar as in other courts, and they were

not therefore restrained from going into evidence that did not strictly

bear upon the one point of the guilt or innocence of that parson. His

own knowledge of such calamities was, he was sorry to say, not limited.

He had too frequently been called upon to inquire into the causes which

resulted in fatal explosions, but this was the first instance in which

he was concerned in the case of an explosion of a powder magazine or

store-house. He would not prejudge the present case by a word. He knew

nothing of it but by the general reports which was known to all. But he

was confident that from Messrs. Hall and the other proprietors the court

would obtain every facility for arriving at a satisfactory conclusion,

and it was for the jury to see what recommendations they might deem it

useful to submit to the consideration of Government for the regulation

of such establishments. It was deemed necessary to prohibit the storage

of more than a certain quantity of petroleum and fireworks, and it was

hard to say why no limit should be placed upon the amount of gunpowder,

which was the most dangerous compound of all. That was, however, merely

his own suggestion. Without doubt it was true that even the explosion of

a very small quantity of powder would as effectually destroy the lives

of all on the spot as would the explosion of an enormous quantity. But

there could be no comparison of the results in respect to the

destruction to property and life and limb in the surrounding districts.

In all the districts bordering upon the metropolis houses were springing

up, and the population was becoming denser year by year, end therefore

the question of the storage of highly dangerous compounds was of the

utmost importance and whatever time the court might bestow upon the

matter would not be thrown away. He proposed, in the first instances to

take evidence as to the identification of the deceased persons as far as

it could now be obtained. He would then take the evidence of two or

three witnesses: but (said the learned gentlemen, referring to the

fearful state of the room in which the jury were assembled, and through

the apertures of which the wind roared and bawled) I do not wish after

the loss of life that has already taken place, to jeopardise your lives

or your heath by going on with the proceedings here. If you think it

requisite, we can walk to the site of the powder magazines, and inspect

the place, but I believe not much information is to be gained by doing

so.

Several of the jurors stated that they had nearly all visited the scene

of the explosion, and it would only be a waste of time to proceed there

now.

Mr. Poland then rose, and addressing the court said that he appeared on

behalf of Messrs, Hall and Son, the proprietors of one of the powder

stores, and he wished to state that it was the desire of those gentlemen

to give every facility and requisite information to the court. If the

result of the inquiry should show to them any improved method of

conducting their business, so as to conduce to the safety of all

concerned, they should feel deeply thankful.

The jury having viewed the bodies and returned to the inquest room,

Walter Silver, who appeared at the table with his head bound, having

been injured by the explosion, was called to identify the bodies. He

stated that he formerly resided close to the magazine but his

dwelling-house had been razed to the ground by the explosion. He was a

storekeeper in the employ of the Low-wood, Liverpool, Gunpowder Mill

Company, Limited. The establishment was formerly known as Day, Barker,

and Co., and their offices were 63, Fenchurch street. He then identified

the bodies lying in the neighbourhood of the inquest-room as those of

George Hubbard, a labourer engaged in buildings erected near the

magazines, and as one not at all conversant with the works. He also

identified the body of G. Rayner, who was the foreman of the magazine

and that of John Yorke as the son of William Yorke, under storekeeper,

who is missing.

Mr. Sydney Turner, house-surgeon of Guy's Hospital, was next sworn and

said:- I have under my care some of the persons injured by the

explosion. With the exception of Eliza Osborne, who is in a dangerous

state, all the rest are doing well. The youngest is six and the next is

a girl of nine years of who is sufficiently well to be examined, and

indeed could be examined today. Edward Singleton has a fractured

humorous, and cannot be examined for a month, Emma Wright a woman of

forty, has a fractured collar-bone, and will not he able to be examine

for three weeks. Mary Yorke, who has a fractured thigh, is not likely to

be able to be examined for six or seven weeks. Another under my charge

is Harriet Rayner, the widow of the man who was killed, and she is

suffering from a severely contused shoulder, and cannot be examined for

a week or two.

Thomas Churton, of Erith, sworn, stated that he was a surgeon, and

described the condition of some of the mutilated portions of bodes, part

of which, he believed, belonged to one of the unfortunate man named

Wright. He also described the condition of two children, one six years

of age named Sims, and another named Yorke, twelve years of age, very

seriously injured.

The Coroner then stated that his object in taking this evidence was to

ascertain when it would be possible to proceed with the inquiry, and

obtain a narrative of the occurrence from the mouths of those who

actually experienced its effect.

Police-sergeant 15 R stated that seven persons were yet missing, of whom

no tidings could be obtained, five of them being from the barge, but,

subsequently, one of the legal gentlemen present in the room said that

one of the missing parties had since turned up and was safe at home.

