Page Updated:- Sunday, 07 March, 2021. |

|||||

Published in the Dover Express, 28 March, 1980. A PERAMBULATION OF THE TOWN, PORT AND FORTRESS. PART 71.

WESTERN BEACH INCIDENTS Many incidents relating to this western beach may be culled from the annals of Dover, At Archcliffe Rock, in an open boat, during the reign of James II„ landed Isaac Minet, with his family and friends, who had been driven from Calais by a religious persecution. Inauspicious as was that arrival, the Minet family, together with the Fectors, exercised a great influence on the commerce and social life of Dover for more than two centuries. On this beach, also, when wars and rumours of wars threatened Britain in the latter part of the 18th Century, the Dover shipbuilders, commissioned by the Admiralty, built some of those ‘wooden walls“ in which Nelson and his co-heroes upheld the claim of Britannia to rule the waves. This western beach, since 1927, has been provided with a promenade, constructed by the Southern Railway on the breast of a sea wall that they built in order to reclaim a considerable portion of the foreshore, including the area known as the Western Block Yard, which during the construction of the Admiralty Harbour, was filled with the huge 40-ton concrete blocks utilised in that work. This block-yard occupied the top of the beach in front of the old Town Station, and access to the beach beyond was by a path between the block-yard and the station. Both path and most of the block-yard are now part of the railway, and there is, instead, a wide promenade of concrete facing the sea. This continues to the end of the station premises, where it slopes off to the beach. The sea wall has been continued by the railway as far as Shakespeare Cliff, the chalk got away when Archcliffe Tunnel was cut down being made use of to fill in underneath the old wooden viaduct which formerly carried the railway over the beach between the station and Shakespeare Cliff tunnel. This filling in of the space under the railway viaduct cut off the approach of the public to the cliff, on which is the Ropewalk Meadow housing estate. To replace this ancient right of way, the Railway Company, in 1928, built a ferro-concrete bridge to provide a connection between the beach and the cliff path there, known as ‘Peter Becker's Steos" or “Wellard’s Way,“

SHAKESPEARE CLIFF At the western extremity of this beach is the far-famed Shakespeare Cliff, which rises, in a striking manner, 350 ft. above sea level. The well known lines relating to it, in the play of “King Lear,“ are too familiar to need repeating here. The cliff is now pierced by the two main tunnels of the Southern Railway, cut in the form of Gothic arches, the two tunnels being divided by a partition of solid chalk 10 ft. thick. While this tunnel was in the course of construction, the Duke of Wellington visited it, on the 1st November, 1843, and walked through the whole length of it, three-quarters of a mile. At the foot of the steps descending the western side of the cliff to the shore (known as “Aker’s Steps“), the main shaft for the Channel Tunnel was commenced about the year 1880, and sunk to a depth of 164 ft., from the bottom of which a trial drift was driven about a mile and a quarter under the sea, after which it was suspended, in 1882, by order of the Government.

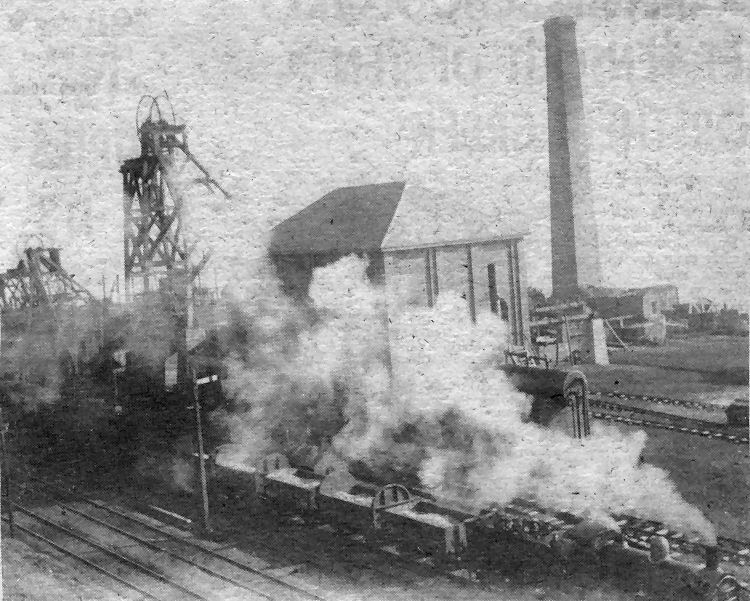

The ill-fated Dover colliery, on the Folkestone side of Shakespeare Cliff, which marked the birth of the Kent Coalfield. An exploratory borehall reached coal at 1,100 feet in February 1890, proving a theory of geologists that there was probably an extension of the French coal bearing strata under Kent. By the end of 1933 when four collieries were in production — output had reached two million tons a year, providing employment for 7,000 men. It was Sir Edward Watkin, Chairman of the South Eastern Railway Company and also associated with the unsuccessful Channel Tunnel Company, who called for the borehole to be sunk on the Tunnel site. The 2,274ft deep borehole went through 14 seams of coal varying from six inches to four feet thick, but no practical use was made of the discovery until 1896 when the Brady Shaft was sunk 280ft west of the trial borehole. A second shaft nearer the borehole, followed and later a third. But considerable trouble was experienced as water poured into the workings. At 450ft down over 54.000 gallons of water an hour gushed into the pit. In one accident, in 1897, eight of the sinkers were drowned. No coal was raised in any quantity until 1914 by which time the pit had changed hands several times. Bad conditions and the onset of the First World War finally resulted in the venture being abandoned.

The Channel Tunnel workings at Shakespeare, about 1880, which led to the discovery of Kent’s valuable coal seams.

|

|||||

|

If anyone should have any a better picture than any on this page, or think I should add one they have, please email me at the following address:-

|

|||||

| LAST PAGE |

|

MENU PAGE |

|

NEXT PAGE | |