|

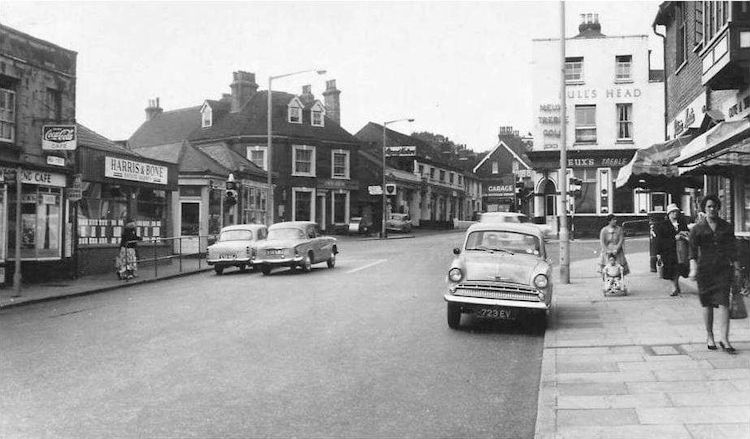

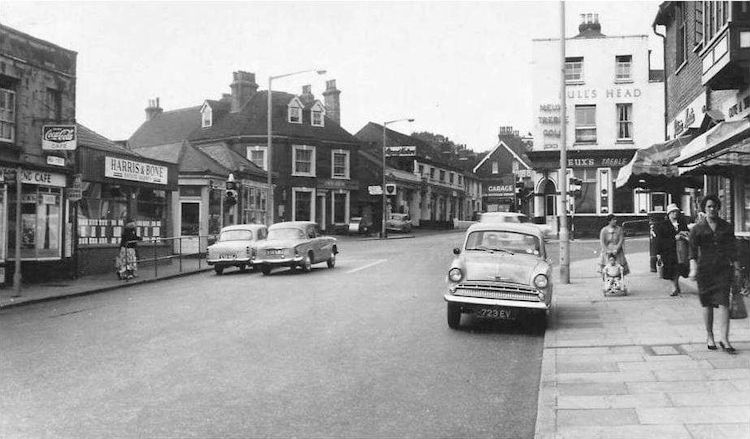

2 London Road / Gun Lane

Strood

Above photo 1870, by permission of

http://www.kenthistoryforum.co.uk. This original building was

demolished around about 1873 and replaced by another building that went

under the name of the "Mid Kent Hotel" but changed back to the "Bull"

again in 1946. |

Above photo, 1960. |

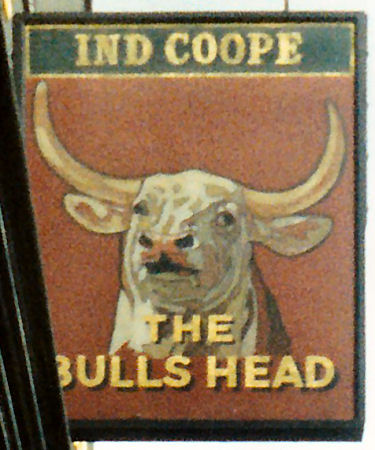

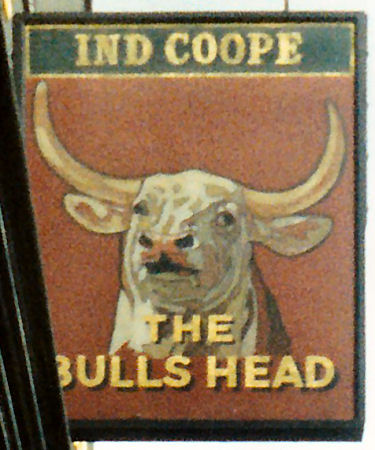

Above sign 1990.

With thanks from Brian Curtis

www.innsignsociety.com. |

Above image from Google, May 2012. |

Above photo, date unknown. |

Above image from Google, May 2014. |

In 1869-70 the pub was part of a consortium who were advertising their

goods of selling tea in response to grocers' selling beer and wine. (Click

for further details.)

