Page Updated:- Sunday, 07 March, 2021. |

|||||

Published in the Dover Express, 6 June, 1980. A PERAMBULATION OF THE TOWN, PORT AND FORTRESS. PART 85.

A later royal charter was granted in 1381, confirming the passage monopoly, Channel traffic being decoyed to other ports, mentioning that. “ the inhabitants of the town have almost entirely left it, and half the town is empty and desolate, and its houses have, in many cases, fallen into ruins, will very likely be destroyed, and the inhabitants compelled to leave it, it is said, unless some fitting remedy be provided quickly." This charter, in addition to re-affirming the early monopoly-' gave the townspeople power to make such penal ordinances as would tend to encourage the building of ships for the Passage, and to concentrate the Channel traffic at Dover. This royal ordinance was useless, because no one enforced it. Hythe and Sandwich poached on the cross-Channel traffic, thereby diverting the revenue, by which the shipping and the harbour should have been maintained. In the year 1435, the town of Dover sent up another piteous petition, for the enforcement of the monopoly, urging that the “town is set in the uttermost part of your realm, next unto your enemies, and hath no means of comfort or release, but only by the means of the said Passage." After a delay of two years, in 1467, the monopoly was confirmed by the authority of Parliament, and a penalty of five marcs provided against offenders. That was in the time of the Wars of the Roses, when the tenure of power was uncertain, and there was no reliable authority to enforce the Dover Passage monopoly. During that unsettled period, Dover Harbour was utterly neglected, and its traffic diminished almost to vanishing point.

EASTERN HARBOUR LOST The tides, in their courses, fought against Dover. The continuance of the eastward drift of the shingle so choked up the little landing place, that the owners of passenger vessels had a legitimate excuse for using some other port. The lucrative business of the Passage was lost, and the mariners of Dover were driven to seek a precarious existence by “faring," a calling which, at that time, seems to have been akin to that of a sea robber. Then it was that the. Eastern Harbour was entirely abandoned, and John Clark,1 the Master of the Maison Dieu, prevailed upon Henry VII to grant aid. for providing shelter for boats on the western side of the Bay. But, although the Eastern harbour was abandoned a section of the Dover boatmen continued to operate from the open shore at East Cliff, a practice which continued until recent years. Now7, due to harbour development and ;the scouring action of the sea, there is hardly any beach left there at high tide on which to keep boats.

PROJECTS TO RE-OPEN HARBOUR Many years after the Eastern Harbour was abandoned, there were projects for retrieving it. In the reign of Queen Mary, there was a plan drawn for carrying the haven through the town; and, in 1784, Sir Thomas Hyde Page, an eminent engineer, then engaged at Dover, wrote: “Considerations on the state of Dover Harbour, and its relative consequence to the Navy of Great Britain," in which he contended “that the present situation of Dover Harbour is contrary to nature, and incapable of answering any good effect, until it is restored to its original ancient situation to the eastward." His ambition was to give the Royal Navy “a permanent and useful sea port at Dover." probably, the great Admiralty Harbour, which extends east and west, would have satisfied Sir Thomas Hyde Page's aspirations.

THE WESTERN HARBOUR Dover Harbour began to grow, at Archcliffe Point, in the days of Henry VII, when necessity compelled the mariners to migrate to the western horn of the Bay, where the Master of the Maison Dieu helped them to form that little harbour, which they called "Paradise.“ That harbour, in the course of a century, was utterly choked up, and another harbour was gradually developed in front of it. The lavish expenditure of Henry VIII established the Dover inner harbour. The King first provided means to mend the breaches in the original Paradise Harbour, and to construct some western groynes, to keep back the shingle. Later, he entered upon works on a large scale, parts of which were completed, extending from Clarence Place towards the South Pier. Beyond the works that were completed, a space was left, probably intended for a western entrance, outside which the King commenced building a great stone breakwater, or mole, 300 yards in length. He laid the foundations, consisting of great blocks of chalk, which were hewn on the western shore, and carried by a vessel, with nine keels, and sunk in the position desired. After bringing up this breakwater three fathoms, and spending £50,000, Henry VIII left the mole incomplete. The work survived into the 20th century being visible just outside the old harbour mouth, at low water. It was known as the Mole Rock, and was formerly called the King’s Foundation.

