|

The Harbour

Folkestone

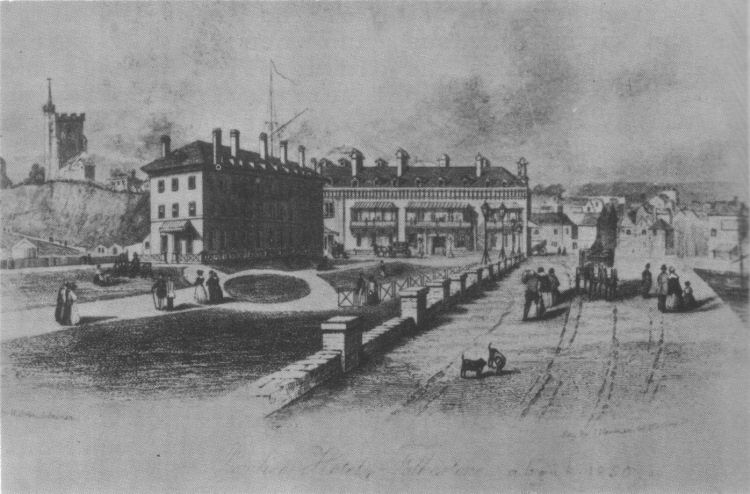

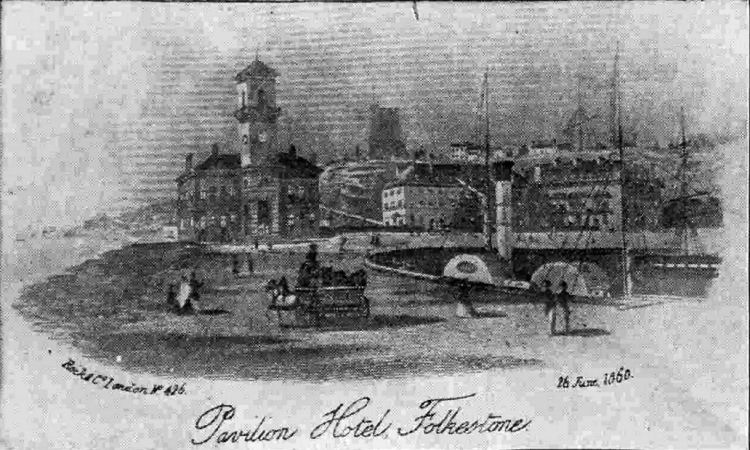

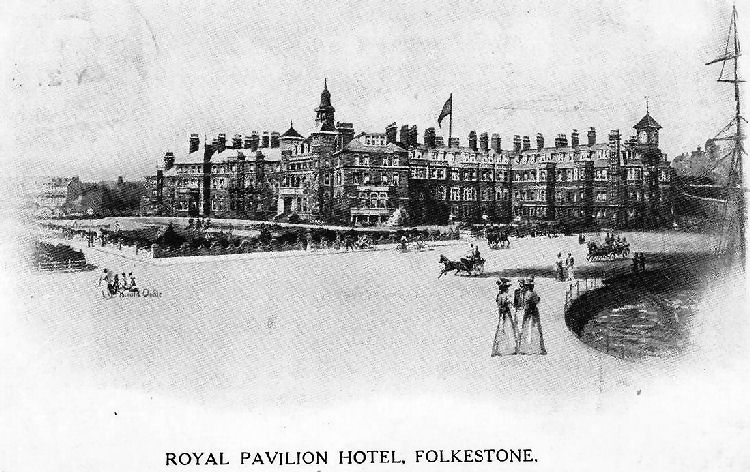

Pavilion Hotel circa 1850. |

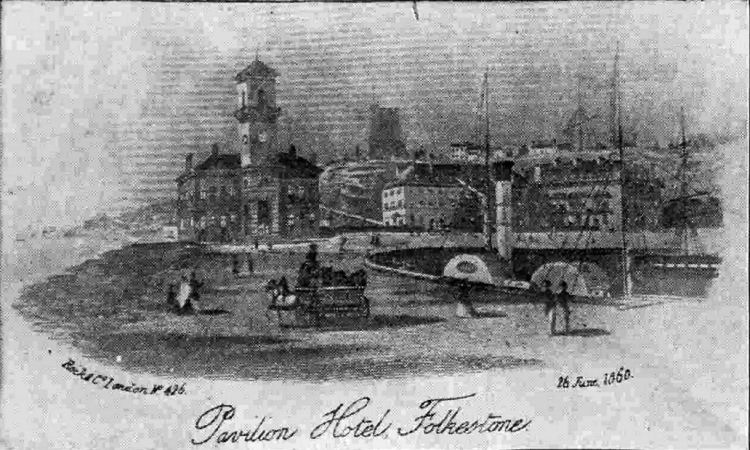

Above print dated 20th June, 1860 also showing the Tidal Packet Boat in

the Inner Harbour and the old Custom-house. |

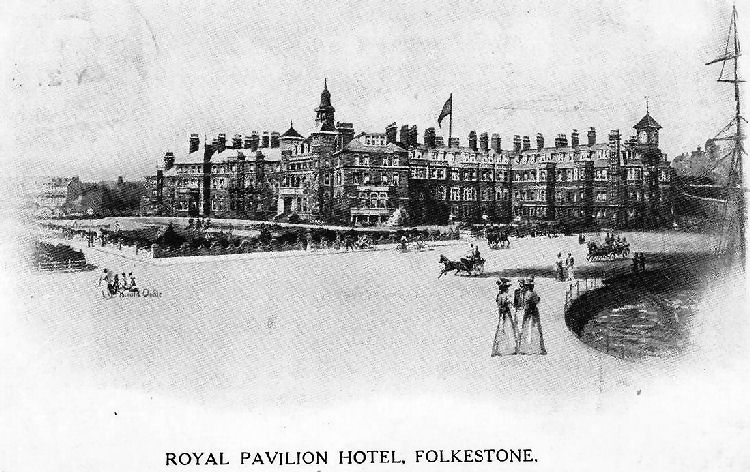

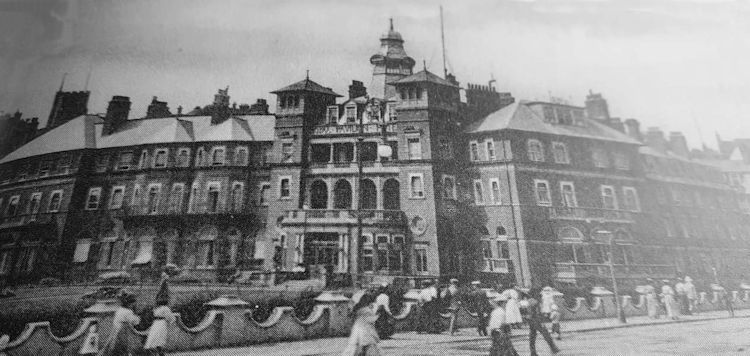

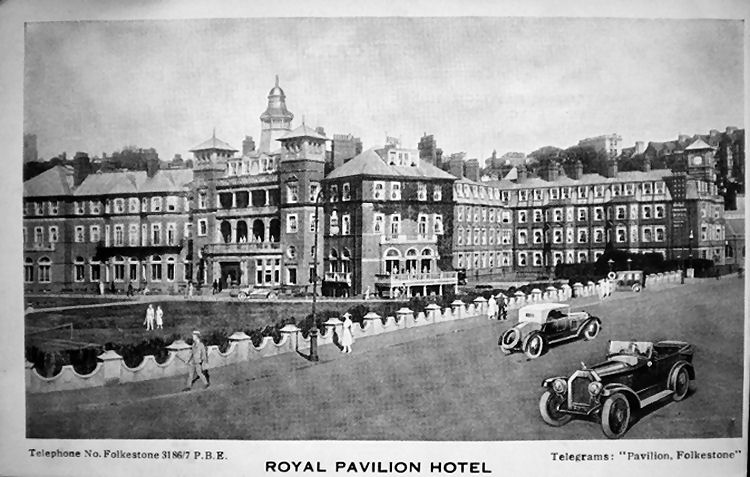

