|

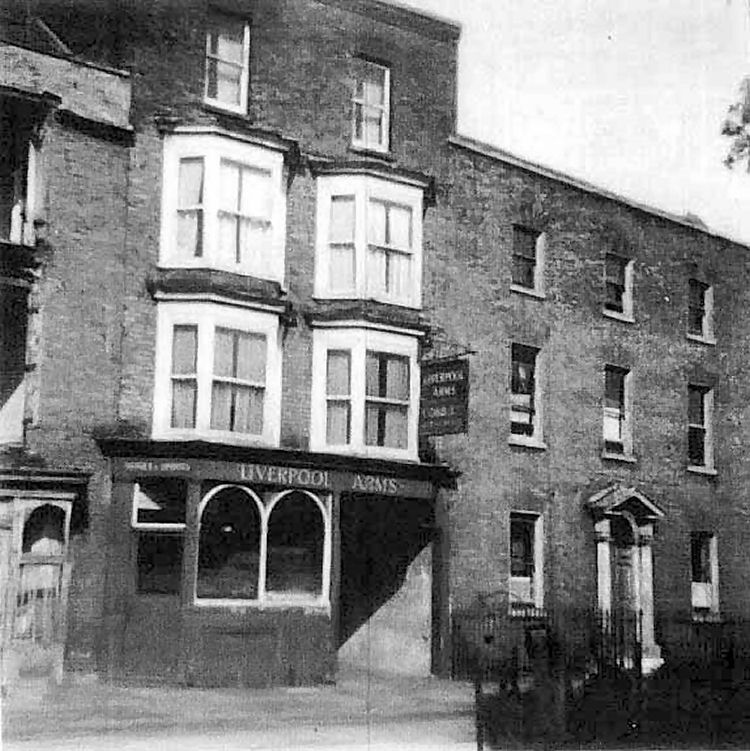

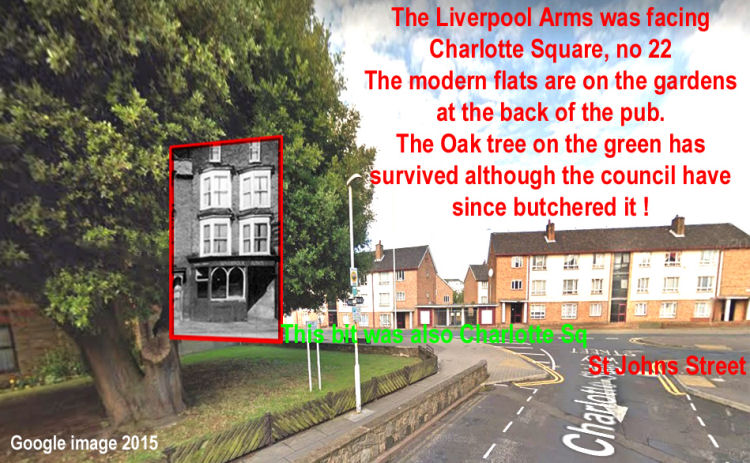

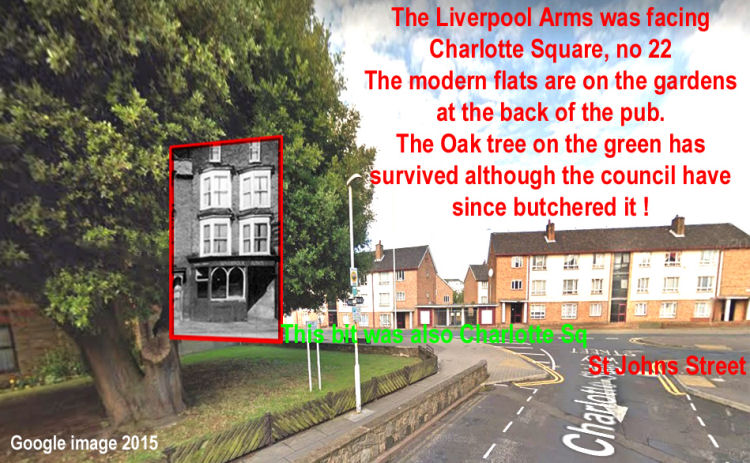

22 (19 in 1851 ) Charlotte Place ) Charlotte Place

Margate

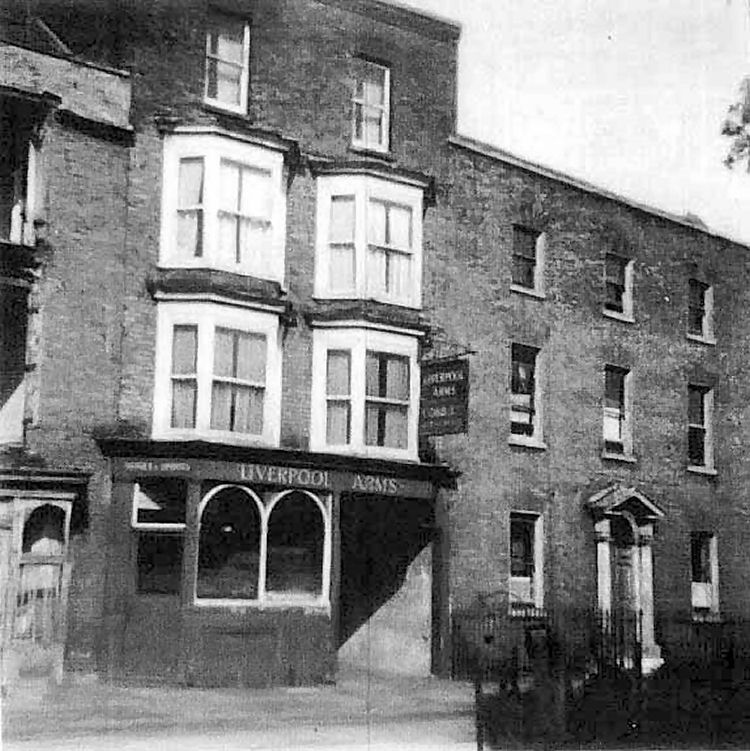

Above photo, date unknown. |

Above photo, date unknown. |

Above photo date unknown.