ELIZABETHAN HARBOUR ENQUIRY Henry VIII left no funds to complete or to maintain his harbour works. During the six years of the reign of Edward VI, nothing was done; nor yet while Queen Mary was on the throne, with the exception of showing great interest in Dover haven, and making some promises as to its repair, was anything accomplished. It was not till about 23 years after Elizabeth ascended the throne, that the restoration of Dover Harbour was earnestly commenced. Action was preceded by an enquiry held by the Lord High Admiral. The mariners of Dover, on that occasion, testified as to the decayed condition of the haven. One of them deposed: "The great rocks that were sunk by Henry VIII do still lie there, and are not removed by the violence of the sea, but by wearing of them, or the looseness of the ground under them, have sunk somewhat lower and lower." Other evidence taken showed that the harbour left by Henry VIII, had been so choked, that there was no entrance save by a very narrow and useless channel. This enquiry, further, placed on record the fact that, at that time, a shelf of beach and ooze had been formed across the Bay, retaining the water behind it, so that there was a long standing pool, that was 12ft. higher than the sea at low water. This long standing pool of water was regarded as an important factor in the Elizabethan development of Dover Harbour.

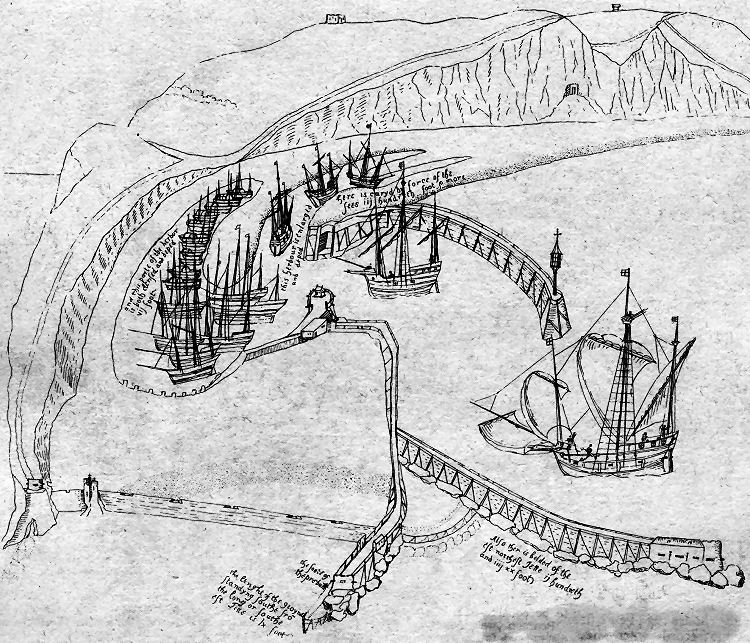

Another piece of Dover’s history. A drawing of the Western Docks area dated 1543, It is part of a larger engraving preserved in the Cottonian manuscripts in the British Museum. Another section of it, showing the site of seven of Dover’s early churches, was reproduced in Part Ten of this reprint of John Bavington Jones’ Perambulation of the town, port and fortress of Dover, published in 1907.

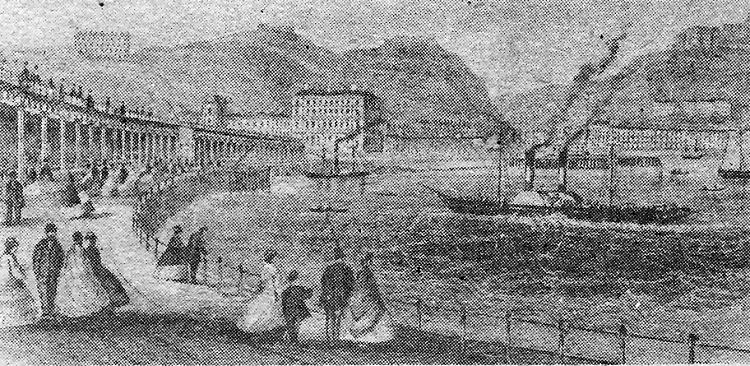

By way of a contrast is a 19th century view of the Admiralty Pier and the harbour.

|

|||||

|

If anyone should have any a better picture than any on this page, or think I should add one they have, please email me at the following address:-

|

|||||

| LAST PAGE |

|

MENU PAGE |

|

NEXT PAGE | |