|

From the Kentish Gazette 5 June 1838.

(Full

account found from this link. Paul Skelton)

Full Particulars, up to the latest hour last night, of the conflict

between Sir William Courtenay and a detachment of the 45th Infantry,

in the Blean Woods, near Canterbury, on the 31st of May; and the

evidence adduced up to the same period, at the Inquests upon the

bodies.

It is now six years since the individual, whose death has entailed

misery and ruin upon the families of a large body of agricultural

labourers, first made his appearance in the county of Kent.

His assumption of the Devon Peerage, and his claims to other titles

and property, together with his reported wealth, the narratives of

his Palestine pilgrimages, his magnificent and costly Eastern mode

of dress, his manly and elegant figure, his impressive countenance,

and his dauntless spirit, induced people of every grade to look upon

him as a man of "more than common cast."

It would be needless to enter into a recapitulation of the eccentric

man’s life during the few month’s he sojourned in the city of

Canterbury. His contest for parliamentary honours in opposition to

the Hon. Rd. Watson and Lord Fordwich, proves that, however well

qualified for winning the golden opinions of the poorest and most

ignorant, art and study, or a close observance of human nature, had

endowed him with a tact which made him estimable in the eyes of the

better educated, and enabled him to ingratiate himself into the good

opinions of the learned by an originality of idea, a brilliancy of

conception, and a fluency of choice and classical language. These

distinguished acquirements carried public opinion in his favor even

among the most sceptical, and from his friendly disposition to the

poor, and general urbanity he dwelt in the hearts of all men, until

the wildness of his schemes to retrieve, as he said, his lost

property, and the exposure of the deceit and falsehood which he

practised, overwhelmed him suddenly with disgrace and infamy.

We subjoin a brief notice of his early connexion with Canterbury:—

Sir W. Courtenay first appeared in Canterbury in the Michaelmas of

the year 1832; and the first rumour was, that an eccentric character

was living at the "Rose Inn," who passed under the name of Count

Rothschild, but had been recently known in London by the name of

Thompson. His countenance and costume denoted foreign extraction,

while his language and conversation showed that he was well

acquainted with almost every part of the kingdom. He often decked

his person with a fine suit of Italian clothing, and sometimes with

the more gay and imposing costume of the eastern nations. In

December of the same year he surprised the citizens of Canterbury by

offering himself as a candidate for the representation of the city

in parliament, and created an entertaining contest for the honour

long after the sitting candidates had composed themselves to the

delightful vision of an unexpensive and unopposed return, he was

also a candidate for the eastern division of this county, but polled

only four votes, the county voters having derived a lesson of wisdom

from the sad effects of his former freaks and follies. After

striving in vain to possess himself of a seat in parliament, at

least a return of having been elected for one, the adventurer

appears to have studied with much more ardour and vigilance than

before to captivate the affections of the lower orders in the city.

He made it known that his condescension was as great as his rank and

wealth, and that he should be willing to accept of invitations to

visit the humblest families — to eat and drink at the peasant’s and

the laborer’s table — to make one of a larger or smaller party at

the lowest public-house, — to enrol his name in the meanest society,

and to have it published abroad that Sir William Courtenay preferred

being the companion of the cottager and the friend of the poor. It

is easy to conclude that such intelligence charmed a million hearts,

and obtained entreaties for his company from every quarter. So

numerous were his engagements, that he was obliged to run or ride

from house to house, taking a slight repast at each, and generally

concluding the day at a banquet prepared by a number of his new

friends in some club-room.

During the whole of this period, the excitement produced by Sir

William was beyond conception. He set at defiance the civic

authorities, and the Mayor and Magistrates of Canterbury, although

professing popular principles, were obliged on one occasion to seek

safety in military aid.

Shortly after this he got into a more serious difficulty, by

interfering in behalf of a party of smugglers who were captured and

conveyed to Rochester for examination. The outline of this affair is

as follows:—

In the month of February an action took place between her Majesty’s

sloop Lively, a revenue cruiser, and a smuggling boat called the

Admiral Hood, near the Goodwin Sands, which ended in the capture of

the latter, which, with the crew, was taken to Rochester for

adjudication. On boarding the smuggler no contraband goods were

found; but, during the chase, she was distinctly seen by the Lively

throwing tubs overboard, and some of them were marked and picked up

by the crew of the cruiser. On the examination of the smugglers

before the magistrates at Rochester, Sir William Courtenay made his

appearance, attired in a grotesque costume, and having a small

cimetar suspended from his neck by a massive gold chain. On one of

the men being examined. Sir William became his advocate; but the man

being convicted, a professional gentleman from London defended the

next, and Sir William presented himself as a witness, and swore that

he saw the whole transaction between the Lively and the Admiral

Hood, and was positive that the tubs, stated to have come from the

Admiral Hood, had been floating about in the sea all the morning,

and were not thrown overboard from that vessel. The object of this

statement was evidently to prove that the Admiral Hood was not a

smuggler, and consequently to procure the liberation of the men. The

solicitors for the Customs, having undoubted evidence that this

testimony was false, determined to proceed against an individual who

had been guilty of such a public and daring act of perjury. The

trial came on at Maidstone, before Mr. Justice James Parke, on the

25th of July, 1833, when he was found guilty of wilful and corrupt

perjury, and sentenced to imprisonment in gaol for three calendar

months, and at the expiration of that term to be transported to such

place beyond the seas as his Majesty, by and with the advice of his

Privy Council, should direct, for the term of seven years. Before,

however, the three months’ imprisonment had expired, it was found

that Sir William was completely out of his senses; the sentence was

annulled, and he was sent to the Kent Lunatic Asylum at Barming,

where be has been confined until a few months since.

Whilst at Barming-heath his admirers, particularly among the poorer

Classes, seized with avidity all tidings of him. They supplied him

regularly with every necessary and luxury, and contributions were

made weekly for his maintenance in a style befitting his exalted

situation in life. A few months only were suffered to elapse ere

addresses, memorials, and petitions, praying for his le-lease, were

forwarded to the Government. After a detention of four years, Mr.

Toms, of Cornwall, the father, and Mrs. Toms, the wife of the

self-dubbed Knight of Malta, applied for his release, and on the

father offering to be responsible for his conduct, and to be bound

to take care of him. Lord John Russell directed the case to be

inquired into, and reported to him. The surgeon represented that,

although of unsound mind. Sir William was not a dangerous madman,

and the Home Secretary signed his order of discharge from

confinement. With old Mr. Toms' acquiescence, his son paid a visit

to Mr. Francis, of Fairbrook, near Canterbury. The Knight domiciled

with the family, and they lived very comfortably for several months.

Sir William amusing himself by traversing and exploring the immense

woods which intersect — nay, almost cover — that part of the

country. At length a rupture broke out between the friends, on the

subject of his parentage and prospects; and he was, ultimately,

ordered to quit the house. This he did, and his clothes and property

were conveyed to another destination, and then removed to Bosenden,

the residence of John Culver, where Sir William took up his abode.

He now paid frequent visits to the husbandmen of the neighbourhood.

It may be scarcely credited, but the influence which he obtained

over the agricultural laborers was not merely the result of his

complacency.

He interlarded his conversation with stories of his Divine agency —

affirmed himself to be the Redeemer, and that the eternal happiness

and misery of mankind was at his direction. In conversing upon these

topics he threw into his manner so much earnestness and wildness,

that the ignorant audience, if they felt any doubt of his superhuman

power, did not venture to express it. Whether at this time he

entertained the projects which his partisans have declared he

subsequently conceived is a matter of doubt — and it is much to be

questioned whether he would have gone farther than proclaimed

himself a Supreme Being, and have exacted implicit obedience from

his misguided friends, had not some of the more respectable

inhabitants of Boughton and the adjacent parishes, and also of

Canterbury, become objects of his wrath from the persecutions and

degradation he fancied he had received at their hands.

One of his hands had been lacerated years back by some accident, and

he Converted the circumstance into a corroborative proof of his

story. Me pointed out the scared wounds, and solemnly affirmed that

they were the marks of the nails which pierced him when he suffered

for their sins on the Cross. Another wound in his side he exhibited

at times, as proceeding from the spear with which the Roman soldier

thrust him. He pronounced himself invulnerable — neither sword nor

gun-shot could injure him, and that he was two thousand years of

age. That he could render all who believed and obeyed equally

impervious to outward assault; and that if he permitted himself to

be slain at any time it would only be to show that he could of

himself rise again. Nor was this all; — one evening, when he was in

the midst of his followers, and had been lecturing them upon

spiritual subjects, he went to the door, and calling their attention

to his movements, pointed out the north star. To convince the

unbelieving, who had as yet seen none of his works, he said he would

shoot the star with his pistol, and it should drop into the distant

ocean, he accordingly fired, and his fanaticised audience stood in

mute astonishment, and on recovering their breath, exclaimed they

had seen it fall!