|

Above photo, showing a outing, date and people unknown. |

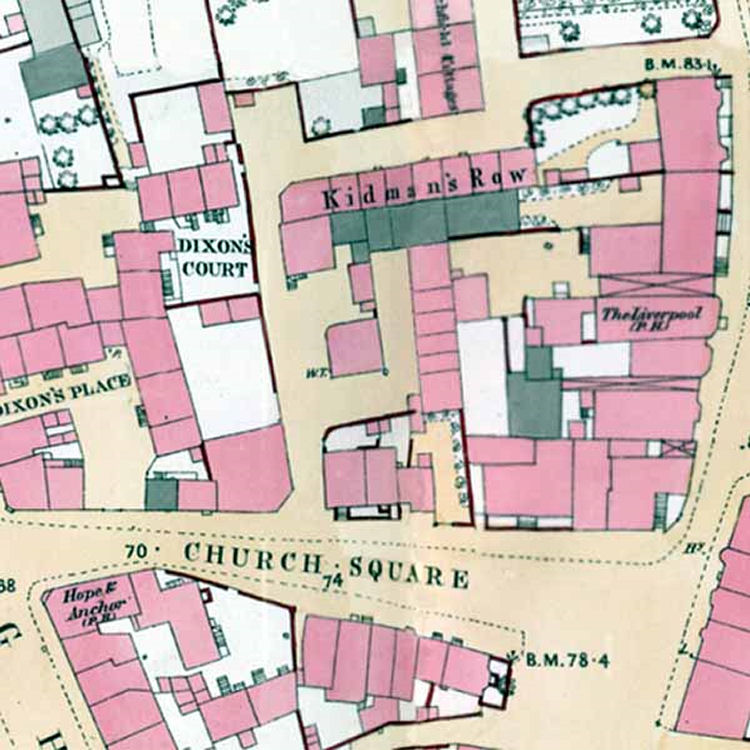

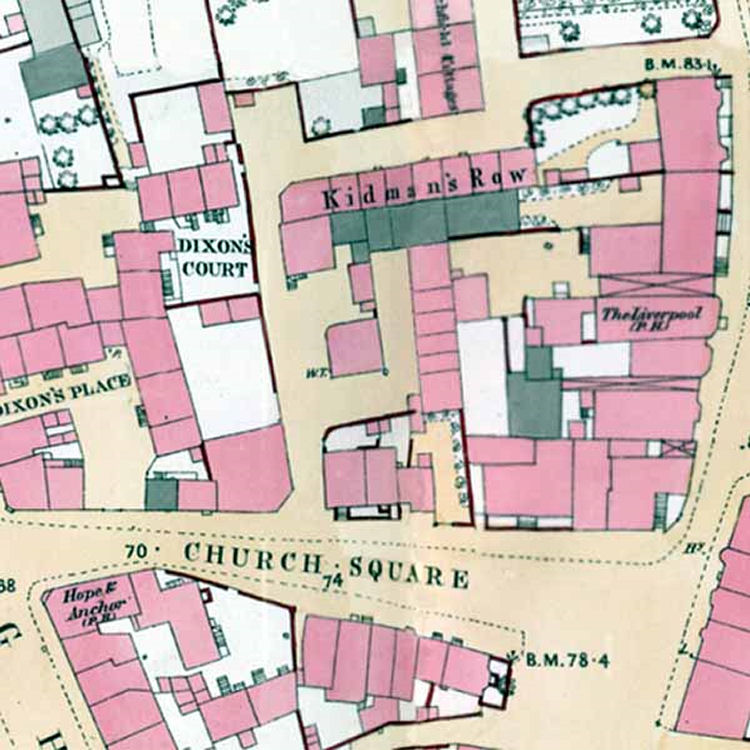

O S Map 1873. |

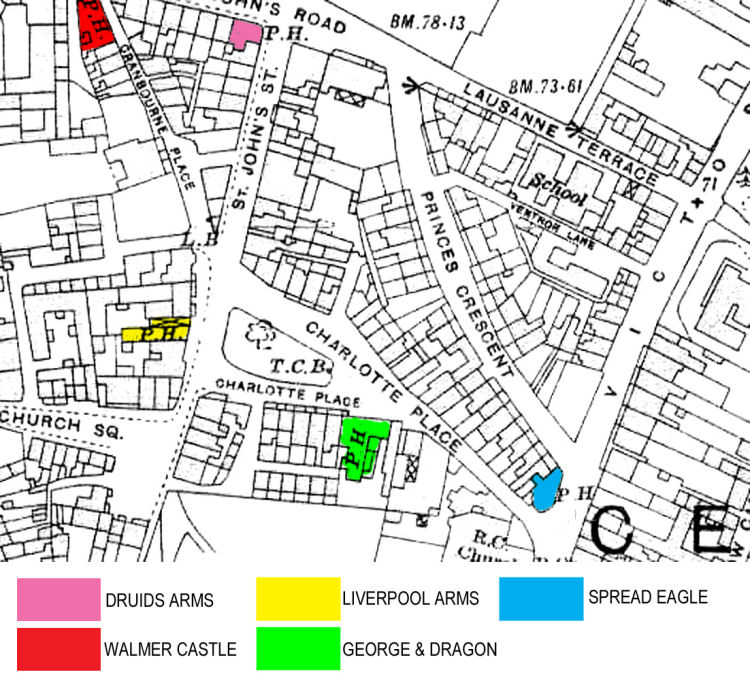

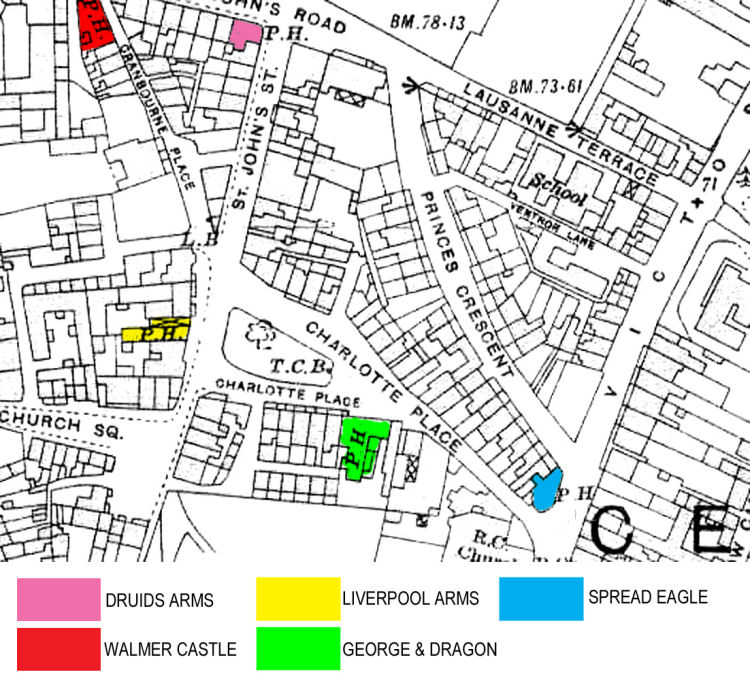

Above map 1948. |

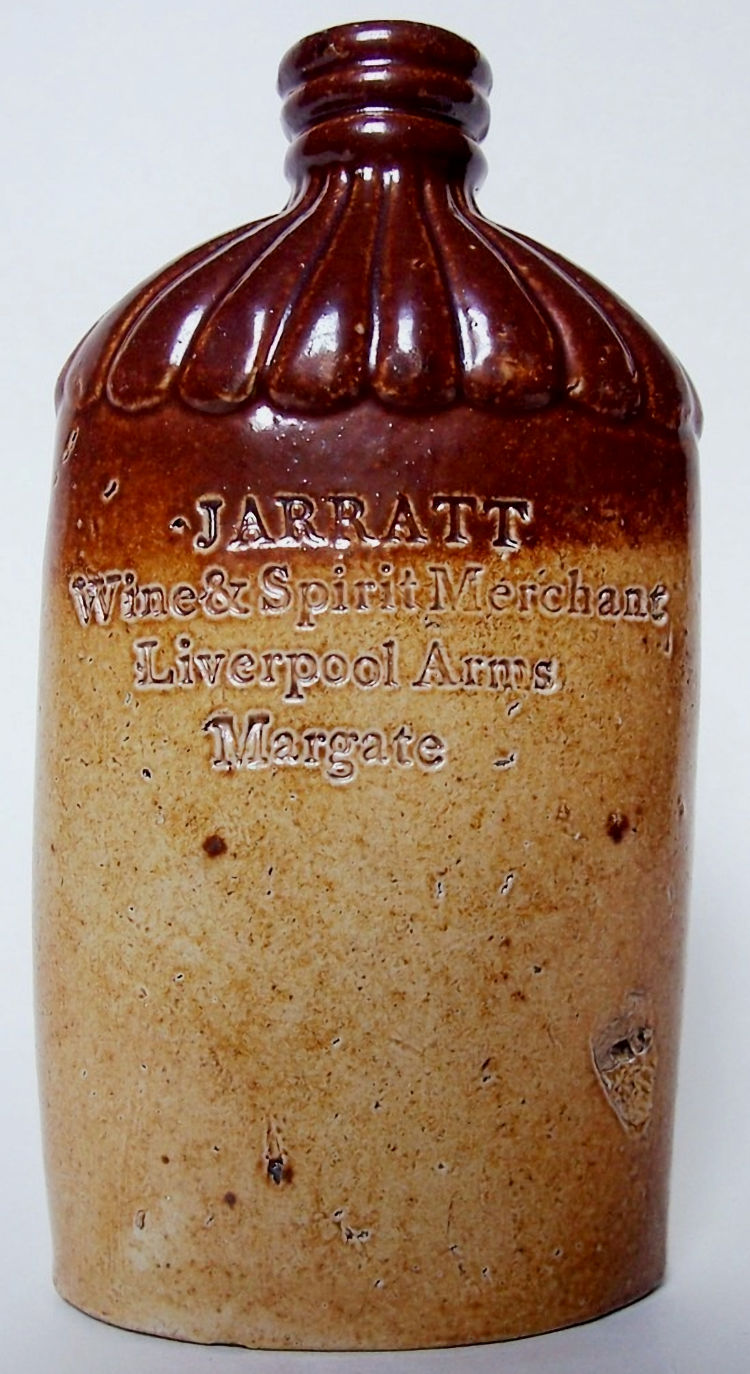

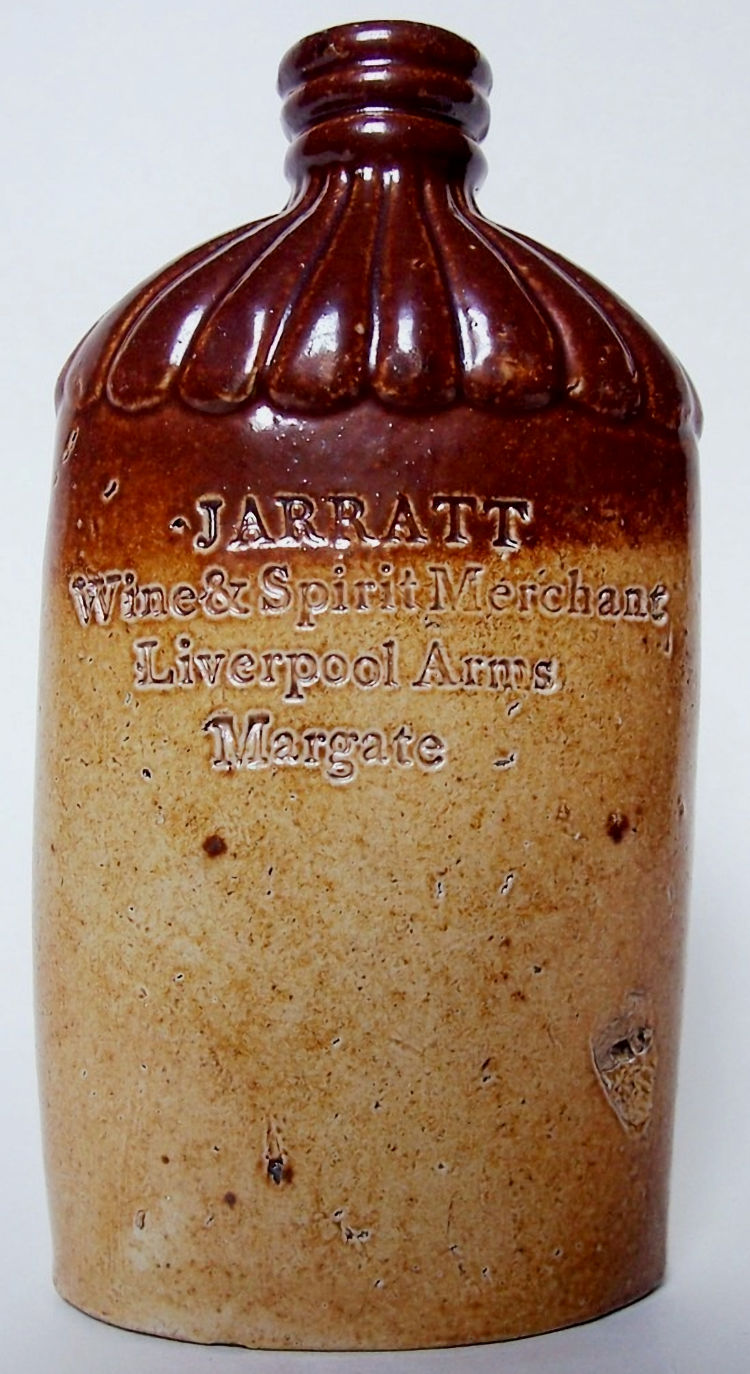

Above ceramic jar, circa 1845, kindly sent by Mary Ault, |

One time Cobbs tied house. Cobbs were founded in 1673, but Whitbread took

them over early 1968 and closed the brewery later that year.

|

Morning Advertiser, Monday 8 August 1831.

JAMES JARRATT, (successor to J. Boncey,)

WINE and SPIRIT-MERCHANT, "Liverpool Arms," Margate,

respectfully

begs to inform the Inhabitants, and Visitors of Margate, and

its vicinity, that he has newly fitted up the above House with every

accommodation, and assures those who may honour him with

their favours, that they may rely on the strictest attention, and

every article on the most reasonable terms. Wines of the best

Vintage,

Genuine Spirits equal to any in the Isle of Thanet, at the lowest

prices. Good Beds and Sitting-rooms for the accommodation of

