|

From the Dover Express and East Kent News, Friday, 17 February, 1905. Price 1d.

PROSECUTION BY INLAND REVENUE

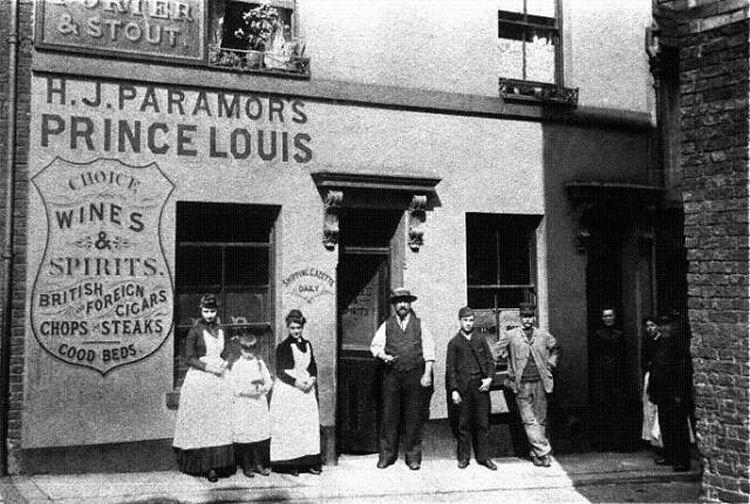

At the Police Court last Friaday, before Messrs. J. L. Bradley, F. W.

Prescott, and F. G. Wraight. Herbert George Pullen, landlord of the

“Prince Louis” public house, Chapel Lane, and A. Mangilli, restaurant

keeper, of 5, Bench Street, were charged on the information of James

Elgar, with selling on the 14th November, 1904, at 5, Bench Street,

spirits without having a license, whereby they forfeited a sum of £50.

They were further charged with selling on the 14th November, 1904, at 5,

Bench Street, beer, without having a license, whereby they forfeited a

sum of £20. They were further charged with selling a certain wine,

without a license, on the 14th November, 1904, whereby they forfeited a

sum of £20.

Mr. B. Hawkins, Solicitors' Office, Somerset House, appeared to

prosecute.

Mr. R. Mowll appeared for Mr. Pullen, and pleaded not guilty. Dr.

Hardman appeared for Mr. Mangilli, and pleaded not guilty.