This being all the progress that could be at present made, the inquiry

was adjourned till next Tuesday, at the Avenue School-room, Erith.

|

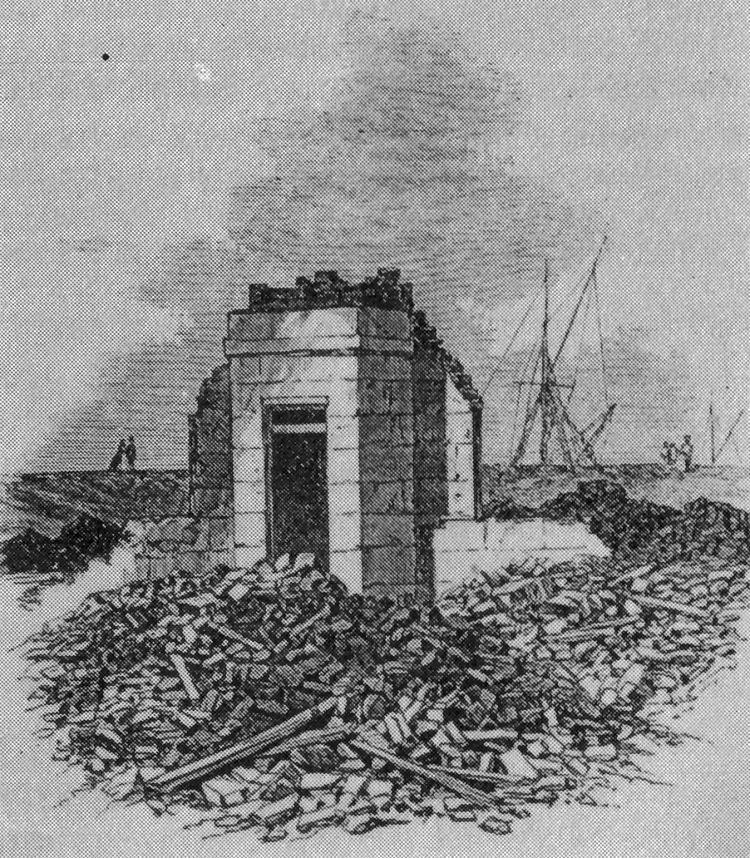

Above engraving showing remains of George Rayner's House. |

|

Maidstone Telegraph, Saturday 8 October 1864.

THE EXPLOSION AT ERITH. LATER PARTICULARS.

Another death, indirectly attributable to the catastrophe, occurred on

Sunday night at the Erith station of the North Kent Railway. A

young Italian, named Luigi Lorandi, or Marandi, in attempting to enter a

carnage in a general rush which was made for places on

the arrival of an up train, was dragged among the wheels, and sustained

mortal injuries. He was brought by the same train to

London, and taken to Guy's Hospital, arriving there at half-past twelve

o'clock. He had received a compound fracture of the right

thigh just above the knee joint, and the whole of the leg below was much

lacerated and contused, he was in a state of collapse and

almset pulseless. Mr. Sidney Turner, the house surgeon, decided that

amputation was necessary to afford even a chance of

recovery, small though it would have been; but the unfortunate man could

not be prevailed upon to submit to the operation. He

died three-quarters of an hour after his admission to the hospital. His

own account was that he was pushed under a carriage while

the train was starting, and that the wheels went over his leg. He was a

young man of gentlemanly appearance and gave an address

at 54, Goswell road.

For hours on Sunday night fearful scenes of tumult and violence occurred

at the Erith and Belvedere stations on the North Kent

Railway. Throughout the whole day thousands of people went by the line

from London and the intermediate stations to the scene of

the catastrophe, and a great number of them lingered there until dark.

The result was that until far towards midnight they

congregated in dense masses on the station platforms at Erith and

Belvedere, and besieged every train that stopped to take up

passengers on the up journey. The railway authorities at the London

bridge station dispatched extra trains one after another, as fast

as they couid do so with safety, to bring up the people, but in spite of

that there was great delay, and the last up train did not leave

the Belvedere station until 3 o'clock yesterday morning. At intervals

during the whole evening whenever a train stopped, either there

or at Erith, a frightful rush was made at it, and the people crowded the

carriages almost to suffocation, in spite of the efforts of the

police and the railway company's servants to restrain them. Many

clambered upon the tops of the carriages, others took possession

of the engine tender, and some even bestrode the buffers until they were

pulled off by main force by the police. At Woolwich

Arsenal station several of the trains were stopped, and people who were

suffering from the overcrowding taken out of them.

On Sunday and Monday pieces of the mangled and mutilated remains of

persons who perished in the explosion were found here and there in the

neighbourhood and taken to a shed at the back of the "Belvedere Hotel," where the bodies of Rayner, the

storekeeper, a man named Hubbard, and a boy (at first supposed, but

erroneously, to have been the son of Rayner) awaited an

inquest. Among these ghastly relies are a right and a left foot,

portions of a skull, and part of a jaw with a whisker, all apparently

beyond identity.

