Page Updated:- Sunday, 07 March, 2021. |

|||||

Published in the South Kent Gazette, 6 June, 1979. A PERAMBULATION OF THE TOWN, PORT AND FORTRESS. PART 10.

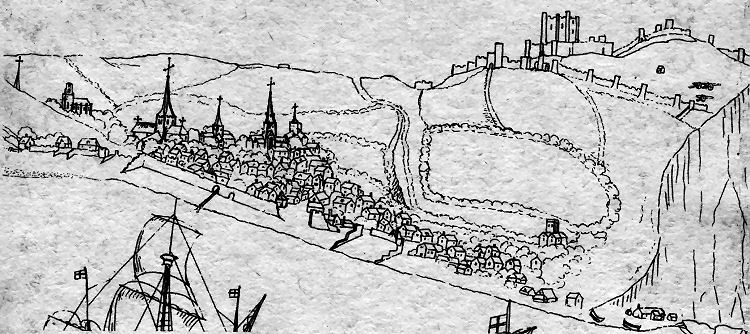

THIS small section of a drawing of Dover dated 1543— preserved in the Cottonian manuscripts in the British Museum—is particularly interesting because it tells us approximately where six of our early churches, in addition to the Maison Dieu, were located. Beginning on the right there is old St. James’ Church under the castle. Next is thought to be St. Peter’s, then the taller St. Nicholas’, a small St. Mary’s Church, then the imposing St. Martin-le-Grand, the Maison Dieu and the spire just visible on the left must be that of St. John’s but in the wrong place. It should be between St. Mary’s and the Maison Dieu!

NAILED BY HIS EAR. This scene was enacted under the walls of St. Martin’s in the Market Place, on the 28th of October 1533 (sic), just twenty days before Queen Mary ended her life sic (25 June 1533); so that widow who committed the sin of roasting mutton on a fast day, even if the Ecclesiastical Authorities, to whose mercy she was left, took no further orders, her incarceration must have come to an end when twenty days after “the cause was altered “ at Queen Elizabeth’s accession. (7 September 1533). Yet they were very barbarous in the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth. Here is a case of the use of the pillory in the Market Place two days after Elizabeth’s reign began. A man named Richard Shoveler, convicted by the Mayor and Jurats of being a common cutpurse, was sentenced as follows.—“That he shall goe to the pyllary, and ther the Bayllyes officer, or his Deputy, shall nayll one of his eares to the pyllary, and geve him a knyffe in his hand and he him leafe to cut off or els stande styll ther—thus to be done in the open faice of markett with a paper on his head.“ These two Market Place scenes will probably be considered sufficient examples.

MARKET PLACE ENCROACHMENT. In the year 1727 the house then occupying the site of the old Carlton Club was sold to one James Hammond, who demolished the stocks, cage, whipping post, and pillory then standing in front of it. The house being then old, he so rebuilt it that 10 feet of the frontage encroached five feet two inches deep on “the soil an inheritance of the Corporation.“ This led to an action at law at the Kent Assizes, in Michaelmas, 1735, and which was continued in the following year, resulting nominally in a verdict for the Corporation, but it was a drawn battle. The defendant, was ordered to re-erect the whipping post, pillory, and stocks (which are depicted in one old print to be reproduced in this book), which he did, making them movable, and paid the damages and costs; but, on the other hand, the Corporation had to grant to James Hammond a lease of the land encroached on for 900 years at a ground rent of 5/- a year. The house, therefore, was not set back, and, we fear, the Corporation accounts do not show any return of the modest ground rent. In spite of this ancient lease, and other leases on adjoining property, the whole of the frontage has long been freehold.

NORTH SIDE ANTIQUITIES. The north side of the Market Place is not without its ancient history. If we could view that spot as it was at the day-break of Dover’s history, what should we see? First, we come upon the Romans with their baths, at the western angle of the square, extending along the eastern end of Cannon Street. From the baths we see a fringe of shore or quay alongside the tidal water which bounds the square at the north-east corner. The wand of Time is waved, and, presto! the scene is changed. In place of the Romans appear the Saxons, who made little use of the Market Place, first turning their attention more to fortifying the Castle with mounds and towers. Godless heathen in the beginning, another stroke of the wand of Time brings them under the influence of Christianity, and they built churches. Their great work is the erection of St. Martin-le-Grand. Some of those Saxon builders needed graves before that great work was finished.