Mr. Hawkins said this was a prosecution by the Commissioners of Inland

Revenue, which dealt with the question of the right of unlicensed

restaurant keepers to send out for intoxicating liquors to be consumed

by his customers. The customs was a very widespread one, and they were

not in this case seeking to say that the custom was necessarily illegal,

but in the case that he had put before them, under certain circumstances

the custom might be illegal. The informations were laid under the Excise

Acts. For spirits, section 26 6 Geo. IV. Chap. 81, the penalty for beer

under section 17 of the Act 4 and 5 Will IV. Chap. 85, and wine under

section 10 of the Act 23 and 24, Vic. Chap. 27. there were also two

other sections that he would ask their attention to. They were section

17 of 30 and 31 Vic. Chap. 19 – that section says that any person who

should receive profits from the sale of any article for which an Excise

License was required without obtaining such a license would incur the

penalty for the sale without a license. The other section, which related

to Mr. Mangilli, sectioned 26 of 6 Geo. IV. Chap. 81, provided that

where liquors were sold by an unlicensed person who was privy and

consented to the sale, he would be liable to the penalty, although not

actually the person selling. After detailing the evidence that he

subsequently called, he said that he did not think that there would be

any serious dispute as to the facts of the case, but would be rather on

the inference that the Magistrates would be asked to draw from these

facts, and on points of law. Referring to the widespread practice of any

unlicensed restaurant keeper sending out for intoxicating liquors to be

consumed by the customers at the restaurant, he referred to a case that

had been decided. Pasquire v. Neale. In that case the restaurant keeper

was charged with selling wine without a license. He was the proprietor

of a restaurant in Soho, and was a partner in a wine merchant's

business. An Inland Revenue officer went to the restaurant, and was

shown a wine list, and from this list a bottle of wine was selected. The

officer was asked for the money, and the waiter went to the licensed

premises of Mr. Pasquire, and purchased the bottle, for which he paid

apparently, but there was no evidence as to the price paid. The

Magistrates , Mr. Denman, thought there had been a sale of wine to the

officer at the unlicensed premises. The case was taken to the High

Court, but the High Court refused to reserve the decision. Of course

there was a certain amount of difference between that case and the

present one, but there was only one principle underlying all these

cases: The first question to be decided was where did the sale take

place – at the restaurant, or on the premises of the publican where the

wine was sent for? That question, he submitted, turned on the question

whether the restaurant keeper was the agent of the customer or of the

publican. If he were the agent of the publican, then the contract was

made between the customer and the publican's agent on unlicensed

premises. He submitted that Mr. Mangilli was the agent of Mr. Pullen.

There was an arrangement between the two not entered into at the request

of any particular customer, by which Mr. Pullen kept a stock of wines

for the sole purpose of being consumed by people going to the

restaurant, and for which Mr. Pullen charged a higher price then he

would to people going to his public house. In order to further the sale

of this wine, Mr. Mangilli had the wine list exposed in his restaurant

solely for the purpose of obtaining orders for these goods. He did not

expose other people's wine lists, and orders when received were at once

taken to Mr. Pullen's, and to no others, although on the way other

licensed premises were passed. He would submit that it was clear that

Mr. Mangilli and Mr. Pullen were carrying on jointly a business of

disposing at these unlicensed premises this stock of wine. That they

were jointly selling – Mr. Pullen as principle, if his statement were

true that he received the whole of the profits, and Mr. Mangilli as

agent.

James Blake Davies, in charge of the Preventative Department, said that

on the 14th of November he went to Mr. Mangilli's restaurant, 5, Bench

Street, Dover, with Mr. Cope, an officer of the Inland Revenue. He

arrived there at 7.05 p.m. and ordered dinner. Prior to entering he

posted two officers outside, Messrs. Hayward and Bate. On the table were

wine lists. The waiter serving handed him a wine list, and he ordered

Volney, price 2/6. and a 3d. Bass. The waiter asked for the money, and

he gave him half a sovereign. He gave the order at 7.17. At 7.23 the

waiter placed before him the bottle of Volney and the small Bass, and

the 7/3 change. At 7.33 he ordered two liquors of brandy and gave the

waiter a 1/-. The brandy was handed to him at 7.37 by the same waiter.

Mr. Cope drank the Bass, and witness drank a portion of the wine. Each

of them had a liqueur of brandy. When he left he was presented with the

bill (produced), which he paid.

The Magistrates Clerk: There is no reference to the drink?

Witness: No it is an ordinary bill.

On the 16th November he called upon Mr. Pullen, accompanied by Mr.

Brereton, Supervisor of the District. Witness saw Mr. Pullen there, and

he explained the object of his visit. He said, “I supply the price list

of wines,” and he handed me the one produced “to Mr. Mangilli.” It

contained the prices, the same as he sold them to Mr. Mangilli, who

received no discount, no commission, nor no return whatever. The price

list was his own making out. In the room where they were conversing he

saw a number of baskets of wine, which were numbered, the numbers

corresponding with the numbers on the list. He then said, “I should not

keep the stock of wine I do if not for Mr. Mangilli, as my trade is not

a wine trade. I had the wine lists printed and I supply these lists to

Mr. Mangilli.” Witness asked him to produce the book in which the

transactions with Mangilli and himself were recorded. He said he had no

book. Witness told him he knew there was a book. He then said,

“Mangilli's brings a book here when he makes purchases. Either I or my

wife make the entries in the book. In this book I enter the number or

the description of the wine, and the amount as shown in my price list.”

