|

Sheerness Guardian 12 November 1859.

MYSTERIOUS AND MELANCHOLY OCCURRENCE. DISCOVERY OF THE BODY OF A

FEMALE IN THE MOAT.

Considerable excitement prevailed in this town on Monday last, owing

to the discovery of the body of a young, neatly-attired, and

prepossessing-looking female, found drowned under somewhat

mysterious circumstances, in the outer moat, adjacent to the

recreation ground, and forming part of the entrenched fortifications

of Sheerness.

The body was discovered between 8 and 9 o'clock in the morning and

had evidently been in the water several hours. Life of course was

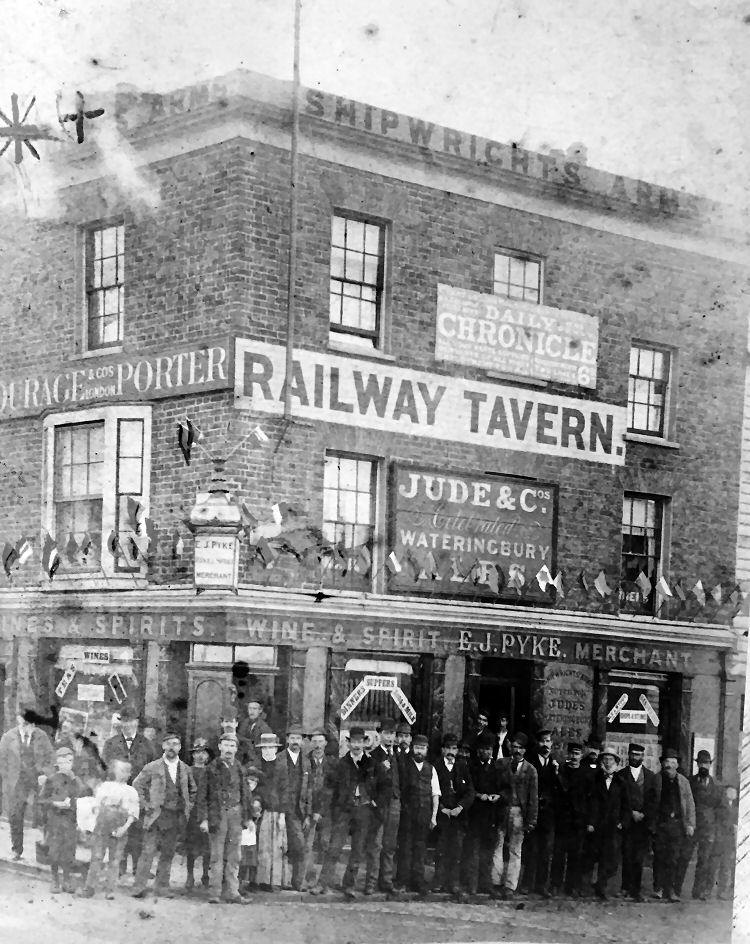

extinct. After being taken from the water and removed to the

"Shipwright's Arms," in Mile Town, speculation became rife, as to

who she was, — what she was, and whence she was.

Was she

"One more unfortunate

Weary of breath,

Rashly importunate

Gone to her death?”

or had she been accidently drowned?

These very natural enquiries were not long without an answer.

On the girls person wire found a purse containing nine-pence, a

handkerchief, a pair of kid gloves and a small tradesman's account,

on which was the word "Paine," The possession of this latter

document, suggested to the police to make such inquiries, as led to

the discovery that the name of the deceased was Elizabeth Pain —

that she was 19 years of age and that she was the daughter of a

carpenter and joiner, living in Hope-street, of the name of Henry

Pain; also that she had been absent from home the whole of the

preceding night, having left home about six o’clock on Sunday

evening, with the intention of going to church or chapel.