We could multiply these instances, but they are heartrending and

sickening to the well-informed mind. We shall relate but one more,

and this we shall do, because up to Saturday night his followers

obstinately persisted in its belief. To introduce the incident here

is somewhat out of the order of events, but as connected with the

subject of our present paragraph, we append it. Previous to the

conflict with the soldiers, Sir William stated to the persons who

assembled round him at Bosenden farm, that if he fell in the

engagement, some one must immediately pour water upon his lips. It

would be an act of special grace for any one to be suffered thus to

treat him, and would bring down heavenly blessings upon the favoured

individual. The application of water to his lips at this important

crisis, would preserve him from mortal death, and, he should rise up

again and live amongst them, even though his body had been cut to

pieces by his enemies. Sarah Culver, the daughter of the farmer at

Bosenden, actually walked a distance of half a mile with a pail of

water, which she poured on his lips and stanched his wounds with, as

he lay dead on the field of carnage. His surviving followers remain

firm in their expectation that as his behest was complied with, he

will rise again, and appear a Saviour and a King amongst them,

either on the third or seventh day.

Such was the enthusiastic and fanatic state, to which he had wrought

the minds of upwards of one hundred persons previous to the day of

his death.

We shall now trace his conduct from the Sunday which commenced the

week of his outrages. He had won to his interests many, not merely

labouring men, but small farmers — and persons doing well in the

world. It has been said that his partizans were men suffering from

the operations of the New Poor Law Act, and that their distresses

drove them to acts of rebellion. This is not true. We cannot on

inquiry find that a parish pauper was of this party. They were all

in full employ. Wills, who seconded Courtenay with so much

resolution at the fight, lived in a good house at Fairbrook, has

property of his own, and farms a small portion of land. Wraight, who

is killed, occupied sixty acres of land — eighteen of which were his

own property — had a team of horses, and was doing prosperously.

Foad was well off, and was much esteemed by his wealthy neighbours;

and several, or nearly all, were in the employ of excellent masters,

and had been so for a series of years.

On Sunday Courtenay visited Wills. In the afternoon he had tea at

Kennett's, a labourer’s, at Dunkirk, at the foot of Boughton-hill.

After tea he preached a sermon to a large party of his followers,

one half of whom were women. On Monday he was in the neighbourhood

of Boughton, and was met by small parties of labourers, with whom he

conversed earnestly and shook hands. A numerous party of people of

both sexes, visited him at Culver’s, at Bosenden, by invitation to

tea on Monday evening.

On Tuesday morning, early, Courtenay met a party of fourteen or

sixteen unarmed men, residents of Dunkirk, and proceeded at their

head through Boughton, calling at Mrs. Palmer’s, a strong partizan,

and other shops, and purchasing bread and cheese. They then marched

to Wills's, at Fairbrook, from which place he sent for a pound of

tobacco and beer for the men. Here the party regaled themselves for

two or three hours, and several flocked to his standard. When at

Boughton he was attired in a shooting jacket, but having mustered a

company of determined and powerful men, to the number of between

forty and fifty, he bedecked himself in the showy vestments with

which he had aforetime imposed upon and deluded the citizens of

Canterbury. His "gold"” chain and glittering orders were exposed,

and his pistols and dirk were stuck in his belt.

They then proceeded to Graveney, and at a bean stack a loaf was

broken asunder and placed on a pole. Thence they proceeded to

Goodnestone, near Faversham, producing throughout the whole

neighbourhood the greatest excitement, and adding to their numbers

by the harangues occasionally delivered by this ill-fated madman. At

this farm Courtenay proclaimed that he would "strike the bloody

blow," and introduced a bundle of matches into the stack, but which

fortunately did not ignite. It is uncertain whether he intended to

fire the stack at that moment, to infuse terror in the

neighbourhood, or whether his conduct was directed by a desire to

show to his party that he should not hesitate to have recourse to

the most outrageous acts to promote his views, and that he

considered himself superior to mortal vengeance or human

retribution. It is reported, that this and other stacks were to be

lighted as a signal to confederates who had not yet joined his

standard on the flag of defiance having been unfurled, and that all

who did not wish to be victims of his desolating power, or who

desired to aggrandize themselves by the ruin of others, must, at

once, declare in his favour. Certain it is, that mysterious threats

and imprecations were chalked on the walls and gates in the adjacent

country, foretelling the arrival of a day of devastation and

bloodshed, when the fire of the Lord should be kindled, and the

enemies of godliness and the oppressor should meet with the just

reward of the wicked. The Union workhouses were to be opened, and

the inmates released, and the wails razed to the ground. Many of the

active officers of justice were to be immolated — an instance of the

cruelty to be proclaimed was witnessed by the murderous and

barbarian like treatment received by the constable on the following

Thursday — and the lands and possessions of the despoiled were to be

distributed among his followers. Several of his active and zealous

attendants were already, by promise, rich and great men. To some he

had allotted farms — to others, treasures — and the rewards to all

were to be measured by the daring and firmness they evinced to his

cause. None appear to have questioned either his ability or right to

rob, and destroy, and murder. He had in repeated instances exhibited

his Divine origin, and it was not for them to dispute the behest of

a man with whom, by an unaccountable fascination, they had leagued.

They next proceeded to a farm at Herne-hill, where Courtenay

requested the inmates to feed his friends, which request was

immediately complied with. Their next visit was at Dargate-common,

where Sir Wm., taking off his shoes, said, "I now stand on my own

bottom." By Sir William’s request his party went to prayers, and

then proceeded to Bosenden-farm, where they supped, and slept that

night.

On Wednesday morning the party left Bossenden. They had slept all

night in a barn, where a guard had been kept over them to prevent

intrusion. At three the band left the barn, and passing through

Brighton, Ospringe, Greenstreet, Bapchild, went to Sittingbourne,

and breakfasted at the "Wheat Sheaf." By Courtenay's orders all the

men were armed with bludgeons; he himself being laden with pistols

and a dirk. A white flag, bordered with blue, and bearing the device

of a lion rampant, was borne in front of the procession. For the

breakfast Courtenay paid 25s.; and shortly afterwards his party

increased to nearly a hundred strong. From Sittingbourne they

marched to Newnham, again partook of refreshment at the "George."

Courtenay asking the labourers as they passed to join his ranks, — as

he would provide them with provisions and money From thence they

directed their course to Doddington and Eastling, over Throwley

Forstall and Seldwich Lees, through Lord Sondes’ park to Sellinge,

and rested in a chalk-pit belonging to Mr. Clackett, at Gushmer.

Having stayed here two or three hours they formed its rank at the

sound of a bugle, and proceeded back, passing at the foot of

Boughton Hill, returned to Culver's house, at Bossenden. This round

was a distance of about 30 miles readied Culver's at about five

o'clock. They had now about sixty in company, who had supper at

Culver's. A grey horse, on which Courtenay had figured at Canterbury

during his better days, was led in front of the party by Tyler. The

brute is a most vicious one, and none but Courtenay dared to mount

him.

In the evening, at about nine o'clock, Mr. Curling, of Herne-hill, a

respectable farmer, went from the "George Inn" at Boughton, to

Culver's house, to inquire after some of his men, who had left his

employ. On reaching Culver's house he was hailed by Sir William

walking in the garden. He demanded, in a very authoritative tone,

"What do you want?" Mr. Curling replied, "I'm looking after some men

who have run away from my service." He rejoined, "We have none of

them here and after a few more words Mr. C. left and returned to the

"George."

The magistrates having granted a warrant to Mr Curling to apprehend

his men, supposed to have joined Courtenay's party, he put it into

the hands of Mears, the constable, who on Thursday morning proceeded

to Culver's residence to execute it.

The circumstances attending to the death of the constable will be

found in the report of the inquest on the body. We shall, therefore,

make no further reference to the horrid and brutal murder here, but

proceed to detail the occurrences which subsequently transpired. On

the two assistants escaping, they applied to the magistrates for

aid, which was promptly rendered. Courtenay had an interview with

this force near the ozier bed and exchanged fires, and madly exposed

himself to three shots returned to his men, and exclaimed, "You see,

nothing can touch me I am proof against steel and bullet." The

magistrates offered a reward for his capture but no one ventured on

the dangerous undertaking. Expresses were sent to Canterbury for the

military; and after considerable delay, a reinforcement arrived.