Visitors. Coaches to Ramsgate ever hour, and to Sandwich, Deal, and

Dovor, every morning at eight, and afternoon at four o’clock.

|

|

From the Kentish Gazette, 13 November 1838.

DEATH.

At Margate, Mr. Jarrett, landlord of the "Liverpool Arms Inn."

|

|

Kentish Gazette, 11 January 1876.

SUSPECTED BRUTAL MURDER AT MARGATE.

Much excitement was occasioned on Sunday last in Margate and the

neighbourhood, by the report that a woman had been most brutally

murdered near the town on the previous night, by a man named Thomas

Fordred, who has been leading a kind of vagabond life for some time

past, often making his appearance before the magistrates on charges

of violence and dishonesty. The victim of what there is too much

reason to believe is a very shocking crime, was an unfortunate woman

named Mary Ann Bridger, who has been living with Fordred for some

time, holding to him in all the vicissitudes of his irregular life,

and sharing his lot through good and evil report. She was 27 years

of age, and her parents, who reside in Margate, are poor but

respectable. The accused man is 41 years of age, and a very sullen

and determined appearance. He is a native of Margate, and has

formerly been in the army. The particulars of the sad occurrence,

as far as they have at present been divulged will be found in the

evidence, taken before the Cinque Ports magistrates at Margate,

yesterday (Monday) morning.

The Magistrates upon the Bench were:- G. E. Hannam, Esq.,

(chairman), H. B. Sheridan, Esq. M.P., K. W. Wilkie, Esq., W. H.

Thornton, Esq., Captain Swinford, and Captain Hatfield.

The prisoner, who had a very callous expression of countenance, was

charged with the wilful murder of Mary Ann Bridger, in the parish of

St. John, Margate. He was not professionally represented.

Superintendent Compton, of the Margate Borough police stated:- On

Saturday night about twenty minutes past eleven, from what

police-constable Stockbridge told me I came to the station. I found

the prisoner there. At one o'clock in the morning of Sunday the

prisoner made this statement to me voluntarily:- "I came into town

at ten minutes past five. I met Mary Ann Bridger and gave her two

half-crowns to pay Mr. Payn, and she had 4 1/2d change out. I took

her to Mr. Austen's in the "New Inn" yard, and had a quart of beer.