When the body was first discovered and taken from the water, the

lower garments of the girl’s wearing apparel were floating above her

head, but whether they had been blown over in the water, or blown

over as she was thrown in, or threw herself, into the water, remains

as great a mystery as the fact, whether she really did drown herself

or was accidently, or otherwise drowned. The only thing certain, is,

that she was found drowned, but as is usual in such cases, public

curiosity and conjecture is only highlighted by the fact, that the

occurrence is involved in mystery. This mystery is still further

increased by certain extraordinary circumstances (given (given in

the subjoined evidence,) which transpired between her and her

alleged sweetheart, on Sunday evening, and also from the fact that a

deep incised wound was discovered on the girl's forehead, which had

evidently been made as the body fell into the water, and which was

sufficient to produce instantaneous insensibility. This latter fact

is sufficient to show that if the deceased had accidentally fallen,

or been blown into the water, (as is urged, might have been the

case), she would have been incapable of self-rescue. The most

charitable interpretation is, that she accidently met with a

premature death, but on the other hand, there are certain strange

and unaccountable features in her conduct on Sunday evening, which

would suggest the formation of a different opinion, and that in a

fit of grief or remorse, on account of unrequited love disappointed

hopes, or from some other unexplained cause, she actually committed

sell-destruction. We shall not however argue the question, as the

evidence, which we have given in full, is insufficient to prove

either premises. We leave our readers to form their own opinions on

the subject, from what was said on the inquest and from which may be

gleamed all the information that is strictly attainable.

We cannot notwithstanding, but refer to one or two facts antecedent

to the occurrence, which affect the case in forming a judgment upon

it, and these are — that when deceased left the company of a female

companion, between eight and nine o’clock on Sunday evening, "she

was very cheerful and well," but that an hour or so subsequently,

after she had been in the company of a young man of the name of

Murphy, to whom she had recently, if not at the very time of the

occurrence, stood in the relationship of a sweetheart, she

manifested the greatest distress and misery. Why such a sudden

transition from gaiety to grief took place, has not transpired, -

why she should resolve upon staying out all night has not been

satisfactory answered, and it is to be regretted that it was not

elicited at the inquest, whether any quarrel or rupture of

friendship took place between the two, during their extraordinary

interview, which would justify the public in coming to the

conclusion, that the circumstances connected there with, were

sufficiently aggravated or affecting, to lead anyone to commit an

act of self-destruction. This evidence is wanting, that perhaps

Murphy himself, may feel prompted to supply it, or otherwise the

judgment must err in coming to any definite conclusion. The conduct

of Murphy himself is equally inexplicable, if not mysterious. He was

with the girl on Sunday evening until 11 o'clock, and then left her,

on a cold, bleak wintery night, and sheltered, unprotected, and in

agony, and within a few feet of the water on the beach, and as he

himself admits, with a fear in his mind that she might attempt to

drown herself, basing as his only motive for doing so the fear of

his being locked out and having to storm the inclemency's of the

night, as weightier than the fear of the girl being exposed, or any

or of any ill befalling her. Very rightly, as everyone will admit,

the jury felt it to be their duty to censure his conduct, and the

coroner to designate it, at least, "unmanly."

THE CORONER'S INQUEST.

Was held at the "Shipwright's Arms."

The jury consisted of Mr. Brightman, (foremen), and Messrs. S. C.

Bassett, W. Holmes, W. Edgecombe, J. Berry, E. Troughton, S. Hooker,

C. Polson, A. Filmer, G. Hogben, A. W. Howe, and R. Seager.

The Coroner in opening the proceedings, said, that as some 50

different reports were current, as to the facts of the case into

which they were called to inquire, he trusted that the jury would

form their opinions solely on the evidence which would be produced.

The jury then proceeded to inspect the body which was lying in an

outhouse in the "Shipwrights Arms" yard. The appearance of the corps

was remarkably fresh; the bloom was still on the cheeks, and the red

had not departed from the lips, - the beauty of a fine countenance

being marred only by the deep scar over the eye-brow, and from which

blood had freely flowed and disfigured the face.

The jury afterwards reassembled, when the following evidence was

produced.