Courtenay had now left the ozier bed; his party carrying oak boughs

over their shoulders, and proceeded to Mr. Francis's. Here he

demanded gin and water for his men, but on the suggestion of Mrs. F.

that beer was their more usual beverage, he desired they might be

supplied with it. He took gin and water himself. After a long lapse,

it was reported that the military were sent for and he drew off his

men towards the woods, and took his station in a thick jungle. This

position was admirably adapted for Guerilla warfare. They lay on the

side of a gentle slope, hid in underwood of four or five years’

growth. In their front the base of the hollow was comparatively

clear, only a few oak stems and low shrubs growing on it: whilst on

each flank and behind him the wood was almost impervious. About a

quarter of a mile in his rear was Culver's house. The men lad down

in the brushwood, and the only sign of their temporary habitation

was the occasional shaking of the boughs as they crept about to

communicate orders.

From whatever cause Sir William chose this spot, he could not have

selected one more easy of defence had he permitted his friends to

use fire-arms. It is said he had aforetime had the place pointed out

to him as where the Danes fought a sanguinary battle, and he

intended it to become celebrated for the defeat of a military force

by a body of unarmed peasantry. At two o’clock a division of the

45th marched into the dingle, accompanied by Dr Poore. N. Knatchbull,

esq. W. H. Baldock. esq. R. Halford esq. and other gentlemen. The

military formed a double line of fifty, extending across the bottom,

and on the Church wood side of a rivulet dividing it from Bosenden,

and within twenty or thirty yards from Courtenay’s band. Ten rounds

of cartridge were served to each man and they were ordered to load.

During this operation Sir William's party lay perfectly quiet, and

whilst the soldiers were waiting for "the word." Courtenay thrusting

his scimitar into the long grass, took up a bludgeon, and advanced

towards them. At the same moment Lieut. Bennett advanced from the

ranks, stepped over the rivulet, and in disobedience of the order of

his superior officer to "fall back," still approached to Courtenay.

It was at this moment he met his death. The tragic scene is related

in the examination at the inquest.

We visited the spot on Saturday. It is a sweet, secluded and

romantic glen — the hills mantled with luxuriant shrubs rising with

a gentle ascent on all sides, the approach is by two roads each of

which the military took. At the bottom of the glen the brushwood has

been cleared away, and the view until the eye rises to the elevated

ground is uninterrupted and picturesque — oak trees overtopping the

copse at short distances throughout the whole extent. The long grass

where Courtenay and his band were concealed is bent by the recumbent

posture they assumed. The scene of the conflict is still more

distinct. The grass as if in sympathy with those who so lately

encumbered it with their inanimate and ghastly forms is dead or

withering away. Pools of blood met the eye in various directions.

The twigs of the saplings and the smaller branches of the underwood

are split and riven by the bullets of the musquetry, and the stems

of the oak show by their multifarious incisions how sharp and close

was the firing. Where a few days ago the shouts of rebels and the

report of deadly musquetry were heard - now nought only reached our

ear but the gentle swelling of the zephyrs, and the melodious and

shrill warblines of the woodland songstresses.

The conflict lasted but a few minutes. The fall of Mr. Bennett was

the signal for a general assault by the military, and Courtenay fell

next by a ball which penetrated his left shoulder. He fired a second

pistol, but whether it took effect has not been yet ascertained. His

attack was resolutely supported by his followers, who abetted him

with a daring and determination worthy a better cause. On seeing

their leader fall they fought desperately, and, notwithstanding the

deadly weapons with which they were assailed, they rushed forward to

the muzzles of the guns, and attempted to beat them down or to wrest

them away. The steady fire of the soldiery however, was too

effective, and after seven of the party had been stretched dead on

the field, and a greater number wounded, they took to flight.

The soldiers immediately ceased to fire, and the special constables,

lushing forward, made several of the band prisoners. The dead were

picked up and laid alongside the bank of the rivulet, and the

wounded were conveyed, with all imaginable speed, to Boughton.

Courtenay was attired in a mackintosh, with abroad leathern-belt —

wore thick overalls on his trousers — had a yellow handkerchief

round his neck, and a white straw-hat. His beard and his hair was

long, and several of his followers were allowing their beards to

grow after his example.

Of the civil force one only was killed, and whether by Courtenay's

second pistol, or by a musket-shot, is not ascertained. His name is

George Catt, He lived at Faversham, and kept a beer-shop. He was a

powerful man, and was supposed to be rushing towards Courtenay, when

the shot passed through his head and killed him instanteously.

Several of the military were bruised with the bludgeons, but Lieut.

Bennett was the only one shot. This young officer had seen some

service in the Burmese war; where, it is said, he distinguished

himself. He had only lately obtained his lieutenancy, and a few days

before his death had returned to the regiment on the expiration of a

leave of absence. His father is an unattached officer, living in

Ireland. The company to which he was attached was not ordered on the

mournful duty, but he volunteered his services, and strongly pressed

for permission to be of the party. We know not with what truth, but

it is reported, that one of his brother-officers remonstrated very

strongly with him against going on the expedition, because he had

dreamed that he (the Lieutenant) had been shot.

The body of the officer was conveyed by the soldiers to the "Red

Lion," and the bodies of Courtenay and his comrades were carried to

the same place, and laid in the stable. On the following day a cast

was made by an Italian tarrying in Canterbury of Courtenay’s head,

when his fine flowing beard and glossy locks were shaven off.

The body was afterward removed to the house, where it underwent a

post mortem examination. The medical gentlemen gave the following

report of his wound.

The ball entered in front of the joint of the left shoulder passed

along under the collar bone, fracturing the first rib, then through

the upper part of the left lung, through the spine, crushing the

second dorsal vertebrae, through the right lung fracturing the

second rib on the right side of he chest. Here the ball took a

backward and downward direction, making its escape from the back

just below the right shoulder-blade.

There was a quantity of extravasated blood on the head above the

forehead supposed to be occasioned by

the blow struck by Milgate. He had also a bayonet-would on the cheek

and a slight abrasure of the skin on the left hand. His skin was

delicately fair, his body very muscular, and his hands and feet

particularly small. There was a great thickness of fat on the

internal parts of the body, and his heart was unusually large. After

being deprived of his hair, it was difficult to recognize any of his

features. Such was the anxiety to possess something belonging to

Courtenay, that his beard was clipped, and the buttons torn from his

clothes, and his shirt nearly stripped from his back before he was

conveyed off the field of battle.

There was nothing very remarkable in the other bodies. They were

clothed in husbandmen's attire, and their features gave no clue of

the agony they must have suffered for the few moments some of them

survived their deathblow.

The body of Lieutenant Bennett lay at the public-house until the

next evening, when it was conveyed in a hearse to the Canterbury

barracks. His fate is universally lamented. He was a very

fine-looking young man, and an only son. He has died with the

reputation of having been an excellent officer and a perfect

gentleman. The shot which killed him made but a slight puncture in

entering his right side, but created a dreadful laceration in

passing out on his left. To look upon his body and behold it

penetrated by the mortal wound by which he died, and perceiving also

that the wretches who had murdered him had, in the rage of the

moment, inflicted a severe blow upon his left temple, one was

inclined in grief and agony, to heap curses on their heads. By this

selfish and base outrage they brought death to many of the ignorant,

murdered so brave and kind-hearted a gentleman as Lieut. Bennett,

and entailed misery upon his family, his connexions, his brother

officers, and upon every one who was acquainted with him.

Another man was discovered in the woods on Saturday. He was wounded

by a bullet, which passed thro’ his throat and out of his mouth.

Three men were reported as found on Sunday; two of them dead. Baker

died on Saturday. Thirty one of the band resided at Herne hill.

Several of the party are still missing; and their friends are

scouring the woods in search of them.

Various causes will be assigned for this riot, and the rioters were

not all actuated by the same motive. That some of the poor wretches

believed Toms, alias Courtenay, to be Jesus Christ, there is no

doubt whatever; numerous instances can be furnished to prove it; nor

is it at all doubtful but that revolution, or rather the war of the

poor against the rich, to obtain by force a share of their property,

influenced others — and this feeling is deeper-seated amongst the

agricultural population than many persons are disposed to believe.