She went to Mr. Pamphlett's pork butcher, and bought three pounds of

pork, and brought it to me at Mr. Jezzard's. There I had two 1/2

quarterns of rum and one glass. I went from there to Mr. Jarrett's the

"Liverpool Arms." Mary Ann Bridger, her father and mother, were

there. We had, say two 2 1/2 quarterns of rum. I went there to Mr.

Payn's and got my grocery for the week. From there I was going to

Salmstone. When I came to the bridge she fell down. I pulled her up

and she fell down again. I went and called the waggoner. I told him

I should go to the police and give information that she was dead."

Compton continued:- I went to the barn shortly afterwards

accompanied by Dr, Crawshaw. I found the body of Mary Ann Bridger,

whom I know well, dead, covered with straw. When I took away the

straw, she was naked, with the exception of her stockings. Her age

is 27 years. I came back to the Police-station at five o'clock in

the morning, and charged the prisoner with murdering Mary Ann

Bridger. He said:- "I am not guilty." I took off his

gabardine

(produced) the front of which is covered with blood. His jacket was

also covered with blood. I took his boots off, and the doctor will

give evidence as to their state. I searched prisoner and found on

him a razor, knife, and 9d. in money.

The prisoner said the Superintendent's statement was quite correct,

and he had no questions to ask.

George Emptage, waggoner, said:- The prisoner came to me between ten

and eleven o'clock on Saturday night. I went with him, and found the

deceased Bridger lying on the bank, with her mouth open and her eyes

half shut. I did not hear her speak. I did not see any blood. I

helped to get her on to the back of the prisoner, who carried her.

She was very near naked. I cannot swear whether she was dead or

alive. When I went away from him the prisoner said he thought she

was dead. When prisoner first came to me I noticed blood on his face

and on his coat which he was then wearing.

In reply to the Bench, Mr. Treves, F.R.C.S., said he has seen the

body of the deceased, and was of opinion that death resulted from

violence, but could not tell the exact cause without a post-mortem

examination. On the application of Superintendent Stokes, the Bench

remanded the prisoner till Saturday.

W. H. Payn, Esq., coroner for Dover and its liberties opened an

inquest upon the body of the unfortunate woman at three

o'clock yesterday afternoon at Salmstone Grange and adjourned to

Thursday.

|

|

Kentish Gazette, 18 January 1876.

THE SUSPECTED MURDERAT MARGATE ADJOURNED INQUEST.

The adjourned inquest was held at Salmstone Grange Farm on

Thursday afternoon last, before W. H. Payne, Esq. The first witness

called was Mr. W. K. Treves, F.R.C.S., who deposed as follows:- I

made a post-mortem examination of the body of the deceased Mary Ann

Bridger, and found numerous bruises on the face and bruises on the

collar bone, below the left breast, and on the lower part of the

abdomen. I also found bruises and scratches corresponding in their

appearance to those on the upper part of the chest. I found the

muscles under the bruise on the collar bone torn and pulpified. There

were also bruises on the front of the legs and on the back. On

opening the skull I fund the blood vessels belonging to the

membranes of the brain gorged with blood. The brain was otherwise

healthy. I examined the wind-pipe and throat, and found those

parts uninjured. I opened the chest and found the lungs and heart

healthy. On examining the abdominal cavity I found the membrane

covering the bowels, which is called the peritoneum, bruised in two

places, and blood poured out. In one of these places this membrane

was torn. The other organs were healthy. I consider these combined

injuries sufficient to cause death by shock, and I consider also

that all the injuries, except some of the busies on the face, are

such as might be reduced by kicking. The cold weather might have

been an accelerating cause.

My opinion is that death resulted from those injuries I have

described, and that those injuries were produced by kicks.

Mary Sheaf, wife of Henry Sheaf, a labourer, living at Chapel

Bottom, in the parish of St. John, said:- On Saturday night last I

was returning from Margate, between eight and nine o'clock, perhaps

nearer nine, when I heard a voice near the railway bridge, this side

of it. I came under Tivoli Bridge, and proceeded to the top of the

hill on my way home, when as I got to the top of the hill on my way

home, when as I got to the top of the hill I heard swearing. I was

then standing at the cross roads, at the corner of Salmstone Farm

meadow, when I heard the voice of a man a short distance off say

"You ______ I will do for you." I heard nothing else, but at once

proceeded on my road home to Chapel Bottom.

This being all the evidence, the Coroner proceeded to sum it up to

the jury, after having read the evidence to them. He reminded the

jury that it was simply their duty to enquire when, how, and by what

means the deceased woman Mary Ann Bridger came to her death. They

had heard the evidence of the medical man as to the injuries, and

that of the policeman, who saw Fordred and the deceased out of the

town. The constable said that they were purchasing goods, and that

both were intoxicated at the time. If the jury thought this Thomas

Fordred in coming home suddenly had a quarrel with the woman it was

for them to say whether he was the person who inflicted the injuries

on the deceased. They seemed, according to the description given by

the doctor, to be very brutal injuries, and quite sufficient to

produce death. Their duty was very simple, and it would be for

another court to settle the matter.

The room was cleared for the jury to consult in private, and after

about half-an-hour the Coroner and the public were readmitted, and

the following was announced as the verdict the just had arrived at:-

"That the deceased Mary Ann Bridger died from injuries inflicted

upon her by Thomas Fordred, and that the said Thomas Fordred is

guilty of the manslaughter of the said Mary Ann Bridger." The

Coroner then made out his warrant for the commitment of the prisoner

Thomas Fordred to take his trial at the assizes at Maidstone on a

charge of manslaughter.

