Page Updated:- Sunday, 07 March, 2021. |

|||||

Published in the Dover Express, 27 March, 1981. A PERAMBULATION OF THE TOWN, PORT AND FORTRESS. PART 168.

FIRST CHAIRMAN The first chairman of the Dover Board of Guardians was the Rev A. B. Mersham; first clerk Mr William Cross; first master and matron Mr and Mrs Bentley. A vagrant directed to go to the workhouse for food and shelter would have been asked his name, age, birthplace, where he had come from and where the intended to go. He was then given a bath and food or drink and was expected to do a day’s work gardening, chopping wood or breaking up stones, reminiscent of the work of a prisoner in jail. After a day at the workhouse a tramp was sent on his way with a hunk of bread and cheese and a “way ticket“ which he could use to obtain a drink at a point half-way towards the next workhouse. If they had no set destination some men, if able-bodied, were permitted to stay provided they worked. They were often men out of work who travelled around looking for any job they could find, sometimes accompanied by their wives and even children, who were accommodated in a separate part of the workhouse. The children, if old enough, would be sent to the workhouse school while their mothers would be given cleaning, mending or washing to do. The elderly would be accepted for permanent residence, and the sick nursed in the infirmary.

COMING OF THE RAILWAY The construction of the railway embankment across Buckland Bottom, in 1850, with the two bridges over St Radigund’s and Union Roads, greatly altered the appearance of the valley; and the narrowness of the roads under those two bridges indicate the small amount of traffic that it was thought necessary to provide for at that period.

GASWORKS As soon as the railway was made, the Dover Gas Consumers’ Company selected the spot on the west side of the line, and applied to the Dover Corporation for permission to erect gasworks there, and also to open the streets to lay gas metres. Notwithstanding the fact that this company had no statutory powers, the Corporation favourably entertained the application because it suited their purpose to use the new company, and their projected works, as a means of bringing pressure to bear on the existing Gas Company, who, in the Session of 1860, had a Bill in Parliament for increasing their capital and extending their powers. Ultimately the Corporation made an agreement with the existing Gas Company, and the consumers’ project came to nothing; but four years later, the Dover Gas Company finding that their works in Trevanion Street were too cramped to meet the demands of the town, obtained an Act of Parliament, enabling them to raise further capital, and to build new gasworks in Buckland Bottom. These powers were obtained in 1864, under an undertaking given to the Corporation that the manufacture of gas in Trevanion Street should be abandoned within seven years from that date. In less time than that, the manufacture of gas was altogether transferred to the works in Union Road, which were built on a sufficiently large scale to meet all the requirements of the town at that period; but during the following 100 years Dover expanded quickly and the use of gas for lighting, heating, power and cooking increased even more rapidly than the population, with the result that these Coombe Valley works were added to again and again. In the 1960s there were repeated complaints about pollution of the atmosphere by the massive gas undertaking, which by that time was supplying the gas supply needs of a large part of Kent. There were complaints too about dust from the huge stockpiles of coal kept on the hillside, despite the installation of a sprinkler system. Then came the discovery of natural gas under the North Sea and the gasworks rapidly became redundant and the majority of buildings and plant were demolished. With the plant disappeared also a local source of fuel— coke, which was a highly valued by-product of gas-making.

INSIDE THE WORKS It was fascinating to look inside these works, and watch the process of gas-making, following the fluid, through its various stages, from the coal stores until it appeared as the finished article in that triumph of ingenuity, the incandescent gas lamp or the gas cooker or sittingroom fire. In the early days there were great vaulty coal depots, capable of storing 4,000 tons of coal, in which heat, light and power, as well sis several valuable residual products used in art and science lay latent. The subsequent stages of manufacture involved the fierce fires of the retort houses, where, by the agency of fervent heat, the volatile gas was crudely separated from the coal, and refined stage by stage, leaving the coke, the tar, and the ammonical fluid behind, to find their varied uses in the stove, the furnace, the dyehouse, the laboratory and in the tarred paving of the streets; while the gas itself was stored for use in the numerous gasholders, which were never weary in sending forth, through the network of pipes, which spread through the town like the veins of the human body, the gas which cheered with light and warmth thousands of Dover homes. Some gasholders remain in East Kent for storage purposes.

GAS WORKERS The gasmaking plant, long under the watchful eye of Mr Willsher Mannering, the Chairman of the company, was not only a thriving manufactory, but as a place of breadwinning was an important industrial centre, from which were drawn the weekly wages which kept many of the Buckland homes together. The building of the gasworks was the immediate cause of a rapid growth of the population in Buckland Bottom; and yet there was those who urged that those works would prevent the land from being used for building. When it was proposed, in 1860, to erect the projected works of the Consumers’ Gas Company there, Mr William Cross, the clerk to the Dover Union, by direction of the Board of Guardians, wrote a strong protest to the town council against such works being erected in the neighbourhood of the workhouse, as it was alleged that it would deteriorate the value of their land and buildings, and be prejudicial to the health of the inmates of the house, and more especially to the forty inmates then in the infirmary; nevertheless, within four years from the building of the gasworks, fifty new houses had sprung up in its immediate vicinity, to be followed by many more before the works became redundant, such was the demand for building land in the valleys.

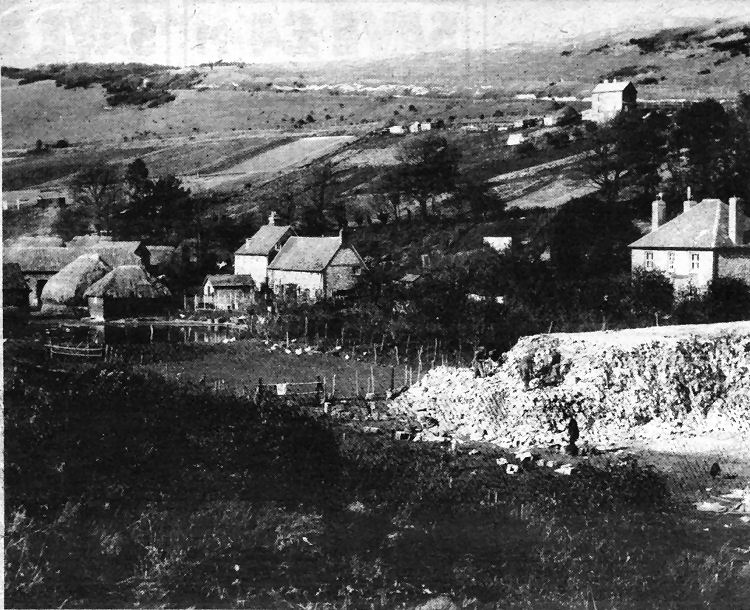

The town’s refuse creeps forward and threatens to engulf the farmhouses and thatched barns clustered around the pond of old Coombe Farm, In 1938. Dover Corporation bought the farm, which for centuries had been almost completely isolated at the end of Coombe Valley, to enlarge the area for controlled tipping of refuse. The workmen on the right appear to be sifting through the rubbish although their official role was to cover it up with top soil and chalk. The farm completely disappeared sometime after the war and the area was subsequently developed as the town’s new industrial estate. Beyond the farm, on the rising ground below the road to St Radigund’s Abbey, new Corporation allotments were provided to replace those displaced by housing development in the valley. The farm stood near the junction of the track to Poulton Farm, higher up the valley, and the road to St Radigund’s.

|

|||||

|

If anyone should have any a better picture than any on this page, or think I should add one they have, please email me at the following address:-

|

|||||

| LAST PAGE |

|

MENU PAGE |

|

NEXT PAGE | |