The prevailing sin of ingratitude was never more strongly

exemplified than in the threatened murder of the bailiff, at Dargate,

who, for a great length of time, has paid the labourers good wages,

and has always been ready to recommend an addition to the price of

piece-work agreed on, if the job proved a hard one. In cases of

sickness, or when the men were otherwise prevented from working, he

was always ready to plead their cause and describe their

necessities: and yet these very men not only knew of Toms intention

to murder him, for having declared him to be an impostor and madman,

and for endeavouring to dissuade them from this delusion, but

actually stood in deliberation (within sight of him), as to the

fittest time for Toms to execute his purpose and to destroy the

premises.

The eloquence of the madman was captivating, and many who heard him

have declared that they were nearly carried away by it, against the

conviction of their reason.

It is a fact that Nicholas Mears, the man who was murdered by

Courtenay, was so strongly impressed with the certainty that

Courtenay would kill the first who should attempt to take him, that

when he and his brother were proceeding to the fatal spot, he said

to his brother:— "It is certain one of us must die in this attempt;

which shall it be:" and then almost immediately said, — "It shall be

me — I shall not leave any children." He also bade an affectionate

farewell to his wife in the morning, and said he did not like the

business he was going on, and that he would rather go anywhere else.

It is known by the friends of George Catt, that it was his

intention to have pinioned Courtenay — and that it was in pursuance

of such intention that he availed himself of the opportunity of

rushing at Courtenay the instant he had fired his pistol, and thus

exposed himself to the fire of the soldiers. It is eagerness and

intrepidity had been previously noticed by the magistrates, and

which, most likely, accounts for his being described in the papers

as a constable.

Twenty-five of the prisoners were confined in Faversham gaol on

Friday night, fourteen of which remained until Monday.

On Saturday, late in the evening, two country youths found a

haversack, belonging to Courtenay. There was in it a pistol heavily

loaded, a small hatchet or tomahawk, and other articles. It was

lying a distance of forty rods from the scene of action. The pistol,

with which he killed the officer, has not yet been produced. On

Sunday thousands of people visited the scene of action, and it was

reported that two bodies and a wounded man had been discovered.

There are still five or six missing. Of those engaged, thirty-one

were Herne-hill men.

Previous to Mears’ death Courtney addressed his men at Culver’s, and

said to them, "This is the day of judgment — this is the first day

of the Millennium — and this day I will put the crown on my head.

Behold, a greater than Sampson is with you! If any of you wish to go

home, you may have my permission to go; but, if you desert me, I

will follow you to the furthermost part of hell, and invoke fire and

brimstone from heaven upon you!"

During the whole period of the inquiry, the village of Boughton was

in the highest state of excitement and bustle. On Thursday a

detachment of military were present as guards over the prisoners.

Vehicles of every description, and from all parts, were rapidly

passing to and fro; the connexions of the deceased' were lamenting

their untimely end, and constables and specials were in attendance,

bruised, maimed, and bleeding.

The attendance of reporters for the press, from London, Canterbury,

and other places, was very numerous, and the utmost attention was

paid to their accommodation both by the magistrates and the coroner.

Sir Edward Knatchbull, one of the county representatives, attended

the inquest on Saturday; and afterwards swore in a large body of

special constables. Several thousands of persons visited the scene

of action on Sunday.

The tragic affair has been brought before both houses of Parliament;

in the lords by the Earl of Winchelsea, and in the Commons, by Mr.

Plumptre.

The following lines are said to have been found in Courtenay's

pocket. They are in a female hand:—

"Is it a delusion? No, its peace I hear

"As yet welcome sweet guest

"A passing spiriet softly wispers

"Him safe from harm—and when

"The loud clash of War’s alarm attacks

"Him and boasts the tyrants proudly

"Round him still his manly heart

"Shall know no fear—

"Then sink not oh! my soul nor

"Yeald to sad despair, the cause is

"Great that calls thy Lord away

"A sinking spiriet and a silint

"Tear but ill becomes the child

"Who from the bonds of Satann

"May go free."

INQUEST ON MEARS, THE CONSTABLE.

On Friday morning. Mr. DeLasaux, the Conner, held an inquest on the

body of Nicholas Mears. The Magistrates present were — Rev. Dr.

Poore, N. Knatchbull, Esq., and W. H. Buldock, Esq.

The first witness was John Mears, brother of the deceased. He said,

I am a constable of Boughton, and yesterday morning I went to

Bosenden to execute three warrants, to apprehend William Courtenay,

alias Toms, William Wills, and William Griggs. I went in company of

the deceased and Daniel Edwards to Culver’s house. Saw William

Price, William Burford, Thomas Mears, alias Tyler, and several

others. As he approached near to the house he saw Courtenay. Heard

some one say "Is that them," but heard no answer. Courtenay

approached, and asked who was the constable, and his (witness’s)

brother said "I am." Courtenay put his hand forward, and presenting

a Pistol, fired it, and shot him. Courtenay then struck at witness

with a dagger, but he fell back and escaped. Deceased said "oh

dear!" and held himself up by the hedge for a few moments. Courtenay

in running after witness stumbled, and that circumstance witness

escaped. Edwards was with him; there was a crowd of ten, fifteen, or

twenty persons present. He (witness) then went to Faversham, and

obtained warrants against William Courtenay alias John Toms, and the

others named. He could not recognize more. He then went to the

Magistrates for assistance to apprehend the parties. Dr. Poore and

Norton Knatchbull, Esq., with a great body of persons, accompanied

him back to the place. They went to Fairbrook field, where they

understood the party had assembled. He could here only recognize

Courtenay, who had forty or fifty persons with him armed with

bludgeons.

In answer to a question by Dr. Poore:— Saw to flag.

Re-examination continued:— Saw Major Handley, and his brother, the

Rev. Mr. Handley, pass near the spot at which the rioters had

assembled by the ozier bed. Courtenay presented a pistol or

something at them; he heard a report, and saw a flash from it. The

murder of his brother was committed in the early part of the

morning, about six o’clock. Saw William Wills at the ozier bed, and

Tyler also. Had not seen Wills in the morning. Will is a labouring

man: there was nothing in his hand. Tyler had a bludgeon. They

followed the party to the tile-kiln leading towards Bosenden. He

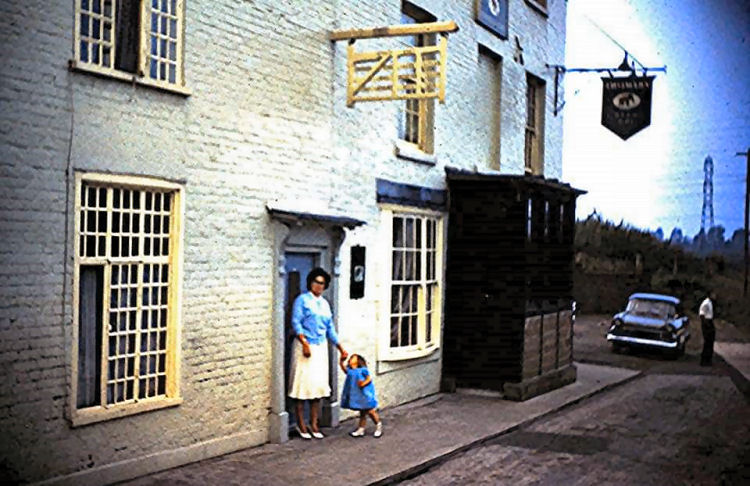

(witness) went to the "Old Red Lion" public house on the turnpike road, and there met a body of soldiers. Courtenay’s men walked in

procession in military order, under the direction of Courtenay, and

formed to the sound of bugle. They marched towards Mr. Francis’s

house. Could not see if they went into the house. They turned round

the woods into Bosenden, to which place witness accompanied Mr.

Knatchbull and the soldiers. There was about fifty soldiers up the

lane. The Magistrates divided themselves among the companies of

soldiers. As they proceeded up the lane they heard a noise in the

woods, and immediately turned up a pathway leading through. Having

proceeded nearly half a mile they saw a body of men. Could

distinguish Courtenay, the two Wraights (the elder of which is

dead), Alexander Foad, Thos. Tyler or Mears, William Wills, George

Branchard, William Rye, — Spratt, Edward Curling, Phineas Harvey,

William Burford, and ---- Griggs. Witness did not recognize any

others. Courtenay had a pistol in his right hand. One of the

military officers approached to arrest Courtenay, who beckoned to

his men, and said "Come on." Sir William presented the pistol, and

immediately fired at the officer and killed him. The officer, as he

was falling, appeared to strike at him with his sword. They were not

a stride apart, when the pistol was fired it almost touched the

officer. The sword struck Courtenay on the head. Heard an order

given for the military to fire, which they did. Wills was very

active in assisting and defending Courtenay. He had a bludgeon in

his hand, with which he struck about him. The whole party came

forward after the firing, and attacked the soldiers and the civil

force violently and with resolution.