Witness asked him whether he took the trouble to keep a book like that

if all the money were paid in respect to each sale. He replied that the

book was kept so far that there should be no dispute as to what was

paid. Witness said, “Why does Mangilli keep the book?” He replied, “So

that there cannot be an overcharge.” He said that arrangement had

started last summer. Pullen said, “Mangilli used to go elsewhere, but I

did not think it fair to be made a convenience of on Sundays and Bank

Holidays when other spirit merchants were shut.” Mangilli said he could

not see why he should not. Witness put it that Mangilli's man passed

Lukey's. Pullen said “If he went to Lukey's he did not think he should

serve him or keep a stock of wine.” He said he had no call for wine as

very few of his customers ever asked for it. Witness then went to Mr.

Mangilli's at 5, Bench Street. He found Mr. Cope with Mr. Mangilli. Mr.

Cope handed him a book in which sales were recorded. This was the book

produced. The orders which witness gave were recorded in the book – the

Volney 2/6, brandy 1/-, and the small Bass. Witness asked My. Mangilli

when he made the arrangement with Pullen, and he said he could not

remember. Witness asked him if he gave the whole of his custom to Mr.

Pullen in consideration of Mr. Pullen serving him on Sundays and Bank

Holidays. He said, “I cannot remember.”

Dr. Hardman objected to the way the evidence was being taken. The

suggestions were all contained in the questions, and not in the answers.

The Magistrates Clerk said they would put it down as an answer to

further questions.

Dr. hardman: That is not the proper way; the evidence should be. “I

asked so and so, and he answered “So and so.” This is a three-hours'

cross-examination, or rather badgering.

The Witness: No, it was not; you were not there.

Witness asked him if he or his waiter kept a book. He said he did not

keep a book, nor did the waiter. He said the book (produced) was Mr.

Pullen's book. Witness asked who supplied the wine list, and he said Mr.

Pullen. Witness asked him who selected the wines, and he said Mr. Pullen

selected them, that being his business. He asked him who made the ticks

in the book, and he said he could not say. He said, “My people do not

touch the book.” Witness said he noticed a bottle of Johnny Walker

written there and Mangilli said that was for his own use. The waiter, in

going to Mr. Pullen's, would pass by Messrs. Lukey's wine merchants,

premises. Binfield's was close behind Pullen's premises. The

“Shakespeare” and the “Guildhall” were also close. Witness had read the

prices charged and the price list produced.

Mr. Mowll objected to witness being asked how these compared with

ordinary wine lists. Witness said he considered the bottle of Volney for

which he was charged 2/6 would have been dear at 1/-.

Cross-examined by Dr. Hardman. Witness produced his notes which he made

at Mr. Pullen's during his conversation with him. He went to Mr.

Pullen's at about 11, but the conversation with him and Mr. Mangilli did

not last till 2, as he had lunch at Mr. Mangilli's. The note was a

substantial record of what occurred.

Dr. Hardman: That is to say you took what you thought was in your

favour?

Witness: I took what he stated exactly.

Let us test it. You said that Mr. Mangilli said his book was at

Pullen's. I wonder whether you have got that? – You look and see.

I have and see you have not got that – I put several questions I did not

put down, and a portion of the conversation given today was given from

memory.

When you went in you said that you were handed a list. Do you suggest

that you did not call fro a wine list?

Yes. I saw a wine list on the table.

Did you not ask the waiter for a wine list?

Yes, to hand me the list on the table.

And you consider it a fair way of stating that the waiter handed you a

wine list when you asked the waiter for a wine list?

The wine list was a little out of my reach.

It does not matter whether it was or not, you asked them for the wine

list?

It saved me getting up and taking it.

Do you think it would be more accurate if you gave it as it took place?

I think my answer is quite consistent as recorded.

It is now; it is consistent with the truth?

And it was.

Dr. Hardman asked if the course pursued in getting the wine was not the

usual one?

Mr. Hawkins said the witness was not entitled to give his opinion.

Dr. Hardman: This gentleman is an expert.

Mr. Hawkins: Not on question of law, that is the whole point of the

case.

Witness in answer to further questions by Dr. Hardman said that he

repeatedly asked Pullen if he did not get some advantage from the sale

of wine at the restaurant, and he stated that the list contained the

price of wines as he sold then to Mangilli, and that Mangilli had no

discount.

Did it not occur to you that it was a reasonable thing in order to

secure the beer and spirit trade that Mr. Pullen might put himself to

some little inconvenience about he wines?