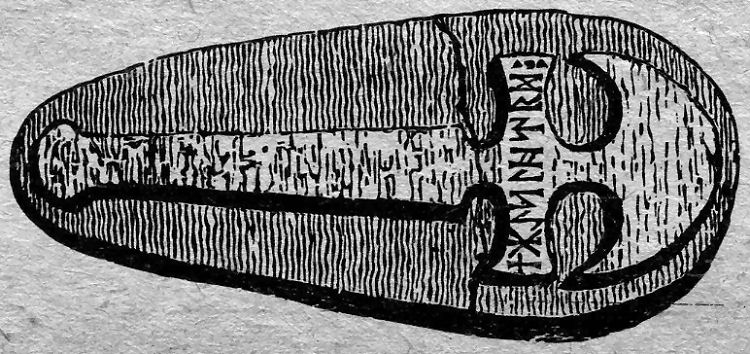

A RUNIC MONUMENT. There was evidently a place of burial in the Market Place before St. Martin’s was built, for the first real tangible piece of ancient history which carries us furthest back into the Saxon period is a monumental slab, bearing a cross and a chiselled memorial in Runic characters. The slab, shown below, is 6ft. long and 2ft. 3in. wide, and was placed in the Dover Museum, having been presented by the late Sir Thomas Mantell, who secured possession thereof. It was found in the year 1810, when excavations were being made for a cellar at the old "Antwerp Hotel" which stood on the Cannon Street corner. At the same time the foundations of the church of St. Peter, which formerly stood on that spot, were disclosed. The base of a pillar was found to be resting on two large fragments of stone, one on the other, and when they were removed it was found that the two pieces corresponded, and when placed together formed an entire monumental slab, having a cross on it, and a Runic inscription on the cross. The fact of this memorial stone having been found broken in two pieces, and placed merely as two pieces of building stone under a pillar of St. Peter’s Church proved that the memorial existed before the church.

The early Saxon monumental slab found in 1810. Broken in two it had been used as the foundation for a pillar of St. Peter’s Church.

How long before, it would be difficult to tell. The cross indicates it to be a Christian memorial, and probably it was in memory of a chief of the Jutes, an ally of the Saxons, that tribe having come into Kent in the year 428, and were one of the northern races that habitually used Runic characters in their records. The discovery of this relic under the "Antwerp Hotel" in 1810 aroused a good deal of interest, and it coming into possession of Sir Thomas Mantell, Mayor of Dover, Lady Mantell made a drawing of it, which was published by the Society of Antiquaries, from which Mr. Kemble read the name upon it, “ Gislheard.“ Later, another drawing was made, when it was found that in Lady Mantell’s sketch there was an error, and, this being corrected, the inscription was read by the Rev. D. H. Haigh, author of “Runic Monuments in Kent,“ as “Gisilheard.“ There were a good many other guesses and readings of those Runic characters by local antiquaries. Some read it “Gishotus,“ and others interpreted it “Angle Leoh Tred.“ There is no doubt but that the word “Gisilheard“ is the correct reading, but it conveys no meaning, the only points of importance being the characters in which the name is sculptured and the position in which the slab was found. They, combined, prove it to belong to the Early Saxon times.

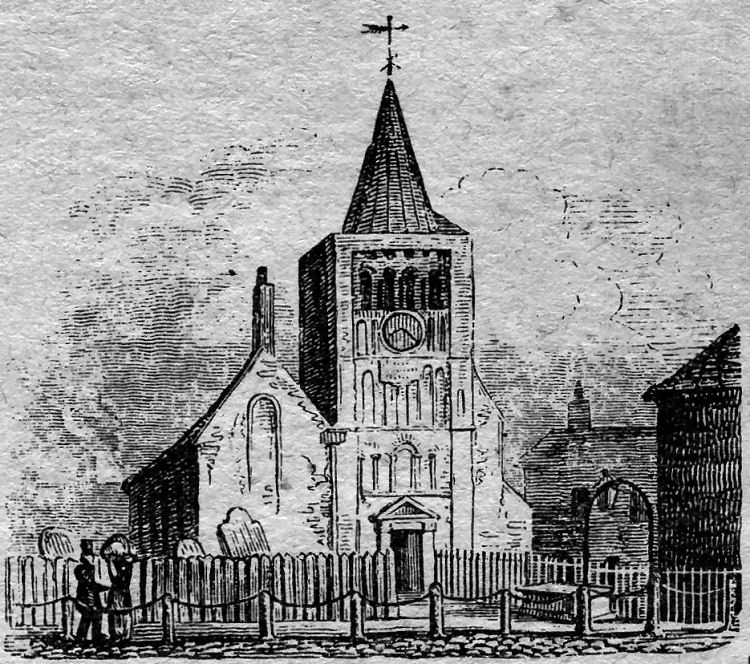

ST. MARY’S CHURCH, from an old print. The principal church in Dover for over 450 years it was once a minor religious house being completely over-shadowed by other churches standing practically alongside it—St. Martin-le-Grand and St. Peter’s, both in the Market Square.

|

|||||

|

If anyone should have any a better picture than any on this page, or think I should add one they have, please email me at the following address:-

|

|||||

| LAST PAGE |

|

MENU PAGE |

|

NEXT PAGE | |