By Dr. Poore:— I heard Courtenay say to his men, "Follow me close,"

or something to that effect.

Examination continued:— The men rushed forward, and on the soldiers

firing Courtenay and some others of the party fell.

By Dr. Poore:— The officer fell before the soldiers fired.

Examination continued:— Courtenay and some were killed on the spot,

and others seriously wounded. The confusion lasted a considerable

time, and several were taken into custody. The soldiers continued to

fire until the rioters desisted from attacking them. The officers

gave the signal to cease firing, which the soldiers did immediately.

Daniel Edwards examined:— I live at Boughton; am a labourer, and one

of the Petty Constables of the Hundred. I accompanied Mears, by his

direction, on Thursday morning to Bossenden, to execute some

warrants. When we got there I saw Wm. Price, Wm. Burford, Thos.

Mears or Tyler: they had large sticks or bludgeons of flayed oak,

with nobs. Saw Courtenay come out of Culver’s house at

Bossenden; he

crossed a style which is near the house, and advanced towards us. He

asked "Who is the constable?" Nicholas Mears (the deceased) said "I

be." Courtenay went to him, holding a pistol in his right hand, and

a dagger in his left. He presented the pistol at the deceased, and

shot him. Deceased hung a little while by the railing of the hedge,

and then fell to the ground. Courtenay then took the dagger into his

right hand, and struck at the last witness, who escaped from the

blow. Courtenay then returned to Culver’s house. He came out again.

Nicholas Mears said, "Oh dear, what must I do; must I lay here in

this dishabille." Courtenay answered, "You must do the best you

can." He approached him, and taking his dagger from his left side

with his right hand, struck him three times across the shoulder with

it. I then ran away myself. I was distant from him about three parts

of a rod when this took place. Tyler nodded his head to me to run

another way when Courtenay was running after the last witness. We

were about a rod from the house when Courtenay came up to us. On my

retreating towards the woods I looked round, and saw Courtenay still

striking the deceased with his dagger; and on my reaching the wood I

heard the report of a pistol from that direction. I continued to

walk through the woods, and reached Nash Court, when I again saw

Mears the constable, and accompanied him to Faversham. We returned

to the ozier bed. I saw Courtenay and the three persons before

named, and others whom I should know if I saw them. The men were in

the ozier bed. Heard the report of a pistol, and was told by some

gentlemen to get my gun. I was close by my own house. Heard a horn

sounded, and the men formed themselves info marching order. They

past my house towards Mr. Francis's. I went home, and saw no more

till after the fight. Miss Jane Horn was standing in my garden when

the men passed, but I did not hear any conversation pass between her

and any of the party.

The prisoners, to the number of three-and-twenty, were then passed

before the witness to identify them. He recognized two besides those

named — William Nutting and William Price.

Rev. Mr. Handley examined.— I reside at Hernhill. I first saw eleven

or twelve of the rioters proceeding from the direction of Mr.

Francis’s house towards the osier bed I was in company of my

brother. We rode up to the rioters. I saw Courtenay leave his party,

and advance to another body - some short distance from the bed. He

addressed them, and I could distinctly hear the word "cowards"

repeated. I approached the rioters, and exhorted them to leave

Courtenay, who was guilty of the murder of one of their neighbours,

and told them that they were guilty of high crimes and

misdemeanours, and bringing themselves into great trouble, or words

to that effect. Courtenay returned from the other party, which it

afterwards appeared were the civil force, whom he invited to attack

him; and addressing himself to my brother (Major Handley) or myself,

said, "I will plant a bullet in your breast, sir!"

By a juror:- I was twenty-five or thirty yards from Courtenay at

this time.

Examination resumed:— Major Handley replied, "You are a madman;" and

Courtenay fired a pistol at the Major. Major H. then said, "I wish

to parley with you and your men." Courtenay turned round, with an

insulting movement of the hand, treating the offer with contempt.

The Major then spoke to the men, and told them they were guilty of

high treason. I addressed them to the same effect. We then joined

Mr. Norton Knatchbull’s force. I shortly afterwards saw Courtenay

and his party proceed towards Mr. Francis’s house; they passed me

within about twenty yards, in single file, Courtenay directing them.

I recognised six men by name, and one personally. They were —

William Knight, Thomas Mears or Tyler, E. Wraight the elder, Edward

Curling, Noah Miles, Charles Hadlow, and a youth named Hadlow, whose

Christian name I did not know. I called them by their names, and

asked them to leave the party. I said to Noah Miles, "Have you any

regard for your family?" He said, "I have a regard for my family." I

spoke also to Hadlow and Wraight. From what I saw of the desperate

and resolute conduct of the men, I considered it necessary that the

military should be called in. It would have been imprudent in the

magistrates to advance against them with only the civil force; they

were not sufficiently strong to quell the disturbance, nor to have

apprehended Courtenay and those against whom the warrant was issued.

Mr. Charles Neame, of Selling, yeoman:— I know Noah Miles; I saw him

with Courtenay’s party at the end of Nash Court-lane. He had left

the party immediately after Mr. Handley had addressed them; he said

he was tired of the party, which was then entering the wood. Miles’s

son left with him. I am fully satisfied the civil power was

insufficient to quell the disturbance; it could not have withstood

the force and desperation of the attacks. There would undoubtedly

have been much more bloodshed had not the military been called upon

to interpose. I am confirmed in this opinion by the bold bearing of

the rioters after the fall of Courtenay.

John Ogilvie, surgeon, of Boughton, had, with the assistance of Mr.

Andrews, of Canterbury, examined the body. They found a gun-shot

wound; the ball had entered at the seventh vertebrae, and came out

at the breast, at the seventh rib. In its course it had passed

through the liver, wounding the great vessels and nerves and causing

death. Another gun-shot entered the breast above the ninth rib, and

lodged in the body, but after the most careful examination it could

not be found. There was a wound also on the left shoulder, made by a

sharp instrument, which had fractured the neck of the bladebone; it

was about two inches in length, and one deep. There was also a

slight wound on the left arm. Either of the gun-shot wounds would

have caused death.

The evidence having been brought to a close, the Coroner proceeded

to sum up. All those persons that were in company with the man who

fired were equally guilty with the murderer. Although the hand of

Courtenay was proved to have been the one by which death was

occasioned, all those persons who were sworn to as being seen in his

company namely, W. Price, A. Foad, William Nutting, T. Mears, and W.

Burford, were equally guilty of the offence with Courtenay. Murder

had been defined to be that of a person of sound memory and

discretion unlawfully killing n fellow creature. The jury were not

to inquire to-day whether the party committing this offence was of

sound mind. That would be left for trial by another Court.

After a few other observations, the jury consulted a few moments,

and returned a verdict of "Wilful murder against William Courtenay,

alias Tom, William Burford, Thomas Mears, alias Tyler, Alexander

Foad, Wm. Nutting, and William Price." After which, the Coroner

issued his warrant, and the four survivors, Foad, Nutting, Mears,

and Price, were conveyed to Maidstone gaol, to take their trial at

the next assizes.

INQUEST ON LIEUTENANT BENNETT OF THE 45th REGIMENT. SATURDAY.

Elliott Armstrong, Major of the 45th Infantry, was first called. He

said, in pursuance of an order from my commanding officers to place

myself under the direction of Dr. Poore and other magistrates, I

attended from the barracks at Canterbury, and proceeded on the

London road about four miles, to the "Red Lion" public-house, at Boughton. This was on Thursday the 31st of May, at ten o'clock. A

body of troops, consisting of 100 men, accompanied me, with a

proportion of officers and non-commissioned officers. On reaching

the "Red Lion" I met Dr. Poore, Mr. Knatchbull, and other

magistrates. By their directions I left the London road, and divided

my party into two divisions, — the deceased, Lieut. Henry Bosworth

Bennett, accompanying one division, with Captain Reed at their head,

attended by N. Knatchbull, Esq.; I left the road some distance

higher up with the other division. I proceeded with Dr. Poore about

a mile-and-a-half into the centre of the jungle. When there, a man

in front of us, answering the description of Courtenay, got up out

of the jungle, at the head of a number of others, and I had just

given my men orders to load with ball-cartridge, when I saw the

deceased, Lieut. Bennett, come up on the left flank of us, facing

Courtenay and his men, who were on my right flank. Courtenay’s men

had a white flag with them; I imagined it a flag of truce, and

seeing the men advance and Major Handley coming to me and saying

they were coming to parley, I advanced to meet them. Major Handley

called out "You deluded and misguided men, are you coming to reason

with us." Courtenay made no answer; but, taking off his hat, turned

round to his party, and said "Follow me." During this time deceased

was advancing rapidly towards Courtenay, and Courtenay quickened his

pace towards him. I called out "Fall back, Bennett, fall back," but

being not more than four yards from Courtenay he did not do so.