It struck me as unreasonable, and to be in accordance with other similar

cases that we have.

Dr. Hardman then proceeded to ask witness questions in reference to the

book, and the witness declared that Pullen told him that there was no

book.

Mr. Mowll pointed out that the answer in witness's own notes was that

Pullen said he had no book, which was a very different thing.

Witness continuing said that Mr. Pullen gave him a reason for keeping

the book, but he did not believe it.

Now with reference to what you call the arrangement. Mr. Pullen clearly

explained to you how that came about?

Yes.

He explained to you that Mr. Mangilli sent to different places, and that

he was anxious to secure the custom, and that the shops closed early on

Wednesdays and on Sundays?

Yes.

Do you know that Lukey's or Binfield's cannot sell 6d. of brandy or

liquors?

Yes, but he could get it from the “Shakespeare.”

And therefore Pullen was anxious that Mangilli should not make a

convenience of him on Sundays, but should give him the other trade.

He said that the arrangement was come to in consideration of his

supplying on Sundays and Bank Holidays, and that he was to get the whole

of his custom right through, as he put it.

Witness, in reply to further questions, said that he could not say that

the “Prince Louis” was the closest licensed house. He did not subject

Mr. Mangilli to a cross examination of more than half an hour. He began

to cross examine Mr. Mangilli about the arrangement after Mr. Cope

finished. Mr. Mangilli's Italian origin was no difficulty to him. He

understood English perfectly, and was well acquainted with the law. The

reply “I cannot remember” was what they usually got from the Italians.

Witness on being pressed, admitted that Mr. Mangilli answered a great

many questions other than by saying, “I do not remember.” He first said

when witness asked him whether he had any discount or commission “I

cannot remember,” but he said after, “None whatever.”

Dr. Hardman: This is the first time you have admitted this. Do you call

that a fair way of giving evidence?

Witness, in reply to further questions said that he did not tell

Mangilli that he was certain there was a secret arrangement as they were

not fools; he would not have used the latter expression, although he

might have said there was a secret arrangement. The conversation took

place upstairs. Mangilli did not tell him that he used to deal at the

“Shakespeare” but had ceased for certain reasons. Whilst they were

conversing with Mr. Mangilli Mr. Cope went to Mr. Pullen's, but he

certainly never authorised him to say, “Look here, if you give Mr.

Mangilli away we will not prosecute you,” and to tell Mr. Pullen what he

should say.

Cross-examined by Mr. Mowll: Witness said that he considered he

purchased the wine, etc., off Pullen according to the wine list.

Alfred William Cope, officer in the Inland Revenue Prevention Staff,

said that on the 14th November he accompanied Mr. Davies to Mangilli's

and corroborated his statement as to the meal. He was at Mangill's

premises on the 16th November. He corroborated Mr. Davies's statement as

to what took place between Mr. Davies and Mangilli. He went to Pullen's

from Mangilli's, and returned afterwards. He denied that he said to

Pullen that he would not be prosecuted if he gave Mangilli away. He

asked witness what he could do, and he advised him to see a solicitor.

Previously, on the 16th, he had a conversation with Mangilli, and told

him that he knew he had a book in which entries were made relating to

the supply of wines from the “Prince Louis.” Witness looked round and

saw the book (produced) on a shelf behind the bar. Mr. Mangilli at first

refused to get it but on witness stepping to get it, showed it to him.

He told Mangilli that Mr. Davies was at Pullen's. he said that he had a

wine license for his business at Deal. Witness said, “Do you get a

profit for commission from Pullen?” and after grinning he replied, “I

can't say.” He continued to grin all the time he was there. Witness

asked him again, and he said he could not say. Witness then said, “You

used to deal at the “Shakespeare;” are the prices you charge now similar

to those you charged then?” and he said, “Yes.” Witness said, “Do you

pay more now than when you dealt at the Shakespeare?” he said he could

not say. Witness said, “When you dealt at the “Shakespeare” did you

charge more than you paid?” he said he could not remember. Witness asked

him if the wine was of the same quality as it was before, and he said,

“Yes, about the same.” Witness asked, “If you charge the same as you pay

for the wine, why do you pay 50 per cent more than you need to?” he said

he could not say. Witness said, “Whose book is this?” and he said he did

not know, ask Pullen; he said he did not make the ticks in the book.