From the accounts rendered by the proprietors of the magazines, who are

best able to speak upon the subject, it appears that the

whole quantity of gunpowder which was exploded amounted to about 1,040

barrels, or 104,000lb., there being 100lb. to a barrel. Of this, 75,000lb. were stored in the magazine of Messrs. Hall, 20,000lb.

in their barges which were being unloaded at the time of the

explosion, and 9,000lb. in the depot of the Lowood Gunpowder Company, or

which is commonly known as that of Messrs. Daye-Barker and Co., the previous owners. The Lowood Company were expecting a

large supply of powder from their mills at Newton-in-Cartmel, Lancashire, which had been delayed through export and other

orders deliverable at their other depots. Their magazine at

Belvedere was about 40ft long by 30ft. in width, and consisted of two

floors. It was erected about four years ago, and stood at a

distance of 60 or 70 yards from that of Messrs. Hall. Like that, too, it

had a wooden jetty projecting into the river for the loading and

unloading of gunpowder. No one had entered it on the morning of the

explosion.

On Tuesday the number of persons killed and wounded by the explosion had

been ascertained with tolerable accuracy. Fire had

died, and there were five more missing—namely, a man named Wright, who

was employed as under-storekeeper at the magazine of Messrs. Hall, and four men who navigated the two barges that blew up.

The names of the latter are William Jemmett, master, and

Luke Barker, mate, of the barge Good Design; and John Dodson, captain,

and Daniel Wise, mate, of the barge Harriet. The dead

are George Raynor, storekeeper at the magazine of Messrs. Hall; John

Yorke, a boy of 13, employed there; Elizabeth Wright, about

the same age, daughter of the missing under-storekeeper; and John

Hubbard and James Eaves. The two last named were labouring

men unconnected with the magazines, but who were engaged in constructing

a river wall in their immediate vicinity. At the time of

the explosion they were collecting their tools in an outhouse attached

to the cottage of Walter Silver, the storekeeper at the Lowood

magazine, preparatory to beginning work for the day. Seven of the

sufferers were at Guy’s Hospital, and all doing well, with one

exception. There are also a few others in and about Erith, who are more

or less injured. One of these John Simms, a boy of 11, was

gathering mushrooms, with an elder brother, at the time of the explosion

about 100 yards from the principal magazine. He sustained

serious injuries, but his brother escaped unhurt. He was struck on the

head with what he thought was a brick, and which tore off

the scalp at the back and depressed a portion of the skull partly upon

the brain. He was under treatment by Dr. Tipple, of Erith, and

hopes were entertained that he may recover. William Yorke, aged six

years, a younger brother of the boy John Tarke, who was

killed, was picked up among the ruins just after the explosion, badly

injured. Two pieces of wood about two inches and a half long,

and one a quarter and the other half an inch thick, have since been

extracted from his head, where they were completely buried,

and one of which pressed upon the brain. Captain M'Killop kindly took

the poor little sufferer into his house, where he remained in a

somewhat precarious state. Three children, between eight and eleven

years of sge, were staying with Walter Silver at the time of the

explosion. One of the three, Samuel Fletcher, his nephew, he had sent to

post a letter. The boy had just left the cottage when the

explosion was heard, and he was thrown down and had two of his ribs

broken. He was at the moment passing the man Hubbard,

who was killed on the spot. Another of the children escaped with a few

scratches, while a third, Elizabeth Osborn, with whom it was

playing, received injuries from which she is not expected to recover.

The escape of Silver himself was little less than miraculous. He

wase straining milk through a sieve just within the back door of his

cottage when he was startled and thrown down by the first

explosion in the barge, while the second and still more appalling one in

the magazine shattered the house about his ears. He was

afterwards dug out of the ruins with a few bruises about the head and

body, and has since been going about.

A public meeting has been held in Erith with the view to obtain

compensation for the serious damage occasioned to property in the

town and neighbourhood by the explosion, or, at all events, protection

from any similar catastrophe in future. It was attended by the

principal inhabitants of the place, and also of Belvedere. Archdeacon

Smith, the vicar, who acted as chairman, commented upon the

vast and almost overwhelming calamity which had suddenly befallen that

district. There were, he said, some points connected with

the catastrophe which were not unworthy of remark. Among these were the

seal and alacrity displayed by the entire population to

render every aid under the direful circumstances, and the singular

sobriety and praiseworthy demeanour manifested by the

thousands of persons, from remote places, whose curiosity led them to

visit the spot. They had indeed, reason to be thankful for that

ready aid, which doubtless prevented a mighty river from asserting its

dominion, and again flowing over the broad acres where it no

doubt at one time found its original bed. The great sacrifice of

property was, after all, as nothing when compared to the sacrifice of

human life; and he hoped it would go forth to the world that the

sympathy of that meeting with their fallen brethren was

paramount. He conceived that the meeting had assembled for two objects.

