|

From the Deal, Walmer, and Sandwich Mercury,

16 June, 1900. 1d.

THE CHARGE OF FRAUD AT SANDWICH

THE PRISONERS SENTENCED

At the Sandwich Petty Session on Monday, before the mayor, Alderman

Watts and Lass, and Mr. H. Maurice Page, Herbert Ernest Adams, who

described himself as a publication agent, of London, and Frederick John

Gale, described as an historical writer, both of very respectable

appearance, were charged on remand with unlawfully obtaining the sum of

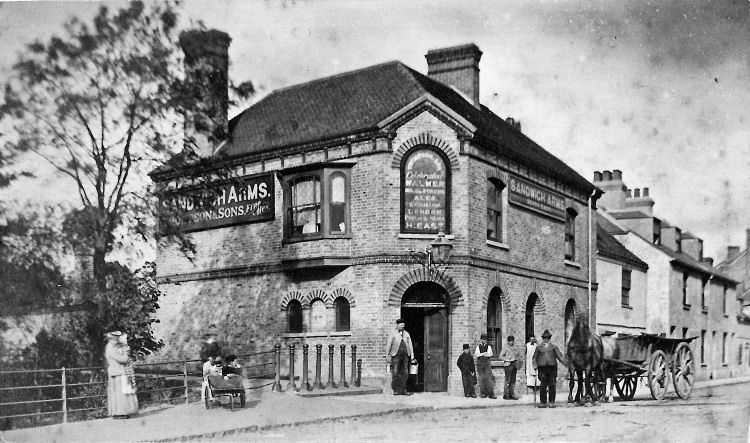

£1 from Joseph Monck, of the "Sandwich Arms," on the 5th inst., under

false pretences, with intent to cheat and defraud.

Dr. Hardman said he appeared to prosecute in this case on behalf of

Mr. Monck. As some of the Magistrates were not present when the case was

formerly before the Court, he would give a few details of the facts. On

the 5th June, the two prisoners came several times to the "Sandwich

Arms," kept by Mr. Monck, and on the last occasion, about 8.30 in the

evening, the elder prisoner who gave his name as Gale, informed Mr.

Monck that he had telegraphed and telephoned to his firm, said to be the

East Kent Coal Company Limited, but he could not find them in, and he

supposed they had gone mad over the capture of Pretoria, and that was

why they were away. he said he had no doubt he would hear from them in

the morning, when he would have as much money as he required. The

younger prisoner, who now gave the name of Adams, but at that time gave

the name of Williamson, then produced a bill of exchanges, apparently

drawn on bill paper, duly stamped, and asked for a sum of money to be

given upon it, either the whole or part of the amount stated. The bill

was dated "Dover, 17th June," and was for £4 17s. 6d. sterling, wages

and expenses account, in favour of Mr. Frank J. Williamson, and was

drawn on the East Kent Coal Company, Limited, of 171, Queen Victoria

Street, London, E.C.; it had his acceptance written across it, and was

payable at the London and County Bank, Holborn, on the East Kent Coal

Company's account. Mr. Monck did not care about advancing money to

strangers, and at first refused to have anything to do with it, but

ultimately was induced to part with £1 on the security of the document,

which was left with him, and at his request the younger prisoner wrote

his name, F. J. Williamson, on the back, and that no doubt was the Frank

J. Williamson mentioned in the bill. They promised to go in the morning

and settle, but Mr. Monck did not hear anything more of them.