Cross-examined by Dr. Hardman: It was after three quarters of an hour of

this sort of thing that Mr. Davies took up the running?

I think it was half an hour.

I suppose Mr. Mangilli thought these were peculiarly English methods and

as an Italian he was a little out of it. They were singularly English

methods of dealing with a man?

I thought there was nothing in it.

I am glad you think that it was perfectly right and proper that a

foreigner should be badgered in this way and that every method should be

tried to convict him out of his own mouth?

Foreigner! He knows more than I do. I saw the sort of man he was.

What sort?

He was smiling all over his face, and saying, “I do not know.” I never

met a man like him before. (Laughter.)

Then it was quite a new experience, and you did your best for him?

I reported what took place.

Witness continuing, said, in reply to further questions, that Mr. Davies

when he came into Mr. Mangilli's read over what Mr. Pullen had said.

Witness then went to Mr. Pullen's and told him the substance of what Mr.

Mangilli had said. He made no statement to Pullen about not being

prosecuted. He could not have done such a thing. He pointed out to Mr.

Pullen that he had a great deal to lose, and Mr. Mangilli very much to

lose.

Cross-examined by Mr. Mowll. Witness said he went to the “Prince Louis”

thinking there was an understanding between Pullen and Mangilli, and he

went there to find out. Witness told Pullen he had a lot to lose, and

Mangilli very little. Witness did not ask Pullen to tell him his “little

game.” Witness did not say to him that one of them had got to go through

with it.

Mr. Mowll told the witness that Mr. Pullen came to him the same

afternoon and gave him the account of the conversation that he was

putting to him.

Witness in reply to further questions, admitted that he said to Pullen,

“You don't think that Mangilli is such a fool as to let you have this

for nothing,” and Pullen replied that Mangilli got nothing.

Mr. Mowll: You see how this witness admits all the questions I put to

him.

Mr. Hawkins: Yes, except the important ones.

Mr. Mowll: Except the one he was warned of.

Did you finish up by saying “As you will not tell me I will summon you

both?

No, I did not. If you do not mind I might say that I finished up with,

“I have heard Mr. Mowll is a very good man.” (Laughter.)

Mr. Mowll: That is a most happy remark, to which I have not the

slightest objection. (Laughter.)

By Mr. Hawkins: he never made the slightest attempt to induce Mr. Pullen

to make a statement by any threats? He pointed out to him one brand of

champagne, of which the ordinary price was 8/-. and for which he was

charged 12/- at Mr. Mangilli's.

The Magistrates' Clerk: That is no offence.

James John Hayward, officer of the Inland Revenue, said: On the 14th

November he saw Mr. Davies and Mr. Cope go into Mangilli's premises. He

remained on observation. At 7.16 a waiter came out of the Restaurant and

went to the “Prince Louis” public house. Witness followed him, and he

ordered a small bottle of Volney and a small Bass. He placed the book

(produced) on the counter and half a sovereign, and said, “I'll call

back in a minute.” The lady behind the bar took the book and wrote

something in it, but he did not know what it was. She placed the bottle

of Volney and Bass on the counter, together with the book and 7/3. The

waiter returned and took them to Mangilli's. That was at 7.22. While he

was away from the Restaurant, he left Mr. Bate outside.

Percy Hart Bate said that on the 14th November he was on observation

outside Mangilli's. At 7.34 a waiter came from the Restaurant with a

book and footed tumbler in his hand. He went into the “Prince Louis”

public house and called for two liqueurs of brandy. A lady behind the

bar served him and took the book, and witness saw her put 1/- in the £

s. d. column. The waiter put down 1/- and received no change. He took

the brandy in the tumbler back to the restaurant at 7.36.

George Edgar, Inland Revenue Officer for Dover, said that Mangilli had

no license for the sale of intoxicating liquors to be consumed either on

or off the premises. He was licensed as a Restaurant keeper, and a

tobacco dealer. Pullen was a fully licensed on and off dealer at the

“Prince Louis.”