The first witness called, was Henry Pain, (the father of the

deceased.) He appeared deeply affected, and deposed that he was a

carpenter and joiner. He had seen the body and it was that of his

daughter. She was 19 years of age and lived with him. The last time

he saw her alive, was on Sunday evening, on which night she went out

at six o'clock to go to Chapel, but never returned. He knew nothing

as to the cause of her death.

Mr. Holmes, enquired whether she had stayed out on previous

occasions?

Witness said, that the only time she was a late, was about three

months ago, when she stayed out until half past 9 o'clock, when he

said to her, "you have no business to be out so late. I don't think

that chap means you any good."

In reply to Mr. Bassett, as to whether he was aware of her being so

late on Sunday evening, he said he knew she was not at home; - that

they waited up for her and that she went out with a young woman with

the intention of going to Chapel.

Charles Yelland, (a photographic artist), was the next witness. His

evidence went to show that as he was coming over the draw-bridge

towards Blue Town, about 20 minutes past eight o'clock, on Monday

morning, he saw a woman standing on the bank of the moat, about 20

or 30 yards distance. He at first thought she was going to drown

herself, from her manner and appearance, as she was ringing her

hands and here hair was blowing about her head. On speaking to her,

she told him there was something in the water, but she did not know

what. He jumped over the fence and saw the deceased in the water,

some three or four yards from the embankment. He then undressed

himself of all accept his shirt and with the assistance of another

man, (Mr Floyd,) got the body out. When found the deceased was lying

on her face, with her feet towards the bridge, and her clothes over

her head as if they had been blown over by the force of the wind. He

did not know whether there were any footmarks to show that there had

been any struggle.

In reply to certain questions suggested by the jury, the witness

said that the depth of the water was about three feet, and that

there were three large stones in it, lying at separate distances

near to where the body was found. He could not say whether the body

was floating or not, as the face was downwards. There was a cut

above the left eye, but no signs of blood on the face until the body

had been moved, when blood began to flow freely.

Jane Welch, (the female referred to by the last witness), was next

called. She said that about half-past 6 o'clock, on Sunday evening,

as she was passing near to the bridges, the wind (which was very

high at the time), carried her Victorine away. On Monday morning,

about 8 o'clock she went to look for it in the moat, when she saw

something in the water and thought it might be what she was looking

for, but on a closer examination, she saw that it was something like

female petticoats. She called to some men who were passing, and the

body of the decease was taken out of the water. She did not notice

any foot-marks on the bank.

Mary Ann Smith, was the next witness. She is a single woman, about

the same age as the deceased, and was one of her acquaintances. Her

evidence was as follows:- "I went out with Elizabeth Pain, on Sunday

evening, about six o'clock. We walked up and down Mile Town, for a

little while, and then we went to Blue Town. We then returned to

Mile Town, as far as the Wesleven Chapel, but we did not go in.

Whilst out we met John Pain, a cousin of the deceased. The deceased

had a little conversation with him, but I did not hear what it was

about.

When we left him, we went into the High Street again, and in coming

down the street, we met a young man named Arthur Murphy. I left the

deceased with the young man and went on. I did not see what became

of them afterwards. I left them between eight and nine o'clock. I

did not know much of Arthur Murphy, but as the deceased was walking

with me on Sunday evening, she said she wished she could see him. As

she said so, I thought I had better leave them. I did not hear any

conversation that took place between them. When we went out, we went

out for the purpose of going to church, but being late, we walked

about the town instead.

The Coroner enquired what time service commenced at the churches in

Sheerness, as they would surely be in time if they left home at the

time named? In reply it was stated that they commenced at half-past

six, but that the deceased after leaving her own residence, had gone

to that of the witness, and stayed there about a quarter of an hour.

By Mr. Edgecombe:— Did the deceased appear cheerful and well when

you left her?

Witness:— She was very cheerful and well when she left me.

In reply to other enquiries, witness said that the night was windy

and that rain fell before she reached home, but it was not dark. She

went home about nine o’clock.

