Page Updated:- Sunday, 07 March, 2021. |

|||||

Published in the South Kent Gazette, 23 May 1979. A PERAMBULATION OF THE TOWN, PORT AND FORTRESS. PART 8.

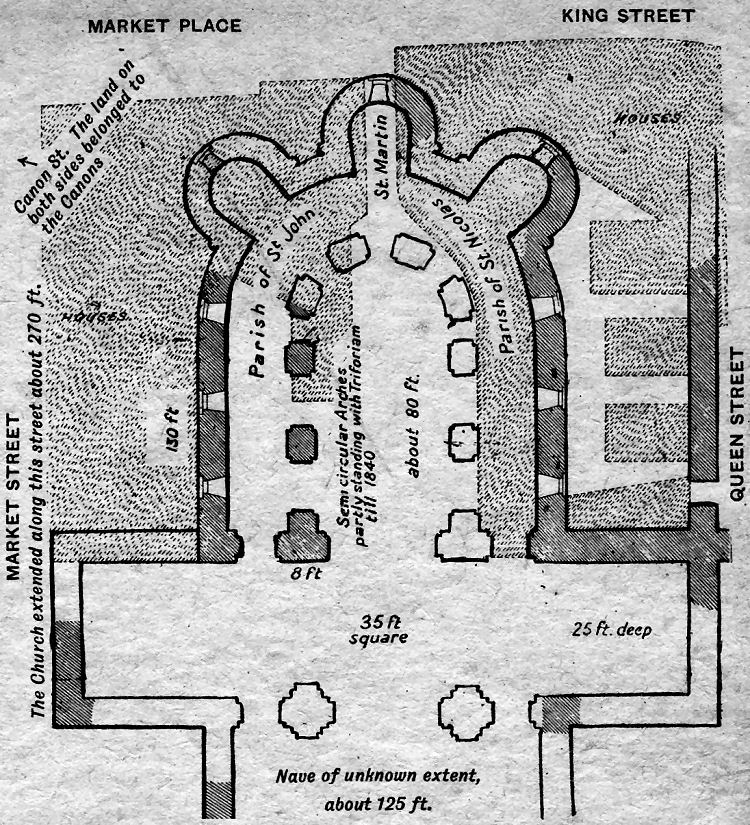

GROUND PLAN.

It will be seen from the ground plan that the church consisted of a nave of unknown extent, which occupied a considerable part of the open land at the rear, which, after the destruction of the church, was used as a burial ground for St. Mary’s parish; a transept, 25ft. in depth, over which there was doubtless a central tower; and, beyond this, extending about 80ft. towards the Market Place, was the apsidal choir, ending more or less flush with the present frontages. The choir had three projecting apsidal chapels, one in the centre, and the others respectively facing the north-east and south-east. As far as at present known, there is no written record of the work done by the Norman builders, but the remains of the choir, in the opinion of Dr. Plumptre, indicate that the portion of the church must have been rebuilt soon after the Conquest. Some say it was by Bishop Odo, the King’s brother, in 1070. The workmanship is that of the Early Norman period, and the style of the three apsidal chapels corresponds with several Early Norman churches both in England and in France. The walls were lined with Caen stone, a building material which came much into vogue immediately after the Conquest. Possibly, the nave of the church survived the fire of 1066, and the Saxon work, being old and inferior to that of the Normans, would account for that part of the fabric having totally disappeared. The ground plan only shows the design and arrangement of the transepts and the choir, and a very small portion of the north wall of the nave. The faint parts of the plan represent the portions of the foundations where there was not one stone left upon another, but the outline has been continued to complete the design. A curved wall of considerable height, usually called a tower, was the southern part of the central apsidal chapel of the choir, and the remains, showing the spring of the vaulting, indicate that is consisted of two stories. The narrow 4ft. space, showing white, through the middle of the central apsidal chapel into the interior of the ruins, was made — and specially mentioned in a deed — in the time of Queen Elizabeth, and was then used as a passage for the funerals to pass up when the land in the rear was used as a burial ground. A projecting mass of masonry of a similar shape to the piece of the central chapel used to be seen, covered with a sloping modern roof on the southern side, as shown in one of the old prints, (and of which there exist one or two photographs dating from about 1870 or earlier, photographs of the ruins as early as the 1850s being known), and a similar fragment stood above the houses on the north side. These were parts of the north-east and south-east apsidal chapels. There used to be a small portion of the outer wall of the north transept seen from Market Street. Three of the interior arches of the north side of the choir were standing in 1840, with the triforium and a small part of the clerestory over it. A large portion of the piers of the arch which was supposed to have supported the central tower was also standing at that time. The piers were solid blocks of flint rubble, with Caen stone dressings, about eight feet wide by six feet deep. All the arches were semi-circular, relieved by only one order, which was carried down the sides of the piers. The remains of this ancient church were particularly interesting as being a rare example of the three projecting chapels at the east end of the choir being left unaltered.