Originally built in 1844 on the junction of Strood High Street and Gun

Lane, this was demolished in 1873 to be rebuilt as the "Mid

Kent" and that was later renamed as the "Bull."

http://www.kenthistoryforum.co.uk states that the original pub dated

1870 approx in the top photo was called the "Mid Kent Hotel" for a short

time. In actual fact Couchman's notes state:- "Mid Kent Hotel" (formerly

1844-1873 and again from 1946. The "Bull's Head Hotel") no. 2 London Road"

which I have confirmed as correct referring to Kellys and the census

returns. So it was the "Mid Kent Hotel" for 73 years.

The original was Bull Head Inn (no 's' so probably more grammatically

correct,) although Pigot's Directory of 1828 seems to have got the 's' back

again.

|

Kentish Weekly Post or Canterbury Journal 21 June 1822.

Lieutenant William Hopwood, on the half-pay of the Army, aged 35 years,

died suddenly in the street a short distance from the "Bull's Head," in

Strood, on Thursday, and was taken to the Workhouse. It appears he had

left his home, in King-street, Troy Town, in the morning, in apparent

health, for the purpose of taking a walk, and signified his intention of

returning with something for dinner. The deceased was subject to fits.

|

|

From

http://www.medwaymemories.co.uk From the Times, 21 January 1837.

How one pauper died: starving in Strood.

Premature death, disease, starvation, poverty. Contrary to the many

rosy tales of a better life in the past, not all was good. The lives of

many Medway people in the 19th century were tough and dull. In some

cases they were heart-wrenchingly appalling.

Take this inquest report, which I found in The Times newspaper of 21

January, 1837. It is a tragic tale of a trader with connections among

the highest in the land who fell on times. How, we shall never know, for

he took his secret to a pauper's grave. The narrative style of the

report cannot disguise the awful facts. Here was a man who, at the

height of the Industrial Revolution, starved to death in Strood.

The inquest, by Rochester coroner Mr Patten, was held in the

boardroom of the North Aylesford Union workhouse, Strood. The dead man

was Thomas Burton, said to be aged about 65.

First to give evidence was Charles Dean, watchman for the parish of

Strood. “On Sunday night last, about half-past 11 o'clock, I was told by

a coachman of one of the Dover coaches that a person was lying in the

road, and was in danger being run over,” he said.

“I went up Strood Hill and met [Burton] coming down. He staggered in

his walk, and I thought he was intoxicated. I led him part of the way

down the hill. I asked turn where he was going; he said, to Strood; he

had come from Cobham.”

THOMAS BURTON WAS FIRST TAKEN TO THE BULL'S HEAD

The watchman then left him, but later found Burton lying in the road

again, so he and a colleague took him to the stables of the nearby

"Bull's Head," where they made him warm in the straw.

Burton's condition, however, was deteriorating and James Vine,

relieving officer of the union workhouse, was called. At first, Vine

said, he thought Burton was drunk, but soon changed his mind. This man

was terribly ill and he agreed to move him into the workhouse.

A medical man also attended. Robert Rogers — his role is unclear, but

he appears to have been a doctor's assistant — told the inquest: “I gave

directions that he was to be put into a warm bed, and to have a pint of

strong beef tea, and a tablespoonful of brandy every two hours, and not

to be put into a warm bath, or anything done which was likely to exhaust

him.”

Vine added: “I rang up … and procured the workhouse chair.” (In these

pre-telephone days, Vine must have meant that he rang a bell and issued

orders). “He was then removed to the workhouse, where every attention

was paid to him.”

A wash – but why on earth didn't they feed him?

But it was not enough, as an inmate, Susannah Hayler, explained. She

said: “Early on Monday morning last the deceased was brought. He was in

a very filthy state and I was employed to wash him. I used warm water. I

had washed his face and neck, and while washing his arms he died. He did

not speak at all.”