Consequently he gave information to the police, and they were

subsequently arrested at Deal. The elder prisoner, when arrested, said,

"You have made a mistake; I know nothing about it;" but the evidence

would satisfy the Bench that he took an active part in the negotiations,

and although the other man produced the bill, it was done by the two

jointly. There was a decided case, the Queen v. Young, which provided

that where several persons were present, and were present and were

acting together in the process of the fraudulent purpose, there was an

obtaining by all. he should call another person who was in the bar at

the time, a witness from the office of the Registrar of Joint Stock

Companies, to prove that no such Company as the East Kent Coal Company,

Limited, had been registered in England, and he should also produce

evidence that the same afternoon, but prior to this occurrence, the

prisoner took the same bill to Mr. Waters, at the "Market

Inn," and attempted to obtain money from him in the same way. There

were cases to show that attempts made previous to the offence charged

were admissible in evidence in order to prove a guilty knowledge of the

persons tendering these documents. It was necessary in cases of false

pretences that there must be statements of some pretending existing

fact, made for the purpose of inducing the prosecutor to part with his

money, and it must also be shown that the prosecutor parted with his

property by reason of the false pretences. Mr. Monck would satisfy the

Bench on this point. It would be obvious to the Magistrates that there

were in this case a number of false pretences in the existing alleged

facts. The bill purported to be valid and negotiable, there was the

pretence that the prisoner had the authority of a certain firm to draw

and negotiate it, and that the money was due to him from them, that the

Company was in existence, and had a registered office at 171, Queen

Victoria Street; there was also the pretence that the prisoner Adams was

the person Frank J. Williamson mentioned in the bill. Under a recent

statute, the Magistrates had the power to legal summarily with prisoners

in certain cases of false pretences, but he ventured to suggest, with

great respect, that this was a case in which their summary jurisdiction

could not be exercised. The amount was not a large one, but the manner

in which it was obtained showed that the prisoners were acting upon a

system. It was a form of fraud that was peculiar liable to be repeated,

and it was desirable that there should be some time between the

committal and the trial in order that proper inquiries might be made

with a view to finding out previous transactions of the prisoners in

other matters of this kind.

The Mayor said that if Dr. Hardman would confine himself to the case,

the Bench would deal with that point. They were quite aware of all the

advantages, and it was only wasting their time to go into that.

Dr. Hardman: If you please, sir.

The evidence of Mr. Monck, taken at the previous hearing was read

over, and further examined by Dr. Hardman, prosecutor said: At the time

he parted with his money he quite believed the bill tendered to him was

a valuable security for £4 17s. 6d., or he would not have parted with

his money. It was on the strength of the bill being handed over to him

that he parted with his money. He believed the verbal statement made by

the prisoner; it was a plausible story, and he thought it was correct.

By Gale: They came into the house in the morning together, and had a

few drinks. That was the first he saw of them. Towards mid-day they came

in again. They came together three times, and on the first two occasions

they did not ask for anything. On the third occasion Gale did sit down

in the public bar, and Adams went forward and leant over the bar, but

previous to that Gale made a statement. (Gale: That I will explain, I

had been to the telegraph office to send a telegram from Adams to his

firm). Gale said he had been to the telegraph office, but he did not say

for whom. But previous to that he went out, leaving a small brown paper

parcel in his (prosecutor's) charge, saying "Take care of that; that is

worth £1,000 to me." He took charge of it, and the prisoner soon

returned. Adams then came up to him, offered him a piece of paper, and

asked him if he would give him the money on this order. He said "No,"

and then Adams asked him if he would give him £3 upon it. he again said

"No," and Adams then said, "Give me something on it; we will have our

money at the Post-office in the morning." gale was standing with Adams

at the bar, and there were others present. he had never seen the paper

in gales' possession. Gale was cognizant of the whole thing. Adams

turned to gale, and said, "You have heard what he says; he cannot give

us the money."

Adams: This man has nothing to do with me.

Gale: I wish to show that I know nothing about the paper being in his

possession, not have I seen it, and I did not ask the landlord for

anything. I wish to show that I have had nothing to do with this

transaction. Prisoner is a stranger to me. I have met him on two

different occasions previously, quite by accident.

Henry Dilnott deposed that he was in the private bar of the "Sandwich

Arms" on the 5th inst., about 8.30 in the evening, and saw the two

prisoners there. They were in the public bar. He heard them getting the

change for this note, but thought that Mr. Monck knew them, till the

next morning, when he was told different. Mr. Monck gave them £1 on the

note, and Adams said, "I shall be having the money in the morning, and

will give you the full amount." He heard Adams ask Mr. Monck for money,

he believed it was 30s., on this note. Gale said he had been to the

telegraph office and the telephone, and had been to the station for the

money, and could not get any reply. (Gale: I had been to the Post-office

for him.) Witness saw the document handed to Mr. Monck; it was similar

to the one produced. Mr. Monck just looked at it before handing over the

money. Gale told Mr. Monck his friend would come and see it paid.

By Gale: He (witness) was sitting opposite the door in the

bar-parlour, and could see right into the bar. The door was open all the

time.

By Gale: Mr. Monck gave Adams, and not "them" the money. he did not

see the document in his (Gale's) hands at any time, but he heard him

tell Mr. Monck he should have the full amount in the morning.

Gale: After the money was paid, I said I believed the thing to be

right, and if Adams did not pay I would see that it was paid. I had

sufficient confidence in the man, and would have cashed it myself if i

could have spared it.

John Waters deposed that he kept the "Market

Inn" at Sandwich. The two prisoners came into his house on Tuesday,

the 5th inst., between two and three o'clock in the afternoon. They came

in as ordinary gentlemen, very good customers, and very jolly. A short

time afterwards the younger prisoner (Adams) asked him if he would cash

or advance him money on a note of hand. He handed witness a bill, or

whatever they might call it (the document produced), and asked him if he

could charge it. He told the prisoner his housekeeper would be down in a

short time, but that he did not do such business at that himself.