Arthur Murphy, was then called into the room, when the Coroner told

him that if he wished to be examined he could, but he was not

necessarily bound to answer any questions, nor to say anything that

might in anyway criminate himself. He, (the Coroner), gave him this

caution as a mere matter of form, not that he presumed it was

necessary. Murphy was then sworn and said,—

I am an assistant coppersmith. I know the deceased, and was on

friendly terms with her. I met her on Sunday evening, in Mile Town,

about half-past eight. She said, "where are you going?" and I

replied, down the street. She said, "come with me." I stood talking

with her for about ten minutes and then went down the street with

her. She said she was going home, but we went as far as the "Hotel"

fence, in Banks' Town. Her proper way home was down Hope street,

but she said she would go along Banks' Town, so that her father

might not see her. When we got to the end of the "Hotel" fence, it

began to rain, and we stood under the fence nearly an hour. When it

left off raining, I asked her to go back by the same road, but she

said she would not go that way, but round by the back of the

"Hotel."

We went round by the back of the "Hotel" until we came as far as

Beach-street. I wanted her to go down the street and go home, when

she said "no," she had stopped out so late, she would not go home all

night? It was then about half past nine or from that to ten o'clock.

She said she would go across to the sea-wall. I went with her as far

as the gun-house, near to the "garrison-point." I then said to her,

I would go no further, and I wanted to turn back, but she would not

come. I stopped with her some time and tried to persuade her. I

stopped until I heard the clock strike a quarter to eleven. I had to

be home at eleven, as my landlady told me when I went to lodge with

her, that I should be kicked out if I was not home by eleven. I said

I could not stay there all night, and had gone a short distance from

her, when I locked round and saw her going towards the water on the

beach. As I was afraid she might go into the water, I went back to

her, and when I want up to where she was she was sitting down

crying. I stopped there a short time trying to persuade her. But it

was no good, and I left her there. She was sitting down about three

or four yards from the water when I came away. Before leaving her, I

asked her what she meant to do with herself, and she said she meant

to go to Chatham in the morning, and from thence to London, to her

aunt, After I left her, I saw nothing more of her."

By Mr. Holmes:— Did you report to any one that you had left her

there?

No.

Nor tell her father?

No.

She told me her father had smashed a likeness she had of mine.

By Mr. Brightman:- What made you think she was likely to go into the

water?

She was crying and fretting, and I did not know what she meant to

do. She was unhappy about staying out so late.

By Mr. Edgecombe:— Did she tell you what she was crying for?

No Had you no idea? I believe she was suffering from her father

having objected to her keeping company with me.

Mr. Brightman:— And you left her there?

I did. (strong sensations and manifestations of indignation.)

Mr. Brightman:— It was a very cruel thing, (approval).

Witness:— I told a mate when I went home, where I had left her, and

he said it was a very foolish thing, as she might drown herself.

By Mr. Troughtman:— Do you mean to say you were with the girl so

long and did not ascertain why she was crying and so distressed?

She told me that some one had told her father something defamatory

of my character and conduct, and also about being guilty of knocking

about Blue Town, with improper characters, which is untrue. In reply

to other enquiries, witness stated, that it was fine weather when he

left the girl, and that they had not taken shelter in the gun-house.

By Mr. Holmes:— Were you engaged to the deceased?

Witness:— I did keep company with her some time ago, but we had a

quarrel, and she has since been keeping company with another person;

but on Thursday night, she came up to me and struck me in the breast

and said, "won't you speak to me?" I went down the street with her

and we passed two bad girls. She said before another week was over,

she should be as bad as they were.

Mr. Edgecombe tried to elicit whether the witness had ever so far

committed himself, as to have taken advantage of the girl's

affection for him, but the enquiry was suppressed.

Mr. Brghtman said it appeared that the witness had not paid the girl

that attention, which she had affection for him.

The witness was then removed; Sergeant Ovenden stating that what he

had said with respect to his "mate" and the time of his going home,

could be confirmed by the young man mentioned, if necessary. The

jury thought it unnecessary.