Mr. Mowll submitted on behalf of Mr. Pullen that there was no evidence

of any offence by him. They had it in evidence that the wines and

spirits were sold at the “Prince Louis,” for which he was fully

licensed. The only possible ground for suggesting that he sold them at

5, Bench Street was the fact that there was a wine list at Mangilli's,

but it was stated on it that the wines on it were specially selected by

H. G. Pullen, “Prince Louis,” Chapel Lane. There could be no reasonable

doubt, therefore, that the wines were going to be supplied from the

“Prince Louis.” Referring to the case of Pasquire and Neale, he pointed

out that the Restaurant keeper had a partnership in a wine business

close by, and it was held that he sent his waiters to purchase his own

wine, and the Lord Chief Justice pointed out that whilst if the wine

were sent for from a neighbouring house the sale would not take place at

the unlicensed premises of the Restaurant, but that in the Pasquire case

he was employing his waiter as an agent to promote the sale of his own

wines. It was a very different case from this case, because there was no

evidence of any interest whatever, notwithstanding the very long

cross-examination his clients had been subjected to. In Pasquires case

there was no evidence of the amount that was paid, but there was in

this. As to the place where the sale took place, he pointed out that

when the waiter was given the bottles and paid for them at Pullen's they

were then the waiter's property, and how could it be said that a sale

under these circumstances took place at Mangilli's Restaurant. He quoted

three cases where beer was sold by agents at a house and the money

received at the house by an agent of the brewer, and in those it was

held that the contract was not accepted till it reached the brewer. So

in this case he contended there was no account at all till it was

accepted by Pullen at his premises. He also pointed out that Pullen's

case was strengthened by the fact that the transmitter of the order was

not even in his employ. The wine list was nothing more than an

advertisement of what customers who want to get stuff from Pullen's at

Mangilli's can obtain by sending the waiters there.

Dr. Hardman also submitted there was no case against his client. The

only case on which the prosecution relied was one where the case was

decided purely on the ground that the Restaurants keeper was a part

owner in the wine business, which, as had been pointed out, did not

apply to the present case. The cases that had been quoted by Mr. Mowll

were summonses in which the principle was laid down that the sale takes

place where the goods are appropriated to the contract. That was where

the bottles were separated from the other bottles and placed to the

customer's credit or handed to his messenger. He objected to the way the

evidence had been given by Mr. Davies in saying that the waiter handed

him the wine list, when he asked him for it. As to their suggestions and

surmises, the case was built on them. What was proved to be done was

absolutely legal, but they said it cannot be right. “These people are

not fools, there must be a secret arrangement. We have no evidence of

it, but we ask the Court out of their inner consciences and anything but

the evidence to say there was an arrangement.” Why should the Court find

that? The effects of a conviction were terrifying. No person so

convicted could hold a license, and if he held one it was immediately

forfeited, and was unable for the rest of his life to hold a license. It

was, therefore, therefore, essential that the offence should be

strongly, fully and convictingly proved.

At the conclusion of Dr. Hardman's speech he accused the prosecuting

witnesses of attempts to exaggerate or misunderstand, and a sharp

passing of words took place between Dr. Hardman and Mr. Hawkins, the

former sticking to his charge, although he said he did not include Mr.

Hawkins.

Mr. Hawkins, referring to the hardship which Dr. Hardman had referred to

in the forfeiture of the license, said that was only carried on the

conviction on the charge of selling spirits without a license, and he

would withdraw that summons. His contention of the question of law was

that Mr. Mangilli was Mr. Pullen's agent, on the ground that the money

in the first instance was handed over in Mr. Mangilli's premises, and

that the appropriation of the goods took place there.

Dr. Hardman said that if that were so no restaurant keeper could send

out for anything.

The Bench said: The bench are unanimous that the case must go on and be

heard. You say there is no case, but we consider there is without any

question whatever.