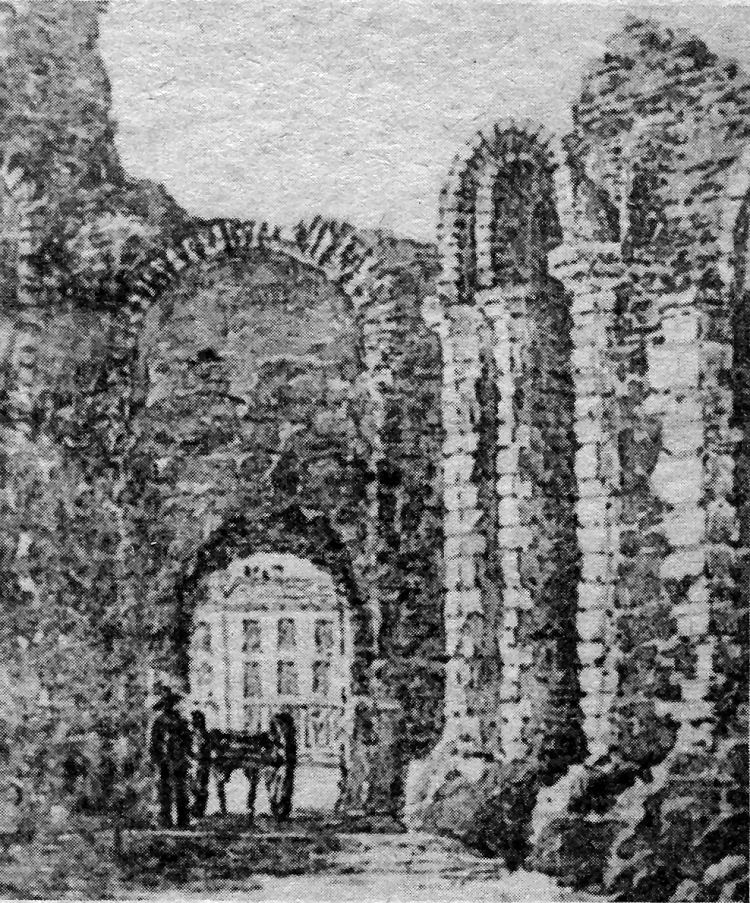

Another view of the ruins looking eastwards into the Market Square. This is the north aisle of the choir before the demolition of 1881. The spanned arch showed that the builders made use of much of the stone from the Roman baths on the foundations of which the church was built.

THREE CHURCHES IN ONE. Canon Scott Robertson, in a paper read in 1892 at the meeting of the Kent Archaeological Association at Dover, took the view that for two centuries prior to the Reformation the three parishes of St. Martin, St. Nicholas and St. John the Baptist had their churches under one roof here, the central chapel containing the altar of St. Martin’s, the southern that of St. Nicholas, and the northern one that of St. John. Many references in old documents, however, indicate that, earlier, the two latter churches did exist as separate fabrics. Those documents also record that there were three other chapels with an altar of Our Lady of Undercroft, in a crypt, under the east end of the church. When the Monastery was removed to Dover Priory, in 1159, St. Martin-le-Grand lost its ancient privileges as a Royal chapel, but became the mother parish church of Dover until desecration soon after 1528. During the parochial period the church was partially restored. No clear record is left as to how the quick destruction of St. Martin-le-Grand was brought about immediately after the Reformation, and how its extensive precincts, presumably including the whole area bounded by King Street, Queen Street, Princes Street, Market Street, and the Market Square, passed into private hands.