First, it desired to make a well-considered and temperate

expression of regret, or he might indeed say remonstrance, against the

re-erection of powder factories so near populous localities;

and they wished also to consider the question of loss and compensation,

and to come to some decision as to who was responsible.

Resolutions were afterwards passed to the effect that the disaster

clearly proved the impropriety of large quantities of gunpowder

and other explosive materials being allowed to be manufactured or stored

in the vicinity of populous places, and that

communications be made to the Home-office and to the licensing

magistrates pointing out the dangers attending the establishment

of gunpowder manufactories and warehouses in such places, and urging the

discontinuance of existing licences and the refusal to

grant new ones for such places in future. A committee composed of 17 of

the chief inhabitants, with the Archdeacon at their head,

was appointed to carry out the objects of the meeting. The committee was

also instructed to consider the mode of carrying

gunpowder in barges and the dangers attending it, as pointed out by

Capt. M'Killop, with a view to make a proper representation to

the Government on the subject. before separating the meeting passed a

unanimous resolution marking their high sense of the

services rendered by Mr. Moore, civil engineer, Mr. Webster, the

contractor at Crossness Point, and his men, and of the military

authorities at Woolwich, on the sad occasion,—services which, by the

speedy restoration of the embankment of the river, tended to

preserve a large district of country from inundation. It was stated that

Messrs. Hall had undertaken to provide for the widows and

orphans of the man who perished by the catastrophe.

On Tuesday Mr. C. J. Carttar, one of the coroners for the county of

Kent, opened an inquest at the "Belvedere Hotel," Belvedere, on

three of the bodies which lie there. The jury was composed of about 17

of the principal inhabitants of the neighbourhood, and

Captain M’Killop, of Erith, was chosen foreman.

The Coroner, addressing the jury, said their duty would be a very

anxious one, and one which he was sure, from the respectability

of the gentlemen composing the jury, would be conducted in a way to

afford satisfaction to every one concerned in the inquiry and

to the world at large. The Coroner's Court was so well constituted, and

so peculiarly adapted for inquiries into life and death and into

the surrounding circumstances, that no better tribunal could in the

first instance be reported to for the investigation of any

deplorable calamity. It was not necessary in that, as it was in a

criminal court, that persons should stand at the bar for an offence.

On the contrary, that was a court purely for inquiry, in which none

could be charged with a criminal offence, unless, indeed, evidence came out tending to implicate them. They would, therefore, be

enabled to hear a vast deal of evidence which in other

courts would not be considered legally admissible, and thereby to arrive

at some conclusion which would duly account for the death

of the poor unfortunate men in question, and be the means, he should

hope, of averting in future so sad and deplorable a

catastrophe as that which had occurred on this occasion. He would not

anticipate the evidence that might be adduced before them.

His own experience had unfortunately much too often led him to

investigate calamities of this description. He had had to inquire, as

coroner over a jurisdiction including a great arsenal, into the deaths

of many persons by the explosion of gunpowder, but in those

cases he and the jury assisting him had never been able to get at the

cause, and for this reason—that all those immediately

surrounding the spot at the time of the occurrence were killed

instantaneously. He had not before had to inquire into the explosion

of a magazine for the storage of gunpowder. His experience had reference

to explosions of factories where gunpowder was in

course of fabrication, but not in a state of completion, and in all

those cases they had never got at the cause of the explosion. In this

case they must do all in their power to hear everything and everybody in

reference to the matter, and if they could not discover the

exact cause of the catastrophe they might still know with what

precautions to surround the manufacture and storage of gunpowder,

its loading and unloading, and its transit, and consider whether there

ought not to be some limit to the quantity stored in one place

and to the distance of a magazine from human habitations. He should

express no opinion on the subject of quantity at present, but

after they had performed their duty of attempting to inquire into the

first cause of the explosion they might then see whether there

were any and what additional precautions that might be adopted in the

care and management of powder magazines, and which it

might be desirable for the government of the country to enforce. It was

quite manifest, whether the quantity of powder stored in a

particular place was moderate in proportion or enormously large, that

death would occur in either case from an explosion; but if the

quantity was moderately small there would probably be fewer persons

living about the magazine than otherwise, and, on the other

hand, the result of the explosion of a magazine enormously filled with

gunpowder was that it effected the surrounding locality for

eight or ten miles round. If therefore, for that purpose only, some

check or limit were placed to the quantity stored in one spot, the

consequence of explosion might be lessened in the immediate

neighbourhood, and a vast protection be secured to populations in

the vicinity of London, which was being extended in every direction. A

limit was placed on the quantity of petroleum and of fireworks

deposited in one place, and he thought, seeing that the most dangerous

of all was gunpowder, there ought to be some limit in

regard to the quantity stored in a given spot.