Courtenay and Bennett nearly closed, and almost rushed against one

another. Lieutenant Bennett raised his right arm and was about to

strike at Courtenay with his sword, when he (Courtenay) advanced

with his pistol in his right hand, ready cocked, and fired. The blow

from the sword and the pistol took effect at the same time. Lieut.

Bennett made another blow or two; he raised his left hand and

immediately fell. I then asked Dr. Poore if I was to fire, but from

the scream of horror of my men at seeing Bennett fall I could not

distinctly hear his answer, but I imagined it was in the

affirmative. I gave directions to fire with ball, and to take

Courtenay and any of his party dead or alive, and the men did so.

Courtenay and several of his men fell. The remainder made a rush on

the soldiers, who had formed into one division under my command.

Courtenay’s men made the attack very resolutely with bludgeons. I

never witnessed more determination in my life; so much so that I was

obliged to order my men to charge with the bayonet to take them

prisoners. This was soon accomplished, and I then ordered the bugle

to sound for the firing to cease, which it did immediately. I gave

the prisoners we had captured into the charge of the constables. In

consequence of the violent attack made by the mob with their

bludgeons several of my men were wounded, many seriously;

particularly Lieutenant Prendergast, who was knocked down by a

bludgeon and severely beaten. I consider the civil power could not

have subdued the mob without the aid of the military. I distinctly

heard the report of two pistols from Courtenay’s party; and I firmly

believe both were fired by Courtenay. I firmly believe that the

constable, Catt, was killed by the second pistol; and the more so

because I believe him to have been out of the line of the soldiers

fire when he fell. I can identify as being present William Wills,

Stephen Baker, Thomas Griggs, and George Branchett. I never saw a

more furious or mad-like determination in my life than I witnessed

in the attack by Courtenay’s party.