At the Town Hall, Margate, on Saturday, Thomas Fordred was brought

up, on remand, on the charge of murdering a woman named Mary Ann

Bridger, with whom he had lived for some time past. The evidence

given by Superintendent Compton on Monday, which contained a

statement made by Fordred on giving information to the police of the

death of the woman, was to the effect that she received the injuries

which caused her death by repeated falls on the stony road, having

been read, George Emptage, a waggoner employed on the farm at

Salmstone Grange, said he was called by the prisoner between ten and

eleven on Saturday night week to assist in carrying the deceased to

a barn on the Grange. He believed she was dead when taken to the

police-station, and informed him the Bridger had met with her death

by repeated falls on the road leading to Salmstone. He caused him to

be detained, and sent for the Superintendent of police (Mr.

Compton), who, on Sunday morning, charged Fordred with the murder of

the woman.

Ann Emptage, the waggoner's wife, deposed that between ten and

eleven on Saturday night, while sitting in her room she heard some

one open a door; but as she supposed it was her husband, she did not

go out. After about three minutes had elapsed, however, she lighted a

candle and went to see what was the matter. She found that some

clothes, similar to those which had been worn by the deceased, were

lying in the washhouse, and also a pudding and some pork. The

prisoner then went to her husband, and later in the night they

returned together to the farm, with what she subsequently found was

the body of the deceased.

Thomas Richard Fuller, a labourer, said that at ten minutes past

eleven he saw the prisoner, who had apparently just returned from

Shalmstone Grange, and noticed that he had some blood on his left

ear. He told him that he was going to inform the police that Bridger

was dead, that she had killed herself by falling about on the road.

William Crump, a coalman, deposed that he was in the

"Liverpool Arms"

at about eight o'clock on Saturday evening. The prisoner and Bridger

were drinking there. Fordred threatened her that if he saw her with

any other men he would knock his brains out and hers also. He also

stated that while there he heard Fordred call the woman his "Daisy,"

"old dear," and used other endearing names.

Police-constable Bradley said that when he was the prisoner and the

woman immediately after they left the previous witness they were

both drunk. he walked with them some distance towards Salmstone

Grange.

Police-constable Bradley said that when he saw the prisoner and the

women immediately after they left the previous witness they were

both drunk. He walked with them some distance towards Salmstone

Grange.

William Brenchley Nash, labourer, said that soon after the previous

witness left the parties he saw the prisoner catch hold of the

woman's clothes and pull her off the path.

Mary Sheaff stated that between eight and nine she was about 100

yards from where it is supposed the deceased met with her death. She

heard a man say, "I will do for you." he appeared to be in a great

rage at the time.

Instructing-constable Stewert, K.C.C., deposed to receiving certain

things from Mrs. Emptage, among them being a broken dish in which

the pudding had been placed on the previous day. It was wrapped in a

handkerchief which was saturated with blood.

Mr. Treves, surgeon, fully described the injuries deceased had

received. he pointed out that great violence had been used, and that

the injuries must have been made by some blunt instrument.

Mr. Treves, surgeon, fully described the injuries deceased had

received. he pointed out that great violence had been used, and that

the injuries must have been made by some blunt instrument.

Other evidence having been given the bench retired for deliberation,

and after an absence of about ten minutes returned into court.

The prisoner was formally charged, and made as statement

substantially the same as the one he made to the police, adding that

his motive for taking her from the left-hand side of the road to the

other was because he thought if he placed her on the high ground he

might get her on his back and carry her to the barn.

The prisoner was then committed for trial at the next Maidstone

Assizes on the charge of murder.

|

|

Kentish Gazette, 21 March 1876.

WEDNESDAY. THE MURDER AT MARGATE.

Before Lord Chief Justice Coleridge.

The whole of the day was occupied up to a late hour with the trial

for murder, in the case of shocking violence to a woman, in which

Lord Coleridge, in a charge of remarkable power, told the jury

distinctly that if they believes the case for the prosecution they

were bound to find a verdict of wilful murder, a verdict which they,

after conviction returned.

Thomas Fordred, a man 48 years of age, was indicted for the wilful

murder of Mary Ann Bridger, at St. John the Baptist, Thanet, on the

8th of January last. He was also charged in the Coroner's

inquisition with manslaughter, but he was tried on the indictment of

murder.

Mr. F. J. Smith and Mr. Avery were for the prosecution; Mr.

Bargreave Deane, at the desire of the Judge, defended the prisoner.

The deceased was a young woman, who lived with her mother at Margate,

and who had from time to time cohabited with the prisoner. He had no

fixed residence, and at times she used to meet him at a farm called

Salmstone Farm, a little out of Margate, and to sleep at a barn

there. At 5 o'clock on the evening of the 8th of January last she

left her mother's house to meet the man. Between 7 and 8 o'clock

they were seen at a shop, and shortly afterwards they were seen again

going out of the town towards the farm. A few minutes afterwards a

witness who passed them in a cart was the man pull the woman off the

pathway. Between 8 and 9 a woman passing along the road near the

meeting of five roads, heard the voice of a man in an angry

threatening tone, and she heard the words, "I'll do for you." No

more was seen or heard of them, until after the woman's death, which

was caused, it was clear, by the violence of some one, between the

spot where they were thus seen and a spot further on, where the body

was found. About 450 ft. from the meeting of the five roads is the

barn belonging to the Salmstone Farm, where a wagonner and his wife

named Emtptage (who knew the woman from seeing here about there)