Prisoners left the bill in his possession, while they went to and from

the Post-office, and having no bank account, he took it to the spirit

merchants. He could not say whether they both left the house, as they

were joking and laughing, but witness took the bill away, and returned

with it; the spirit merchants' banking business was over, and they

advised him to try the bank in the morning. he told the prisoners he was

unable to do anything with it, and Adams then said it did not matter.

The elder prisoner did nothing in the matter; he was too busy

telegraphing and going to and fro. He would not be certain whether Gale

was present when Adams handed him the bill, but he was there when

witness brought it back.

Dr. Hardman: Did it seem to you that the other man was cognizant that

the money was being asked for on this bill?

Gale: Is that a privileged question - to ask a man's thoughts. Is

that evidence?

Dr. Hardman: It is a question of fact. Did what passed make it appear

to you that the elder prisoner knew money was being asked for on this

bill?

Witness: My conscience was perfectly clear that the two were one.

Dr. Hardman: Did what was said by the younger to the elder prisoner

make it clear to you that the elder one knew that money was being asked

for on this bill?

Witness: Yes, perfectly clear.

Dr. Hardman: That was the effect of the conversation?

Witness: Yes, sir.

By Adams: The prisoner gale was within three yards, and certainly

within hearing, when you asked for the money, and when I came back you

told him I could not do it. I don't say you both had your hands in one

pocket, but you were as close together as we are now, and I did not

whisper, neither did you.

By Gale: You did not individually ask me for money or anything.

Gale said he did not ask anyone for anything, and had not seen any

document. He was, he knew, slightly intoxicated, at the time, but he was

simply in the company of this man.

Arthur Elwin Taylor said he was a clerk in the office of the

Registrar of Joint Stock Companies. He had made a search in the Register

of Limited Liabilities Companies, under the Companies' Act, and there

was no such Company registered as the East Kent Coal Company, Limited,

of 171, Queen Victoria Street, London, E.C.

The evidence of Police-sergt. Curtis, taken at the last hearing, was

read over.

The Magistrates were in consultation, when the prisoner Gale said: I

should like to ask Mr. Monck a question. (Addressing prosecutor): If you

were with an acquaintance with whom you had only been in company two or

three days, and were out with him for the day, and that acquaintance

asked a person in a similar position to yourself as a publican; to cash

or advance money on an order that turned out to be wrong, would you

consider yourself to be liable for another man's act?

Mr. Monck: I have nothing to do with that. I will not answer the

question, as it has nothing to do with the matter. Your business and my

business is altogether different. What i would do and what you would do

are two different things.

prisoners elected to be dealt with summarily, and on being charged,

both pleaded not guilty.

Adams (addressing the Bench), said: I had the unfortunate coincidence

to meet a man in Maidstone about a month ago, who put me into this way

of making out these bills. You see I don't understand anything at all

about them. He said if I made out a bill at any time I was thrown upon

my resources, and got a tradesman to cash it, he would let me have a sum

of money on it, and on paying it into the Bank I could meet that bill,

and it was accommodation money. He gave me several of these bills at the

time, for which I gave him consideration in money. I had made this bill

out myself, and i had no intention whatever of defrauding Mr. Monck of

the money. My intentions were to re-fund it as soon as I had received it

from my firm. This gentleman, who was ignorant of the fact that I had

the bill, telegraphed for me, and I had full faith that I should receive

the money, and had I received it, I should have gone to Mr. Monck in the

morning, and paid him back. It did not come, and I thought that possibly

my people might not know the town I was in, and that knowing I had

business at Deal, and not thinking I was there, they had sent it on

there, and I went on to Deal to see if there was anything for me there,

but there was not. I made no false pretence whatever. I did not ask him

to lend me the whole sum, because i knew I could not afford to re-pay it

from the pay I had to come. I did use the name of a firm I did not know,

nor do I know whether there was any such firm in existence. There was no

attempt by me to cheat, defraud, or obtain money by false pretences. I

have no need of money. I have a living in my hands, and it is not

necessary for me to do anything in that way. I am a man who can get my

30s. a day when i am properly working, as I should have been if I could

have found my people at the office. When I took the money, I fully

believed that I should be in a position to re-pay it as I had stated. I

had nothing to do with this gentleman (Gale). Possibly it would have

been better for me if I had. He was not aware of what I was going to do,

and if I have to be mulcted in the matter myself, I am anxious that it

shall fall entirely on myself, and that anyone who happened to be with

me at the time will not suffer for anything I may have done. But I did

not intend to transgress myself in any shape or form, much less obtain

money by false pretences.