The Rev. John Poore, D.D. of Murston, Sittingbourne, examined:— On

Thursday morning last, in consequence of the riotous proceedings of

a person calling himself Courtenay, and others, and of their

desperate conduct in shooting a constable named Mears, in the

execution of his duty, and considering it impracticable for the

civil power, unaided by the military, to arrest them, I applied to

the commanding officer of the 45th regiment of Foot, quartered at

Canterbury barracks, for their co-operation. The military were some

time before they arrived. I proceeded towards Canterbury to meet

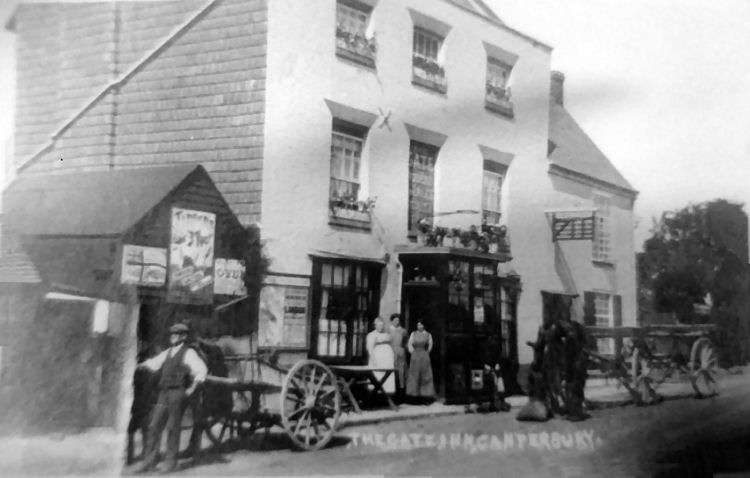

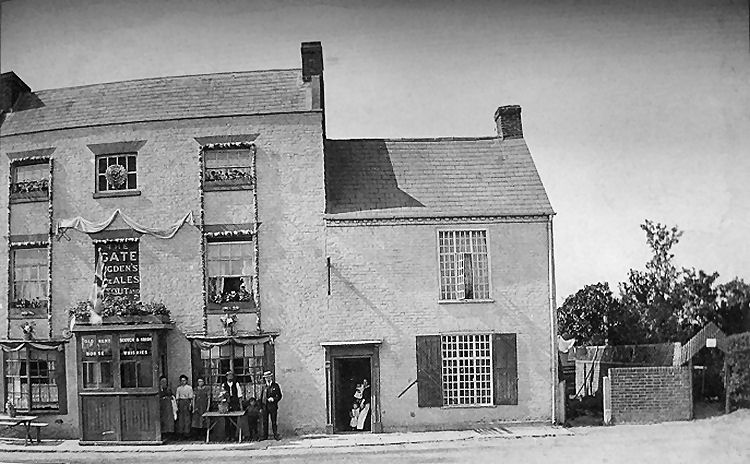

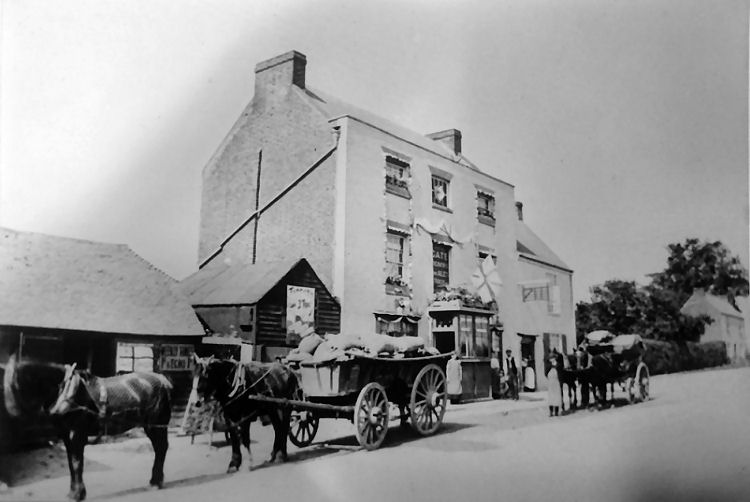

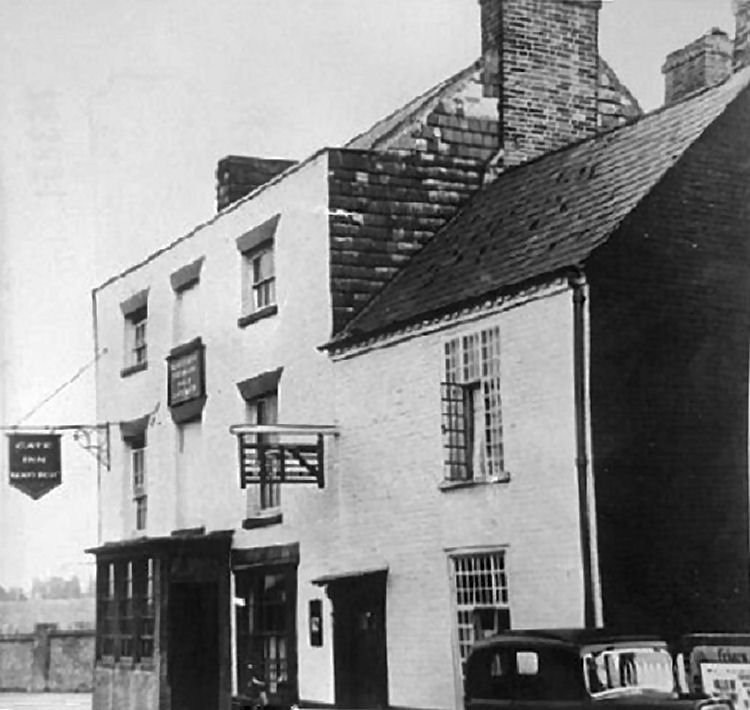

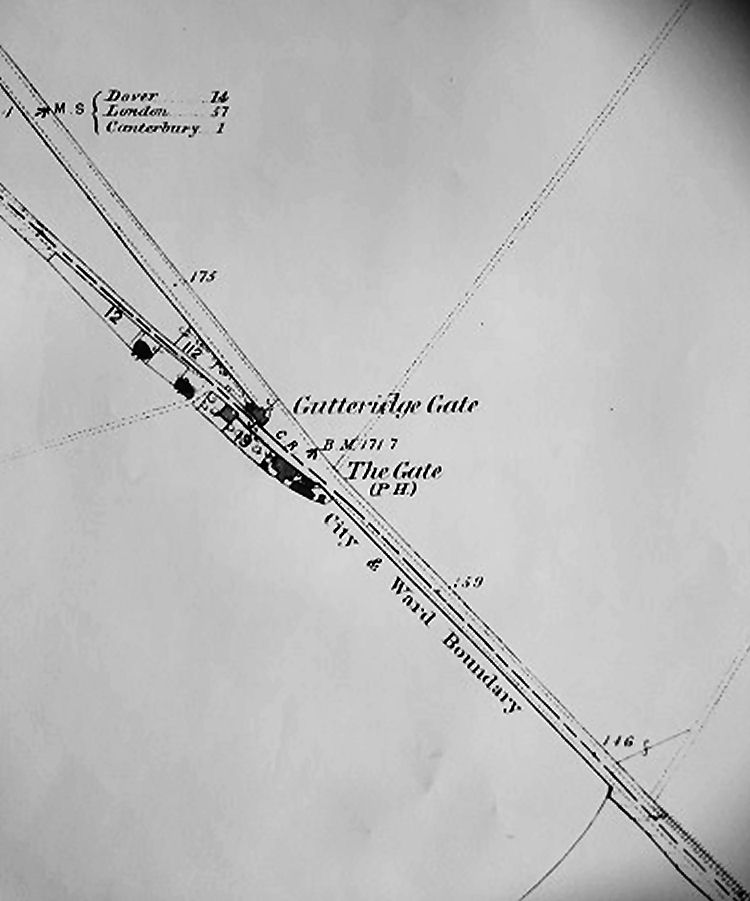

them, and met them near the "Gate" public-house. I immediately

communicated to Major Armstrong the desperate conduct of the party;

expressed my opinion that, whoever came first into contact with

Courtenay would be shot, and said he must be taken, dead or alive,

and his party dispersed; and that I hoped it would be done without

effusion of blood. The witness then described the division of the

troops as stated by the major. He (witness) accompanied one division

down the Barn road leading into Blean Wood. After proceeding a mile

and a half further we received information, on which Major Armstrong

halted, and asked me if the soldiers should load. I said

"certainly;" and the order was given to that effect. The cartridges

were tied in bundles, and were not ready for immediate use; and this

circumstance occasioned a slight delay. I then observed Courtenay,

and about forty or fifty men with him. They had a white flag near

the front, and Courtenay was at the head, with a pistol in his right

hand. He called out to his men, "Boys, come forward, and don’t

behave like dastardly cowards," or similar words. At this time Major

Handley rode forward and called to Courtenay's followers— "Good men,

he is deceiving and deluding you — he is leading you to destruction;

are you open to reason," — or words to that effect. Immediately

afterwards I saw the deceased (Lieutenant Bennett) close by

Courtenay. I heard the sound of a pistol, and the deceased fell. I

then heard Major Armstrong call to me, "Dr. Poore, where are you?" I

ran towards him, and the troops began firing. The result was that

Courtenay and several of his party were shot, and others taken

prisoners. I saw Courtenay’s party attack the constables and

soldiers. I saw Wills attack and strike Major Armstrong with a

bludgeon. When the riot was quelled, I took down upon the spot the

names of the following parties, who were either dead, wounded, or

taken prisoners. Killed on the spot — William Courtenay, Edward

Wraight, Pheneas Harvey, George Branchett, William Burford, William

Forster, George Griggs, and William Rye. Wounded taken prisoners —

Stephen Baker, Henry Hadlow, Alexander Foad, and Thomas Griggs. The

other prisoners were, Edward Wraight, John Edward Curling, and Sarah

Culver.

Thomas Milgate, a coach porter, of Canterbury, examined:— On the

31st of May I went towards a wood called the Blean, and observed

several gentlemen on horseback. They said it would be as well to

watch the movements of Courtenay’s party to prevent their escape. In

consequence of this I accompanied Robert Little, the Superintendent

of Police of Faversham, and proceeded a short distance into the

wood, and then separated, I taking the extreme left of the party.

Having gone a quarter of a mile I came directly upon them. I saw

about forty lying down in a circle, Courtenay being in the centre,

with a flag planted near him. When I was observed Courtenay started

from the ground, and said, "Up, men." He held a pistol in his right

hand, and said to me, "Move no further." Two other young men with me

retreated into the woods, hallowing all the time as loud as we

could. Mr. Little and others then joined us. We remained quiet for

some time, expecting the soldiers to come in behind us. A body of

soldiers did come in front of us, and drew up in a line. Courtenay’s

party laid down after I left, but on seeing the military they all

rose again. Courtenay said something to them, but I could not hear

it. Courtenay faced the military, and his men then marched one by

one towards the troops. I saw Lieut. Bennett at the extreme left of

the troops, and Courtenay and he advanced towards each other.

Courtenay turned towards his men, and they approached and formed

nearly a circle round the two. Some gentlemen then rode forward, and

begged of Courtenay and his party to desist, and not lead the poor

men on to destruction; they made no reply, but Courtenay said to his

men, "Come on, my brave fellows; keep close." The men not coming on

so quick as he wished, he again said. "Come on, my men," apparently

in a passion. I got nearer the officer, and the officer got nearer

to Courtenay. When about two rods from the officer Courtenay ran and

sprang over a stump of a tree towards the officer, and going up

close to him with a pistol in his right hand, and a bludgeon in his

left, he placed the pistol close to the officer's body and fired.

The officer immediately struck at Courtenay with his sword, and

Courtenay staggered; but whether struck, or to avoid the blow, I

cannot say. The officer staggering, several of Courtenay’s men

struck at him as he was falling. I recollect Wills as next to

Courtenay. I, and one of the men before mentioned, who is dead

(Catt), stepped forward, and with a bludgeon given me by a Mr. Pell,

struck Courtenay on the head. He staggered back, but whether he fell

I can’t say, as I was knocked down directly. I saw Courtenay

standing just above me; the guns began firing, and Courtenay was

shot and fell down close by me. He was, just before shot, fighting

with Little and others. I was again violently struck with a

bludgeon, partly on my thumb and partly on my bludgeon. I got up,

and the man who struck me ran away. I cannot swear to him. When I

got up I saw two men coming towards me. I seized one of them, and

the other Mr. Little took. The rioters were soon after dispersed.

Edmund Foreman, of Hernehill, a wheelwright, having been examined,

Bartlett Allen Chambers was called. He is a constable of Faversham,

and took John Silk into custody. He received a gun-shot wound while

taking him.

Robert Little examined:— I reside at Ospringe, in the parish of

Faversham, and am superintendent of the police. I saw Edward Wraight,

jun. and Alexander Foad in Bossenden-wood; took them into custody.

Foad was wounded in the mouth while fighting with me. I saw Sarah

Culver in the wood, and sitting with Courtenay in the circle, with

the flag between them. I know her by her bonnet. When the affray was

over, I said to the constable that was with me, "There is a woman in

the wood — don’t let her go." After the officer was shot I ran into

the centre of the mob, and struck down Edward Wraight. Edward

Curling struck at me, and so did Alexander Foad. William Wills I

captured, with a flask, now produced, full of powder. John Spratt

and Thomas Tyler Mears acted with great violence. William Wills had

a pistol in his right hand as he entered the wood at Tile-hill, near

Boughton-hill.

Thomas Andrews examined:— Is a surgeon, residing at Canterbury.

Examined the body of Lieutenant Bennett, assisted by Mr. Ogilvie.

Found a gun-shot wound on the right side of the chest, passing

through the right lung, running completely through the heart, and

making its exit on the opposite side of the body. The wound caused

instantaneous death.

Benjamin Jacobs examined:— Resides in St. Peter’s-lane, Canterbury,

and is a general dealer. Went into Bossenden-wood on the morning of

the 1st of June (Friday), at ten minutes past seven, and near the

spot of the riot found the following articles, produced:— A brown

camlet cloak, lined with green baize; then a blue bag, containing

nearly two hundred matches; a leather bag, containing about 140

leaden balls of different sizes; a piece of oilskin; a pair of

boots, maker’s name, "Goldsmith, Watling-street, Canterbury, 1834;"

a Mackintosh cape; a flannel jacket; and an old newspaper — the

Evening Mail of July 29, 1831.

William Exton examined:— Early on the same morning I found in the

wood a leather pistol case, with hare-skin flap; one cotton glove, a

blue jacket, a waistcoat, two short gaberdines, and a burning lens

in a tin case.