lived. Mrs. Emptage hearing some on about the premises, and observed

blood upon his coat and face. It was a moonlight night, and she could

see him clearly. The man asked her husband to come with him to help

him to pick up his Poll, who he had left in the road, he said, and

who had killed herself. Emptage went and found the body of the woman

lying by the side of the road, quite dead, in a pool of blood, her

clothes torn off her back, the road for a space of nine yards being

covered with blood and showing evident signs of terrible struggle,

and the face and body showing marks of shocking violence. The body

was almost naked; it had hardly anything on except the stockings;

her clothes being literally torn off her back. The prisoner made

statements to the effect that the woman had killed herself by

throwing herself about when drunk, and this account he said he gave

because he knew the police would be sure to come after him on

account of his having been seen with the woman and blood being upon

his dress. The surgical evidence showed that the woman had sustained

many serious wounds, apparently from kicks. There were several

wounds on the shoulder and the chest, and two marks of kicks upon the

abdomen, with scratches upon the skin (apparently showing that the

body was bare when the kicks ere given), and these blows had caused

ruptures. It was observed that though there were no marks on the

palms of the hands, the backs of the hands were injured as if by

being stamped on. Some hair was found on the spot, which

corresponded

with the woman's. The prisoner's dress and boots were found stained

with blood, and when he was first seen there was blood on his face.

Upon being apprehended, he repeated his statement that the woman had

killed herself by falling about, and that the tearing off her

dress was caused by the efforts to lift her up.

Mr. F. E. Smith, in opening the case for the prosecution, said it

would be for the jury to consider whether there was an atom of truth

in the statements of the prisoner, and whether they were consistent

with the actual facts which would be proved.

On the evidence being begun, one of the jurors said he was unwell

and begged to be excused. He was, he said "nervous" and

subject to

fits, and he had better withdraw at once.

Lord Coleridge upon this directed the juror to withdraw, discharged

the jury, and directed a new jury to be empanelled, allowing the

prisoner his challenges anew. In fact, the old jury were

re-empanelled with the exception of the juror withdrawn, for whom

another was submitted who had heard the case stated, and the trial

then proceeded the first witness not having yet been examined.

Lord Coleridge, in summing up the case to the jury, said it was in

truth an issue of life and death; for upon their verdict it depended

whether the prisoner should be left for a few years longer to pursue

such a life as he might be able to pursue on the face of God's earth,

or whether his life should be cut short by an ignominious death. But

serious as the issue was, they must determine as they would any

other, on the effect of the evidence on their minds. If they were

convinced that the terrible guilt of the crime charged against this

man was brought home to him they must not shrink from saying so, but

f not satisfied of it then they must acquit him of that guilt. They

must not jump to conclusions, or substitute surmise for evidence,

but they must act upon their conviction on the evidence. That the

deceased woman died in the company of the prisoner was clear; that

she died by violence was clear. Did she die through violence

wilfully inflicted by the prisoner? That was the great question in

the case. The deceased woman had been the mistress of the prisoner,

and on this night they were together. The gown the woman wore was

not produced, and had not been found. The mother saw the woman at

half-past 4, and said she was quite sober, and witnesses who saw

them going out of the town, said they seemed drunk, and spoke to

give impressions which indicated that they had had former quarrels.

At a quarter-past 8 they were seen by a witness who spoke to the man

using an angry expression and pulling her off the path, and he said

they were not reeling, and this witness was the last person who met

them together - the last person who saw the woman alive. The next

witness was the woman who, about a quarter to 9, heard the voice of

a man in the road near the place exclaiming, "I'll do for you," and

heard the sound of scuffling. That was the only time when the

prosecution suggested that the deadly attack commenced. It might be

so certainly, but it might not be so, and there was nothing in the

nature of the evidence to point to the inference that it was the

prisoner who was heard. But then came other evidence that it was the

prisoner who was heard. But then came the other evidence which

presented the most important part of the case, the evidence of the

Waggoner and his wife, and the police. Some one about half-past 10

brought to the Waggoner's door some clothes which were part of the

clothes which the poor woman had worn. But for the statements made

by the prisoner three times over, his counsel might have statements

made it clear that he must have brought them, for he admitted that

the woman met her death in his company, and that in his company her

clothes came off, and no one was present but he, so that the

conclusion was inevitable that he was the person who brought them.

What effect that had upon the mind with reference to the account he

gave? The poor woman was lying naked and dead on the snow in a lane,

and the first thing he does is to gather up the outside premises of

the cottage. Then the prisoner carried the dead body all the way to

the barn and did not (the witness said) reel more than a little. If

that were so, then it was vain to contend that he was in such a

state of drink as not to be able to commit the act of violence

attributed to him. There was also blood upon his face and dress.

That was one of the most serious parts of the case against the

prisoner. He was the only person with her person. He was capable of

carrying her; was he not capable of killing her? Did he kill her?

What would be the natural conduct of a person who had no hand in her

death? What was the language the prisoner used in speaking of the

shocking event? He might be destitute of the ordinary feelings of

humanity, and yet not guilty of murder. There was blood upon him,

and the policeman at once asked if there was blood upon his hands. He

would not comment upon the language used by the prisoner, and after

all there came the one "touch of nature." "I found she was cold and

dead. I kissed her lips and left her." There was the account which

fixed him with being present at the time of her death, and the jury

must judge what construction they put upon such conduct and such

language. The witness who saw him at this time said that, though he

had been drinking, yet at that time he was not withstanding when it

was suggested that he was so drunk that he did not know what he was

about. He was capable of making that long statement - of the truth

or credibility of which the jury must judge.

Mr. Deane interposed to observe that his argument had been, not that

the prisoner was to drunk to know what he was about, but that he was

too drunk to have the deliberate intent to kill.

Lord Coleridge, however, as to that, said he must as that it was not

material, assuming that the prisoner committed these acts of

violence. The prisoner, be it observed, had made four different

statements, and one of them was written down from his lips and

signed by him. Anything more deliberate - true or false- never was

done. And the jury must judge whether the state of drunkenness

suggested was consistent with such clear, deliberate statements.