The jury, accompanied by the Coroner, then proceeded to view the bodies,

which lay in a shed at the back of the hotel. The bodies

were those of two men and a boy. They all appeared to have died from the

injuries in the head principally. The face of the poor boy

was much swollen and blackened, and the skull of one of the men was

severely fractured. The countenance in each case was placid,

notwithstanding, and the probability is that the unfortunate creatures

were killed instantaneously. There were also in the same shed

detached portions of the mangled and mutilated remains of persons who

had perished in the catastrophe.

On the return of the jury the first witness called was Walter Silver, an

elderly man, whose head was in bandages. He said:- I resided

near the magazines, in a cottage which is now annihilated. I was

storekeeper at the magazine adjoining that of Messrs. Hall, and

belonging to the Lowood Gunpowder Company, who have an office at 63,

Fenchurch street. The magazine formerly belonged to

Bay-Barker and Co. I have just seen the bodies, in the presence of the

jury. The first is that of George Rayner. He was about 39

years of age, and was storekeeper to Messrs. Hall. I last saw him alive

on Friday evening, between six and seven. The second is the

body of Thomas Hubbard. He was about 50 years of age, and a labourer, in

the service of Mr. Cavey, a contractor. The deceased,

with others, had been engaged in making a river wall near the magazines,

and was not connected with the magazines. I saw him

last alive on Saturday morning in a shed in which they kept their tools,

close to my house. The third body is that of John Yorke. He

was about 13 years of age, and the son of a man now missing, and who was

under storekeeper to Messrs. Hall. I last saw the boy

and his father on Friday evening.

Mr. Sidney Turner, house-surgeon at Guy's Hospital, said he had now

under his care there seven persons who had been injured by

the explosion, all of whom were doing well, except a little girl named

Osborn. Nine were at first received into the hospital, but two

had since died.

Mr. Thomas Churton, a surgeon at Erith, said he had seen the human

remains which had been found. Among them were three feet,

two of which appeared to be a pair, and some whisker, which he thought

he recognized as that of the misting man Wright, whom

he knew. He had now two children under his care at Erith, one six years

of age, and the other 12 or 13. They were suffering from

fractured skulls.

This being all the progress that could be at present made, the inquiry

was adjourned till October 11 in order that in the meantime

the evidence might be procured and marshalled.

|

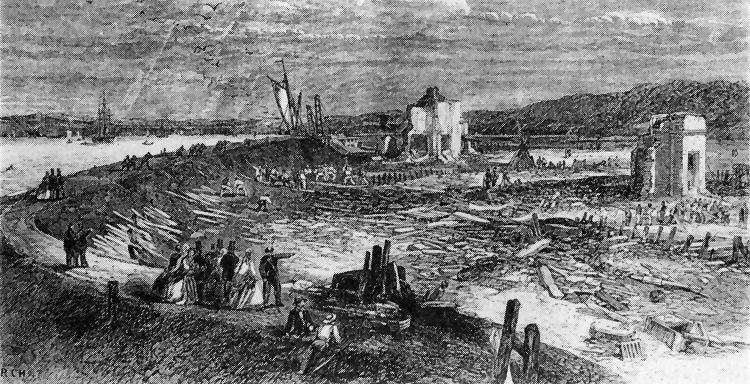

Above engraving showing aftermath of explosion 1864. |

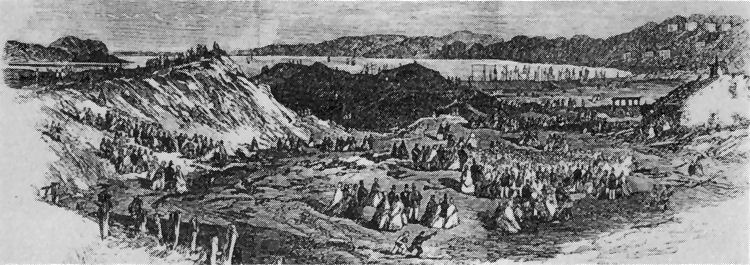

Above engraving showing the sightseers viewing the explosion. |

Above engraving showing the remains of Walter Silver's house. |

|

Kentish Chronicle, Saturday 15 October 1864.

Gravesend Reporter, North Kent and South Essex Advertiser, Saturday 15

October 1864.

THE EXPLOSION AT ERITH.

We regret to state that another death has resulted from the recent

explosion at Belvedere. On Monday, the girl Elizabeth Osborn

expired at Guy’s Hospital, from serious wounds on the head and arms

which she received from the falling debris after the explosion.

Her case was almost hopeless from the first. The death of this sufferer

makes the total number of lives lost by the late calamity

amount to twelve. The rest of the wounded in Guy's Hospital are reported

to be in a fair way towards ultimate recovery.

The adjourned inquiry at Erith was resumed on Tuesday, before the

Coroner for West Kent, Mr. C. J. Carttar. The inquiry took place

in the Avenue-hall, Erith, which had been fitted up for the occasion,

and placed at the disposal of the coroner and jury.