John Ogilvie, surgeon:— Resides at Boughton. Corroborated the

testimony of Mr. Andrews.

Some doubts were raised as to the woman Culver being in the midst of

the party, and Milgate and Little were again questioned. Milgate did

not see her.

The Coroner summed up in a few words, having laid down clearly

yesterday the points for the consideration of the jury. They would

bear in mind that it was sufficient for their verdict that the

parties before them should have been proved to be present with this

deluded and deluding madman. With respect to the woman Culver there

might be some doubt, it appearing that a woman was there, and her

name might have been Burford.

The jury retired for a short time, and on their return the foreman

pronounced a verdict of wilful murder against William Courtenay

alias Toms (dead), Edward Wraight the elder (dead), Edward Wraight

the younger, Thomas Mears alias Tyler, James Goodwin, William Wills,

Win. Forster, Henry Adlow, Alexander Foad, Phineas Harvey, John

Spratt, Stephen Baker, William Burford, Thomas Griggs, John Silk,

George Branchett, Edward Curling, George Griggs, and Win. Rye. —

Sarah Culver, Wm. Spratt, and Samuel Eve, they did not consider

sufficiently identified, and they were detained in custody to answer

the general charge of misdemeanour.

FUNERAL OF LIEUT. BENNETT.

At five o’clock on Saturday afternoon the burial of this lamented

officer took place at the Cathedral. The avenues leading to the

place of interment were thronged with spectators, who appeared to

sympathise in the dejection and sorrow which marked the countenances

of the soldiery. The procession was headed by the light company,

carrying their arms reversed, followed by the band, the drums

muffled, and playing solemn dirges. The undertakers, Messrs.

Bellingham and Mr. Kelson, builder, walked next, and preceded the

coffin, which was covered with black cloth, six of the deceased's

brother officers bearing the pall. The chief mourner, Lieutenant

Colonel Boys, walking behind, closely followed by the rest of the

officers of the regiment. The remainder of the 45th followed without

their fire-arms. The procession entered the south western entrance

of the cathedral, proceeded up the centre aisle of the choir, and

through the sanctuary into the cloisters. On entering the sacred

edifice several of the prebendaries and minor canons met the body,

and the Rev. W. F. Baylay read, with much solemnity, the beautiful

funeral service. The grave was on the southeast side of the

cloisters, and the coffin having been lowered into the silent tomb

and the service concluded, the light company fired three times over

the grave. The soldiers then retired in the same form as they

entered, and marched back to the barracks — the band playing

military airs. The cathedral was thronged to excess, but the utmost

order prevailed, — every one being impressed with the awfully tragic

end of the lamented deceased.

MONDAY (YESTERDAY), June 4.

INQUEST ON GEORGE CATT.

Before entering into this melancholy catastrophe, Mr. Shepherd, at

the opening of the Court, addressed the jury in the following

terms:— "Gentlemen, — I produce a letter to the jury, directed to

one of the magistrates, General Gosling, Ospringe, Kent, who is

absent; but his son opened it and forwarded it to me. I mention

this, that it may go forth to the public."

(copy).

24, Marshal Street, Golden Square, June 2, 1838.

Sir, — Having seen, through the medium of the public papers, an

account of the fatal riot near Canterbury, I beg to state that I

know well the person assuming the name of Sir William Courtenay, and

that his real name it John Tom, a native of the town of St. Columb

Major, in Cornwall; and that I also knew his family, having been

brought up in the same town. — I am, Sir, your’s most obediently, G.

B. ROGERS.

"I also beg to state that on Saturday evening a bundle was brought

to me — viz. a leathern wallet containing a laden brass blunderbuss,

a pistol laden with ball, a hog knife, sharp, and ground up fresh, a

hatchet, also recently ground, a large bundle of matches, a flute, a

jacket, a bible, a bundle of string, a perfectly new belt for a

brace of pistols, a cavalry sword with sharp edge, and a pistol

case.

The Coroner then proceeded to examine evidence touching Catt’s

death.

Stephen Champ, a labourer, residing in St. Mildred’s, Canterbury,

was first called. He said — I saw the deceased, George Catt, in

Bossenden-wood, acting as constable, on Thursday, the 31st of May.

Saw Lieutenant Bennett in front of his detachment; he went up and

met Courtenay; Courtenay was advancing to Bennett. Some words were

spoken by Lieutenant Bennett, but I did not hear them; they were

addressed to Courtenay. Saw Courtenay lift his hand and fire the

pistol. Heard the shot; they were quite close. The Lieutenant fell

directly. Lieutenant Bennett had a sword in his hand. He did not

strike any one else; if he had struck any body else, I was close

enough to him, and must have seen him do it. There was no person

within the reach of Bennett but Courtenay. Lieut. Bennett was the

first man who fell. None of Courtenay’s men were near to

Bennett before he fell. Catt was at his (the officer’s) right hand,

and I think the soldiers shot him by accident.

Thomas Millgate examined:— Is a coach porter, residing at

Canterbury. Saw Lieut. Bennett in Bossenden wood on the 31st of May

advance towards Courtenay. Courtenay was advancing rapidly towards

Bennett, and when within two strides of him presented a pistol with

his right hand and shot him, he staggered, striking at Courtenay,

and then fell. Bennett did not strike any body before he fell. None

of Courtenay’s people were near enough for Bennett to strike them.

Courtenay was scarcely near enough for the sword to reach him; and

Courtenay was half-a-rod in advance of his followers. Saw Catt after

he was dead. I consider he was shot by the soldiers, from the

position in which he was running. I believe him to have been shot by

accident.

Question by the Coroner:— If any body was to come before me to-day,

and say that Bennett had run a man (one of the mob), through the

body before he fell or was shot, should you think he was telling the

truth or not?

I should consider he would perjure himself if he did so.

I did not hear more than one report of pistols from Courtenay’s

party.

John Ogilvie explained the nature of the wound, which is much larger

than either Mears or Bennett’s.

[This answer was elicited to do away with the impression of Catt’s

having been shot by Courtenay, and not by the military].

Henry Ashbee, Colking Farm, parish of Boughton, yeoman, examined:—

Was in Bossenden wood on 31st May. Saw the commencement of the

affray. Saw the mob headed by a person calling himself Courtenay.

Saw the officer that was killed there; he was leading a detachment

of soldiers. Saw him leave the soldiers and advance towards the mob.

Saw Courtenay come forward towards the officer. He said to his men,

"Come on my men, prove yourselves men, and not cowards!" He was, at

this time, leading them in a contrary direction to Bennett. Shortly

afterwards Courtenay approached Bennett. He appeared to have a

pistol in his left hand — at least, this is my opinion. He had a

light stick in his right-hand. I mean a white stick, a club. I am

certain that the bludgeon was in his right hand, as he flourished it

over his head. When the pistol went off it appeared to go over

Bennett’s head. Bennett, as Courtenay came up, struck at Courtenay

with his sword; but very faintly. Bennett appeared to endeavour to

strike up Courtenay’s pistol, and in doing so overshot

himself, and the sword went up in the air, and fell faintly over his

shoulder. Bennett was surrounded by the mob immediately, and my opinion is

that Courtenay’s pistol missed Bennett, and that one of his people

rushed forward and shot him just as he was about to strike

Courtenay. I was within ten paces of Courtenay. No one was near

enough of Courtenay’s party to be reached by a sword in the hands of

Bennett. Catt was, undoubtedly, shot accidentally.

Mr. Ashbee said that Milgate was mistaken in saying he struck

Courtenay, as he considered that Milgate was not nearer at any time

to Courtenay than three paces.

Thomas Andrews, surgeon, &c. corroborated Mr. Ogilvie’s statement.

The deceased was shot by a musket-ball, and not a pistol, as his

wound was much larger than either Mear’s or Bennett’s; and unless

the pistol was close to his mouth, it could not have made so large a

hole as a musket.

The Coroner left it to the jury to decide the point at issue. They

returned the following verdict — "We unanimously consider George

Catt was shot by the military by accident, while in the execution of

their duty."

An extraordinary scene was witnessed by the appearance of Mr.

Church, surgeon, of Sittingbourne, who stated he considered

Lieutenant Bennett struck one of Courtenay’s party before he (Mr.

B.) received his death wound.

The Jury found a verdict of Justifiable Homicide in the cases of

nine of the Courtenay party, who died from their wounds; and having

complimented the Coroner upon his impartiality, and expressed their

intention to recommend all the prisoners to mercy, the painful

investigation terminated.

|