Then as to the truth of falsehood of these statements, they must

contrast the account given by the prisoner with the account of the

poor woman's state as detailed by the doctor. She sell down, he

said, twice or thrice; that is all; not a word as to falling o her

knees, as had been suggested. Then there were the undoubted facts

that the woman died in the presence and with the injuries described

by the witnesses, and especially the doctor. There were two large

wounds on the back of the head into which the witness could put his

finger. There were marks of nails (of boots) on her chest. There

were other injuries discovered, more particularly by the doctor. The

body was naked; there was a wound on the right temple and another

over the eyebrow, the lip cut open, and teeth loosened; two scalp

wounds on the back of the head two inches in diameter; all the wounds

of a bruised and jagged character. "The hands were bruised on the

back, but no injury on the palms - it looked as if the hands had

been trodden upon." That was most remarkable and deserving of

serious attention. On a post-mortem examination there were found

other injuries, which the doctor described. It must have been great

violence, he said, to have caused the injuries. They seemed to be

caused by a thick boot, with large nails; they could not have been

caused by a fall; it would have been required great violence to cut

the lip and loosen the teeth. There were bruises below the breast

and on the hip and thighs and on the front of the legs; there were

ruptures in the abdomen, arising from the blows which caused the

bruises. Such injuries, he said, could not have been caused only by

falling down. Now, it was for the jury to compare this state of the

body and the aspect of the spot where it was found with the account

given by the prisoner. There were the marks upon the spot - he would

not say of a struggle - but of moving about; and the witnesses said

there were marks of blood, and one witness said "pools of blood."

When the prisoner brought the body it was dead - she had been lying

there long enough to bleed so much as to leave behind "pools of

blood," and the account given by the prisoner was that she fell

down

two or three times. The jury must judge for themselves whether this

was true. There were no limits to the range of possibilities, but the

jury were bound to act on the reasonable result of the evidence

before them. Was it reasonably possibly that the wounds could be

caused by falling down twice or thrice on the road - wounds in the

head large enough to put the fingers in, rupture of the abdomen,

bruises and wounds all over the body, the clothes torn off the back,

and all this caused by two or three falls? Such was the story the

jury were asked to believe. But they must proceed upon principles of

common sense and not substitute surmises for the result of evidence.

Probabilities were necessarily acted upon the affairs of life, and

the question was whether here there was not a strong moral reality

that the prisoner was guilty of the crime charges. It had been

suggested that they should find a verdict of manslaughter; but the

prisoner had never suggested that was necessary to grant such a

verdict upon. He had never suggested a quarrel and a fight; and he

was bound to say that, in his view, the only verdict for them were

the first and the third - wilful murder or not guilty. If they

believed the prisoner's story then he was not guilty; if they did

not believe it, then he was guilty of wilful murder. gentlemen (said

his Lordship in conclusion), the case is of immense importance. To

the prisoner, of course, it is of immense importance - it is an

issue of life or death. But to me, I confess, greater importance as

affecting the integrity of trial by jury, and the trust we must all

of us put in the absolute faith and honour of the 12 men to whom the

Constitution in trusts in cases of this kind the decision of these

dread issues. To you I leave this issue, reminding you again that

you have a solemn duty to perform, and I have confidence that you

will perform it.

The jury at six o'clock retired to consider their verdict, and after

an absence of about a quarter of an hour returned into court with a

verdict of "guilty."

The prisoner being called upon to say why sentence of death should

not be passed upon him, said he had nothing to say.

Lord Coleridge then proceeded to press upon him in most impressive

terms the last dread sentence of the law. He said:- You have been

found guilty, after a careful and patient trial, of the greatest

crime of which a human being is capable, and for that not I, but the

law, through me, says that you must die. I will use but the simplest

and shortest and fewest words I can. It is no part of my duty to add

to the terror and the misery which must now invest you. You took the

life of one to whom you were bound by ties of the closest relations;

you took it cruelly, savagely, and without pity and without remorse.

You sent her unmercifully from this world to another. The law is more

merciful to you than you were to your victim. How you may stand with

that ineffable Being before whom we must all one day appear it is

not for me to imagine or suggest. To Him and to His infinite mercy I

must now leave you. I have to pass upon the sentence of the law,

which is, that you be taken to a place of execution and there hanged

by the neck until you are dead, and may Almighty God have mercy on

your soul!

|

|

|

Above amalgamation of photos kindly sent by Debi Birkin. |

LICENSEE LIST

BONCEY John 1823-26+

JARRATT James 1831-Nov/38 dec'd

JARRATT Ann 1839-51+ (age 60 in 1851 ) )

JARRATT Charles 1858-76+ (age 41 in 1871 ) )

GRANT Alfred 1881-82+ (age 24 in 1881 ) )

TAYLOR Albert Edward 1890+

DEVERSON Alfred J 1891+ (age 31 in 1891 ) )

WOODWARD Leonard 1901-03+ (age 26 in 1901 )

("Liverpool Inn") )

("Liverpool Inn")

HICKSON Louisa Harriett 1911+ (age 52 in 1911 ) )

RILEY George 1913+

HOLMAN Walter Freeman 1922+

LODER George 1930+

STEAD P E 1938+

https://pubwiki.co.uk/LiverpoolArms.shtml

http://www.closedpubs.co.uk/liverpoolarms.html

From the Pigot's Directory 1832-33-34 From the Pigot's Directory 1832-33-34

From the Kelly's Directory 1903 From the Kelly's Directory 1903

Census Census

From

Isle of Thanet Williams Directory 1849 From

Isle of Thanet Williams Directory 1849

|