Gale made the following statement: I simply wish to say that during

the last three weeks there has been very little business doing with

commercial men - men who travel. There has been Mafeking day, Pretoria

Day, the Queen's Birthday, and one or two other very similar days, three

Sundays, and so forth, and if you get pleasuring one day, you are likely

to make it last a second day. I am rather a social man, and I happened

to meet this gentleman at an hotel I was staying at. We were talking to

one another, not having anything to do on these days, and found each

other very good company. I then lost sight of him, but we met again at

Ramsgate quite by accident, and we spent three-fourths of a day

together. I then came here, and we met by accident also - not by any

engagement, and we were together during this affair. I have never been

in any way inquisitive to know who are his friends or relations, nor has

he known mine. I know nothing about him, except from his own statement.

I have seen him, as I say, upon three different occasions within the

last three weeks, and because I happen to be in his society, and he does

this, I am detained with him. He certainly asked me if there was any

chance of my letting him have some money, but I said that I could not,

having been spending such a lot that I had exhausted myself. But I have

never asked anyone for money, I have never shown anyone any document,

and I have never handled one. He being in my company, to these gentlemen

in Sandwich it appears that I am with him, but according to the evidence

of Mr. Monck, who thinks he has lost the sovereign that he advanced, I

could see at once that it was a document he was handing over. But apart

from that, when we first arrived in Sandwich, Adams asked me to go to

the Post-office to telegraph for him to his firm for a sovereign. I

cannot give you the name of the telephone clerk, but he can be called,

and will verify what I say. he meant, I suppose, to pay the £1 he had

borrowed, and I felt sure he would get it. It was nothing to do with me;

I did it for Adams. That was early in the day. We liquored in two or

three houses, and the whole of the time we were in Sandwich we were

drinking, and I did say that if Mr. Monck advanced the sovereign, I felt

every confidence in this man. Having been in his company on past

occasions, I looked upon him as a man who would meet everything

honourable, and I never thought for a moment that there was anything

wrong, nor did I think he meant wrong. I made the remark that if he did

not pay I would, but it was after the act was done I said that. Mr.

Monck and the and the other gentleman have all stated on oath that they

never saw any document in my possession. I never asked for any money,

nor have I had any money pass into my hands. How can I be found guilty

because i happened to be in his company. Because one man happened to be

with another, he is not answerable for that man's actions. It has

already been a very great inconvenience and loss to me. Now that the

holidays are over, I have to recoup myself. I have had a lot of

unpleasantness, and I am as innocent as any gentlemen present. It is a

coincidence, but I have had to pay the penalty of it up to the present.

Supt. Chaney produced to the bench the following information he had

obtained from London and Margate:- The Margate police reported that

Adams stayed at 63, Dane Road for about a fortnight, with a Mr. R. Meyer

(a visitor from London), with whom he had just previously been lodging

at their London residence, 27, Borman Road, Tollington Park. It now

appeared that Mr. Meyer had been defrauded by him. On leaving Dane Road,

Adams went to the "Imperial Hotel," for a day or two, leaving without

paying on June 2nd, and he had not been seen at Margate since. Whilst at

the "Imperial," he obtained £3 from the manageress on the security of a

draft for £6 18s. which he represented was due to him as wages from A.

W. Innes and Co., 161, Upper Kensington Lane, S.E. This draft was

probably worthless, but as the manageress declined to prosecute, no

enquiries were made. Gale was seen about Margate with Adams, but nothing

was known of him.

The Metropolitan Police reported that the prisoner Adams resides at

24, Foxley Road, Brixton, in April last. he remained there about six

weeks, with a young lady who he represented as his sweetheart, occupying

separate rooms, and the landlady had difficulty in getting the rent,

which she did finally by threatening to call the police. he then went to

Tollingate Park, where he remained till April 27th, leaving to go to

Margate, being a month in arrears with his rent. During the time he was

residing in Brixton, he was employed by Messrs. A. W. Innes and Co.,

161, Upper Kensington Lane, S.E., as a traveller in laundry requisites,

to be paid on commission. At this place he obtained from his employer,

be means of bogus orders, about £20, but at present Mr. Innes had not

decided to prosecute. the firms given at 78 and 171, Queen Victoria

Street, were fictitious. prisoner had obtained a suit from a tailor in

Tolingate Park, and a gold watch from a jeweller in Walworth, which were

unpaid for. Enquiries at Scotland Yard elicited the fact that a man

named H. E. Adams, and somewhat answering to the description of one of

the prisoners, was in custody of the Governor of Kilmainham Prison in

July, 1899, on a charge of obtaining money by worthless cheques.

The mayor said there was no doubt in the minds of the Bench that the

prisoners were both guilty of this offence. They were together in both

public houses and in the first instance they attempted to carry out what

they were successful in accomplishing in the second. The sentence of the

Court was that they be imprisoned for two months with hard labour.

|