The first witness called was Mr. F. A. Tipple, of Erith, surgeon, who

said:- The first body that I saw was Rayner, who was dead, the

second was that of Hubbard, who was lying upon his back away from the

ruins of Silver's house, quite insensible. There was a

severe fracture on the back part of his skull, and the brain was

protruding. He lived about two hours from the time of the accident. I

also attended, with Mr. Chappel, upon all the other injured people.

By the jury:- Rayner was nearer Silver’s house than his own. He was, in

fact, about midway between the two.

By Mr. Perrin:- The boy Lewis is suffering under fracture of the skull,

besides other injuries, and his case is a bad one.

John Silver recalled:- At the time of the explosion I was in the

washhouse, pouring out milk. I had been out that morning, but not

to the magazine. I belong to the Liverpool company. There was no barge

loading or unloading at our magazine that day, but there

were two barges at the Messrs. Hall's magazine, but whether they were

loading or unloading I cannot say. When the explosion took

place I was standing at the washhouse door. I could not say from whence

the explosion came, because it was all dark in a moment,

and I felt the bricks tumbling on me. I had half a pound of gunpowder in

the next room, and my first thought was that that had

exploded; but before I had time to think I heard a second explosion, and

I felt more bricks tumbling upon me, but whether I was

knocked down or not I do not know. When I came to myself I found that I

was lying on the ground among the ruins. Our magazine

had not been open at all that day. We generally open it every day to

give the place an airing. Our windows are lattice

windows, and I generally open them a little way, and put a piece of wood

in to keep them open. No one is allowed in the magazine

when three is no business going on. I know Messrs. Hall’s magazine. It

is constructed like ours.

By the Jury: Our magazine was about twenty yards from the wall of the

Thames, and that of Messrs. Hall was about the same

distance. The distance between the two magazines was about seventy

yards.

The Coroner stated that, as far as distance was concerned, it would be

all important to have the moat accurate information, which

would be forthcoming. At present he proposed to ascertain, if possible,

the exact spot where the explosion took place. This witness

would be recalled.

Samuel William Fletcher, a boy thirteen years of age, was next called,

and said:- I got up about halfpast five o’clock on the morning

of the explosion, and had been at the back of the house milking the cow.

I was standing at the door, and heard some one say "Oh,"

and I saw a flash come from the barge towards the magazine. I could not

see the barge, but I saw the sails, and saw the flash

distinctly. I then felt a blow, and I heard and saw nothing more till I

came to myself, when the first words I heard was about

somebody (Singleton) breaking his arm. I then noticed Rayner’s magazine

flaring. I believe it was the magazine, and not the house.

It was towards Rayner's magazine that I saw the flash go from the barge.

By Mr. Perrin:- I had seen the barges the evening before. They were on

the lower or Erith side, one of them being alongside the

jetty.

By the Jury:- Mr. Hubbord was near me when the explosion tool place, and

it was him who cried "Oh!" to me. He was in the shed. I

did not see him come from the spot; he was lying on the ground looking

like dead. I saw him before the explosion, but did not

notice that he had any pipe. Both the barges had sails. We once boiled

the kettle for the bargemen in Silver’s house. I have seen

barges there before, but have never seen fire on board, or smoke coming

from them. I have never seen any of the bargemen

smoking.

Thomas Richardson, the older, examined:- I live at 9, Queen-street,

Greenwich. I am a fisherman. On the morning of the explosion I

was sailing and rowing down tho river in a fishing boat. I was about 150

yards from the shore of the river, and nearly abreast of the

upper jetty. There was very little wind. I don’t know whether I saw one

or two boats lying at the jetty. My little boy said to me,

"Father, there are some men at work, I think it must be getting late." I

looked towards the barge and saw men at work. The next

instant, quicker than I can talk, I saw a dense cloud of smoke which

arose in the direction of the barge. I immediately pushed the

boy under the deck, and then I heard another most dreadful explosion,

and a large stone passed just over where the boy had been

sitting, and another struck me on the side of the head and stunned me

for a minute or two. When I came to myself the smoke had

cleared away, and I heard cries as of injured and drowning men, and I

helped to rescue one. The second shock was the most

dreadful, and quite lifted the boat out of the water.

Thomas Matthew Richardson:- I am the son of the last witness, and was

with him in the boat on the morning of the explosion. I was

looking in the direction of the barge by the powder magazine, and saw

men wheeling. I told my father that men were at work, and

directly after that I saw a great black smoke and heard a noise. The

smoke was from the stern of the barge. I was pushed down into

the cabin, and then I heard another shock, and my father and I fell down

together. I saw a screw-steamer on the north-side of the

river a moment or two after I saw the smoke.