Major Kirkby Robinson, (surgeon), was then sworn. He said:— I was

called to examine the body of the deceased on Monday morning. I

found one external mark of violence, in the shape of a contusion and

lacerated wound, situated on the left upper eye-lid, immediately

beneath the eye-brow, which might have been caused by the deceased

coming in contact with a hard substance, such as a stone, during a

fall, or otherwise being thrown against it. There was no other

external mark of violence. The body presented the appearance of a

person having died from suffocation by drowning. That in my opinion

was the cause of death. The wound was produced before drowning took

place, and might have stunned her. She appeared to have been in the

water some six or eight hours.

A long conversation followed, in which both the coroner and jury

took part. The Coroner suggested the possibility of the girl being

carried off her feet by the gale, as was the case with a woman in

London a few days previously, who cried out for help and could not

save herself. It was also urged if she had jumped into the water,

she would have gone clear of the stones and not have sustained the

laceration on the eye brow. It was also submitted, that in walking

along, she might have been crying and have fallen down the wall, and

that, if the clothes blew over her head, and she became entangled

in them, it would be a difficult matter to release herself.

The whole of the jury considered that the conduct of Murphy in

leaving the girl, deserved their censure.

The Coroner then briefly addressed the jury. He observed:— "After

the evidence you have heard, I think I can easily leave the matter

in your hands. Whatever opinion you may entertain as to the motal

culpabdity of Murphy in leaving this poor girl, it is merely for you

to decide and to say, according to the evidence you have heard, how

she came by her death. There is evidence to show she was drowned,

but how, you cannot say. There is no evidence to show that. We have

evidence to show that people have been blown into deep water and

drowned, but in this case there is no such evidence to prove that

this was the case, or any evidence to show how she came into the

water. It is therefore for you to return a verdict "that the

deceased was found drowned, but that there is not sufficient

evidence to show how."

The jury concurred and a verdict was returned accordingly.

Mr. Hogben suggested that the jury should express very strongly

their disapproval of Murphy’s conduct. The feelings of common

humanity would have dictated to the greatest stranger, to have

stayed with the girl, still more one who stood in such a

relationship to her and who had witnessed her distress. He ought to

be severely reprobated.

Other gentlemen spoke to the same effect, and the Coroner expressed

himself happy to obey their wishes. As a matter of law it did not

affect the case, but as a matter of feeling it did.

The witness Murphy, was then re-called, when the Coroner thus

addressed him:— "I am requested by the jury to convey to you, the

feeling of disgust which they entertain at your conduct towards this

poor girl. They think it would be unmanly conduct on the part of any

man, under any circumstances, but more especially on the part of a

man who stood in some relation to the girl as a sweet heart. It will

be a reflection — and a very painful! reflection to you, for many

years, to know that you have acted as you have done. Although there

is no legal responsibility attached to your conduct, there is a

great moral responsibility under the circumstances. I leave you to

your feelings which will, I trust be punishment enough.

Murphy said that he had done the bent he could. The jury then

dissolved, having before leaving, subscribed about 30s. towards

assisting the father of the girl, in defraying the expenses of her

funeral.

In reference to the above melancholy event, several letters have

been sent to us, expressing varying opinions as to the cause of the

occurrence. One of our corresponding remarks:— "The painful

circumstances have given rise to many opinions, as to how the young

woman came into the water. As for myself, I have sufficient charity

to think, that she did not drown herself, but that she was

accidentally curried into the water by the wind inflating her dress

— which was blowing very strongly on Sunday evening — and that her

face was cut by her falling against the stones. Our correspondent

afterwards makes the following comment:— "The moat is certainly very

unprotected, and if the suggestion of Mr. John James Young, made

about three months ago, to plant a Tamarisk edge around the bank,

was carried out, it would, in about three years, prevent accidents

of such a nature; and, at the same time, form an ornament to the

Recreation Ground." In conclusion, he expresses a hope "that Mr.

Young will be supported by the public in his endeavours to carry out

this proposal; and that although it will not avert what has

happened, it may be the means of preventing future accidents."

|