Herbert George Pullen, licensee at the “Prince Louis” public house, who

said he had held the license for three years. The house was within about

thirty yards from Mangilli's Restaurant. From time to time he had

supplied wines, spirits and beer to Mangilli, to men bearing the

appearance of waiters from Mangilli. Mangilli was not obliged to come to

him. The book which had been produced contained entries made by the wife

or himself. Items were put in it of the goods supplied to Mangilli.

Cross-examined by Mr. Hawkins. He had known Mangilli for many years.

Mangilli had dealt with him a long time. About April he asked Mangilli

if he kept all the wines that Mangilli required, would he deal off him.

He did not ask him to deal exclusively off him. Mangilli asked him to

get the wine list printed, and witness paid for it. He copied the list

from Mr. Binfield's list. The prices on witness's list corresponded with

Mr. Binfield's. After April he got in the special stock of wine, but

anyone who liked could buy them. No discount or commission was allowed

by him to Mangilli. He got the wine from Mr. Binfield. Mangilli

suggested having a book. He was handed one of Mr. Binfield's retail

price lists, but witness said he had not seen it before. The prices did

not correspond with the list he supplied at Mr. Mangilli's.

Mr. Mowll pointed out that the charges Mr. Binfield made were exactly

the same as those witness did.

Witness in reply to further questions, said he did not know the price

that Mr. Binfield charged private customers. He got his goods from him

at wholesale price. He did not know whether Mr. Mangilli sent elsewhere,

but had seen his waiters coming out of other public houses with jugs or

bottles. The book was simply kept to see that there was no over charge.

Cross-examined by Mr. Mowll. He had been advised by Mr. Mowll that what

he was doing was quite legal.

Achille Mangilli said that he carried on business at 5, Bench Street for

4½ years, and during that time had sent out to most of the neighbouring

houses for wines, spirits or beer that customers asked to be supplied

with. Up to two years ago he was in the habit of taking a certain share

in the profits, but was then advised by an Excise Officer that it was

illegal. He had, however, never had any such arrangement with Mr.

Pullen. During the past two years he had never received any commission,

discount or return. He had some time since applied for a license for his

premises, and he was then advised to keep a book showing what business

he did, so that he could be seen by the Bench. He had kept the book

since, and had also found it useful in checking his waiters, and had by

its means discovered cases of dishonesty on two or three occasions. He

was under no obligation to go to Mr. Pullen. But a wine and spirit

merchant was unable to supply him after eight in the evening and on

Wednesday afternoon and Sundays. He kept open till eleven in the

evening, and a great deal of business was done after eight, and it was a

great convenience for Mr. Pullen to be able to supply him. He had when

asked for a special wine sent for it to wherever requested. Whatever

profit Mr. Pullen made on the sales to witness's customers he had not

benefited directly or indirectly. Referring to the conversation with Mr.

Cope and Mr. Davies, witness denied that he said, “I cannot remember.”

He had answered their questions, but when they kept badgering him he

began to get angry and said, “I can't remember.”

Cross-examined. He had never had more than one person's wine list on his

premises at the same time. He had one from the “Shakespeare,” and he

also had one from Mr. Binfield's. he found that owing to the hours of

business it was more convenient to obtain the wines, etc., through Mr.

Pullen. Mr. Binfield gave him 15 per cent commission up to the time he

was warned by the Excise Officer. He then told Mr. Binfield that he

could not take it as it would be dangerous, and he did not take it

afterwards. He continued to deal with Mr. Binfield, and the prices,

which were exactly the same as Pullen's, were continued to be charged.

Mr. Mowll offered to recall Mr. Pullen to give evidence as to the ticks

in the book to which Mr. Mangilli was subjected to cross-examination,

but Mr. Hawkins said he did not want him.

Mr. Mowll and Dr. Hardman both shortly addressed the Bench for the

defendants, and Mr. Hawkins again extended his offer to withdraw the

summons in respect to the spirit license if the bench saw fit.

The Magistrates retired, and after a quarter of an hours consideration,

returned and the Chairman said: I think the gentlemen on both sides will

say we have given the case very ample consideration. It was a very

serious case, and we have come to the conclusion that we do not consider

the evidence sufficient to convict.

|