By Mr. Poland:- I saw the smoke before I heard the noise. There there

two barges at the jetty, one lying alongside the barge, and

the other alongside. I saw the smoke come from the stern of the barge

that was lying across the head of the jetty. The noise of the

explosion was immediately after I saw the smoke, and the whole thing

blew up. I saw the steamer coming down with the tide.

Robert Bruce, a ballast man on board the ballast lighter No, 32, said:-

On the morning of the explosion I was on the barge and well

over to the south side of the river, that being the set of the tide. The

wind was blowing east. Clarke and Grimes were on board with

me. What first drew my attention was a great flash of light all round

me, and a shower of bricks, and we were all knocked down. I

had seen the barges before and noticed that there was a boy on board the

barge lying across the jetty, the head lying up the river.

It was abreast the jetty at the time of the explosion. I heard the

second explosion, which was worse than the first. There was a

terrible lot of smoke. Grimes was knocked over the boat, and I caught

hold of him by the hair of the head. He was dreadfully

injured. We went into Erith to get assistance. I noticed a steamer after

the explosion. She was steaming down the river in Harbour-reach, the wind being dead against her, so that any sparks that came

from her must have blown away from and not towards the

magazine. I expected they would lower a boat down and send assistance,

but they did nothing of the sort, but simply passed on.

A number of witnesses deposed to witnessing the explosion, but giving no

information as to its cause.

Robert Gray, of Randall-street, Erith, deposed that he was on Erith pier

head when the explosion took place. He was striking a light

for his pipe when he heard a violent noise, then saw a flame and a vast

mass of smoke. It formed itself into a beautiful column, and

then flame burst out. This took place before the second explosion, and

it was on the water side.

William Eldred, Plumstead, employed by Mr. Cavey in unloading barges at

the chalk wharf, deposed:- I arrived at the wharf about

twenty minutes or a quarter to seven, across the marshes. There were

seven of us in company, two of whom are dead and two

injured. Singleton and Eves came about a minute or two before the rest,

and unlocked the door. We had no pipes, not one of us

was smoking. I just went into the shed to get a drop of beer which was

in a bottle when the explosion took place. There were two

barges lying at the jetty, one at the side and one at the end. The first

explosion blew the roof off the shed, and the second, which

was the heaviest, knocked down all the bricks about us. I got up myself.

I never smoke; and, though I have known the men to

smoke when on their own wharf, I have never seen them smoke when at

Silver’s wharf, not even when putting away their tools.

By Mr. Poland:- I have never seen any fire on board any of the barges.

Rayner was a very careful man, and generally respected.

Samuel Johnson, another of the seven labourers at the chalk wharf, was

called, and confirmed the evidence of the previous witness.

John Smith, another labourer, was called, and declared in the most

positive manner that there were none of the men in the party

smoking that morning.

The other survivors of the party were then examined, and described the

accident, but their evidence was a mere repetition of that

already given. One of them (Norris) said that he was blown a distance of

thirty feet from the ground by the force of the explosion. None of the men could give the least idea of the precise spot at which

the first explosion occurred.

Mr. H. A. Howe examined:- I live at Messrs. Curtis and Harvey's

magazine, which is the next one up the river. I was in the magazine

at the time of the explosion. I heard nothing but a hissing noise and

things falling about, I stepped out to the door, and halfway

between one magazine and that of Messrs. Hall, I saw a screw steamer

lying almost on her side. At the same moment I saw a dense

white smoke at the jetty, and almost instantaneously the powder magazines

exploded. I had seen men working there a few minutes

before, wheeling trucks. I had seen Mr. Rayner a few minutes before the

explosion in his garden. In Rayner's absence it would be

the duty of Yorke to see to the men loading or unloading the barges.

Yorke is entirely missing. He described the windows of the

powder magazines and the fastenings, which he said were ordinary ones,

but outside the glass, and the windows had ordinary

weighted sashes.

By the Jury:- It sometimes happens that a cask leaks. The casks are

passed from hand to hand, and if a leaky one is discovered it is

sent back to the factory, and not put with the rest of the powder

barrels.

Mr. Perrin:- Is there not a path leading to your magazine, and have you

ever had occasion to find fault with persons coming along

that path smoking?

Witness: Yes, and shooting too.

You never heard of any persons coming up to the magazine, or very near

to it, smoking?

I should like to catch them at it. I never did.

By the Jury:- Did you ever know the men bring the powder on the deck

covered with tarpaulin?

Witness:- I have known them bring it out of the batches, and then cover

it over with tarpaulin on the deck.

Is it possible for an explosion to take place by dropping a cask?

I think not; it is very seldom that one is dropped.

How far was this steam vessel you speak of from the shore?

It was, perhaps, three fourths of the way from our magazine towards Mr.

Hill’s, but not near enough to it for any sparks to come

from her; the wind would not allow it.

Mr. Perrin:- What quantity of gunpowder do you store in your magazines

generally?

I cannot say; it depends on orders.