Joshua Hunt, master of the workhouse, added: “We placed him by the

fire in the hall, and I was ordered to get him some brandy-and-water and

some gruel; in the meantime he was being washed, and died in about half

an hour after his admission. There was no money found on his person.”

A pocket-book, however, was found in his hat. It contained “various

memoranda of the addresses of some of the nobility, and other persons of

high rank, to whom the deceased had applied for pecuniary assistance”.

Among the papers was a card for Thomas Burton, timber merchant, some

pawnbrokers' tickets, pledged in London, an account of timber cut on an

estate in 1787, and a letter from Lord Cornwallis: “For the last time,”

it said, “you may call upon Messrs Hoare's [presumably his lordship's

legal representatives] for a sovereign.”

Another envelope, although found without letter, came from the Earl

of Jersey. So this man indeed had connections in high places. But he

still starved to death.

The union's medical officer, William Stephenson, spelt out the

dreadful conclusion after conducting a post-mortem examination: “On

opening the chest I found the heart, lungs and every other viscera of

the chest perfectly healthy — indeed unusually so for a person of the

deceased's age.

“The stomach was distended with air, but perfectly empty, there being

no particle of food in it, nor in the intestinal canal. I am of opinion

the deceased died from cold and starvation.”

Horrible, isn't it? |

|

Kent Herald, 6 February 1845.

Marriage.

Jan 27, at Strood, Mr. Isaac Pemble, butcher, of East Malling, to Miss Fanny

Trench, of the "Bull's Head Inn," Strood.

|

|

Maidstone Telegraph. 5 June 1869.

Robbery by a Youth.

Henry Wilson, a respectably dressed youth, was placed in the dock on a

charge of stealing three wheels, two springs, and an axle tree, part of

a perambulator, the property of Mr. Henry Tranah, landlord, of the

"Bulls Head Inn," Strood, on Wednesday, the 20th inst.

The prisoner's father appeared in court, and evidently felt his son's

condition deeply, as he had resided in the locality for the last 30

years, and bore a most respectable character.

Mrs. Hannah Tranah, wife of the prosecutor, said she saw the three

wheels, two springs, and axle tree produce, safe in the backyard of her

husband's premises on the previous Sunday or Monday. On Wednesday

morning she missed them. They were worth about 15s.

P.C. Fishlock, said he went to the prisoner's father's premises, Gun

Lane, Strood, on Wednesday evening last, and found the wheels, springs,

and axle tree produce, fresh painted. On the prisoner being called,

witness asked him where he had got them from, and he said he bought of

Mr. Young, a turner. Witness said he should take him to Mr. Young's, to

see if his statement was correct, and the prisoner then acknowledged

that he had taken the property from Mr. Tranah's.

The prisoner pleaded guilty.

Mr. Colyer, by whom the prisoner had been employed, said he never knew

anything dishonest against him before, but he was frequently troublesome

in regard to matters of work.

The Magistrate sentenced the prisoner to one calendar month's hard

labour at the house of correction at Maidstone, the Mayor expressing a

hope that this would be a caution to the boy for the future.

|

I am informed that the pub closed in 2009, following a rather chequered

history when it kept shutting and opening again. Following its final closure

it suffered one of those unexplained fires which nearly completely destroyed

the building.

LICENSEE LIST

FREEMAN Richard 1828-32+

TRANAH Arthur 1851+ (age 68 in 1851 ) )

TRANAH Mary 1858+

TRANAH Henry 1861-71+ (age 38 in 1871 ) )

GILES Harold 1955+

https://pubwiki.co.uk/BullsHead.shtml

http://www.closedpubs.co.uk/bullshead.html

From the Pigot's Directory 1828-29 From the Pigot's Directory 1828-29

From the Pigot's Directory 1832-33-34 From the Pigot's Directory 1832-33-34

Census Census

|