ST. MARTIN’S CHURCHYARD. Thomas Dawkes, yeoman and Common Clerk, had the lands known as the churchyard of St. Martin in his possession in the reign of Queen Mary, but the Corporation, who seem to have subsequently resumed possession, in the first year of Queen Elizabeth, let that property, by a deed long in their possession, to Antony Burton and his assignees. The orthography of the deed is curious. It states that St. Martin’s churchyard was let “from the ffeste of Seint Mixhell Th’archaungell next commynge after the date herof unto th’end and term of xxj. yeres then nexte ensuyng, fully to be completyd and endyd yeldyng and therefore yerely payeng unto the seide Mayer and Chamberlaines and to their successors for the tyme beyng, iiijsh. iiijd., of goode and lawfull money of Ingland ate ij. pryncipall ffeste in the yere, that ys to saye, at the ffestes of the Annunciacion of oure Lady Seint Mare the Virgyn and Seint Myxhell Th'archaun-gell, by evyn porcions to be payed and all repparacions about at the seide churche yerde, if any be, shall yerely be borne at the only propre cost and charges of the seide Antony Burton.“ The deed, after other formalities, concludes with reference to the narrow passage, before alluded to, thus:—“Provydyd alwys that the seide Antony Burton and his assignes do leve a lawfull waie for to bery the poore from tyme to tyme as ofte as nede shall requyre.“

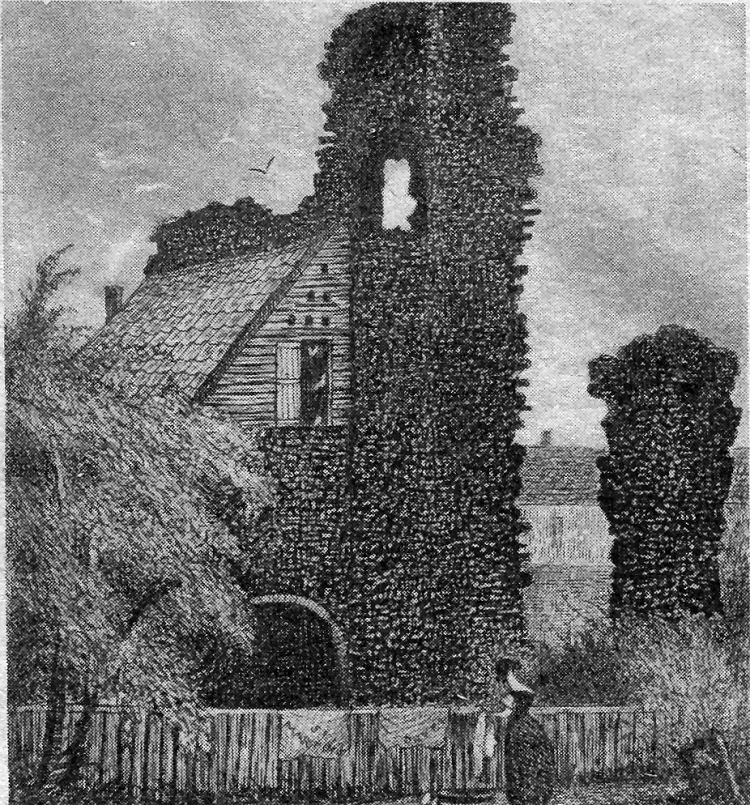

This quaint old print of a section of the ruins of the church of St. Martin-Ie-Grand, on a fence around which a woman is hanging her washing, is thought to depict a remnant of one of the side chapels.

|

|||||

|

If anyone should have any a better picture than any on this page, or think I should add one they have, please email me at the following address:-

|

|||||

| LAST PAGE |

|

MENU PAGE |

|

NEXT PAGE | |