By the Coroner:- There might be occasionally from 800 to 900 barrels of

100lb. each. Sometimes the magazine would be three-quarters full.

By Mr. Poland:- Our licence under the Act of Parliament enables us to

store an unlimited quantity, and that licence is granted by the

magistrates in session. There is a caution board exhibited at the

magazine to this effect:—"Gunpowder magazine.—Caution.—All

persons trespassing on these premises, or loitering near them, or

smoking pipes, or firing firearms, or in any way endangering this

property, will be prosecuted."

By the Coroner:- Our works belong to Messrs. Curtis and Harvey, but the

barges belong to other persons. They are, however,

constructed exclusively for carrying gunpowder. I never allow a fire on

board, or smoking when the barge is at the wharf. I am not

aware that the regulation has ever been broken. It is only when the

barges are at the wharf that fire and smoking are objected to.

When the barge is out in the stream, and the hatches are battened down,

it is not objectod to, but it is a very different thing when

the barges are alongside the wharf, because then the hatches are open.

There is nearly always a current of air that takes the sparks

away from the barges when there is a fire on them.

After an adjournment of a few minutes, to enable the jury to obtain some

refreshment, the Coroner said that he had now gone

through all the evidence relating to the first of the two branches into

which the inquiry divided itself—namely, the ascertaining the

precise spot where the explosion first took place; and he now proposed

to enter into the second branch—namely, the mode adopted

of conveying and storing the powder, and the precautions adopted to

prevent accident in the loading and unloading of the barges.

A number of witnesses were accordingly examined on this subject; after

which the coroner said that it was impossible to finish the

inquiry that night, and as they had now sat over seven hours, he

proposed to adjourn.

After a short conversation as to the most convenient day, it was agreed

that the inquest should be further adjourned till that day

week, when the whole of the remaining witnesses would be in a condition

to be examined.

|

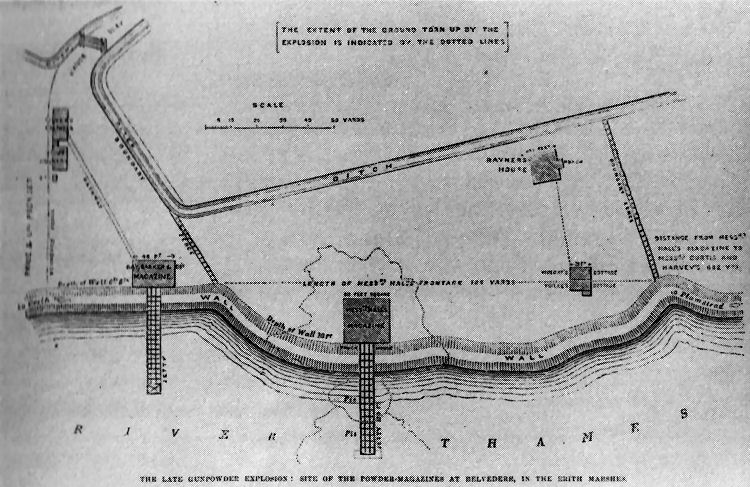

Above map 1864. |

|

Kentish Gazette, Tuesday 18 October 1864.

The Recent Explosion at Erith.

As might have been expected, the adjourned inquest held at Erith on the

persons killed in the late explosion has not bought to light any direct evidence on the definite cause of the catastrophe. We are

still left, as we probably always shall be, to form more or less

probable conjectures. Some eyewitnesses are able to tell us something of

what was going on up to within two minutes of the

explosion, but the fatal second in which it occurred has left none who

could tell tales. A boy in a fisherman's boat on the river saw

men on the jetty, who, as he thought, were wheeling little casks on a

truck. and the storekeeper at a powder magazine a quarter of

a mile off had seen a four-wheeled truck laden with powder go into the

magazine about two minutes before the explosion. There

can be no longer any doubt that the explosion first occurred in one of

the barges, and probably in the one which was being

unloaded. Two or three independent witnesses describe their having seen a

flash of light and smoke from one of the barges

immediately before the shock of the explosion reached them. There appear

also to have been four distinct explosions—first, of the

two barges, in rapid succession, and then of the two magazines. That is

about the extent of our information as to the circumstances

of the explosion, and such it is likely to remain.

But, whatever may be our ignorance of the actual cause of the

catastrophe, there is ample evidence to show not only that such a

catastrophe might easily have occurred, but that it is astonishing that

it never occurred before. The facts brought to light on

Tuesday, as to the dangers to which the barges and magazines are

exposed, are most startling and alarming. The admirable

precautions obscurely hinted in Messrs. Hall’s letter of Monday week,

and detailed to the satisfaction of the public on the inquest at

Guy’s Hospital, turn out to be mainly theoretical, and to be grossly

neglected in practice. To take first the case of the barges. It is

impossible to doubt, from the evidence on Tuesday, that the men do not

abstain from using a fire in the cabin when they have