Above postcard, circa 1903, kindly sent by Rory Kehoe. Panoramic view,

which also takes in (from L to R) the "Royal

Pavilion Hotel," the "Princess

Royal Hotel" (in the livery of Nalder & Collyer's Croydon Brewery)

the "London and Paris Hotel"

and just visible behind the ships, the upper part of the "Alexandra

Hotel." |

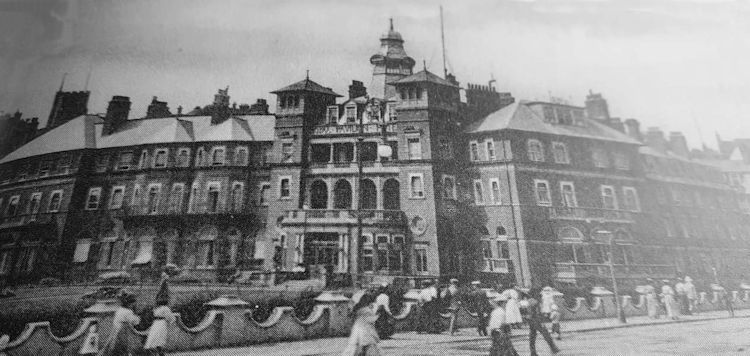

Above postcard, date 1911, kindly sent by Mark Jennings. |

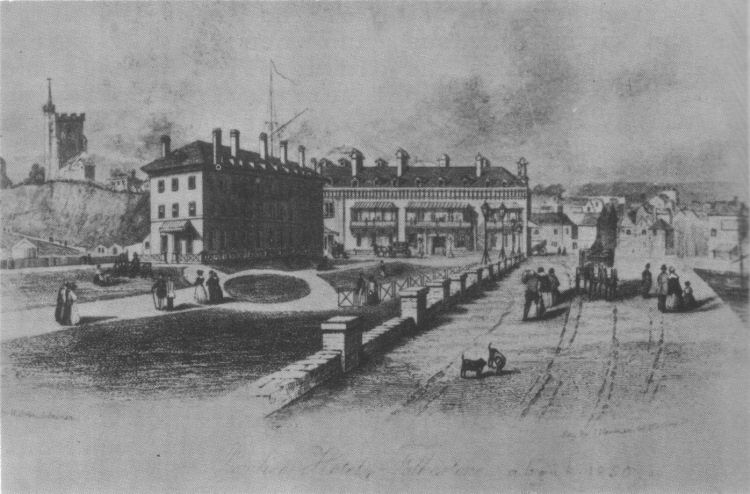

Above print from the book "Dickensian Inns and Taverns, 1922." |

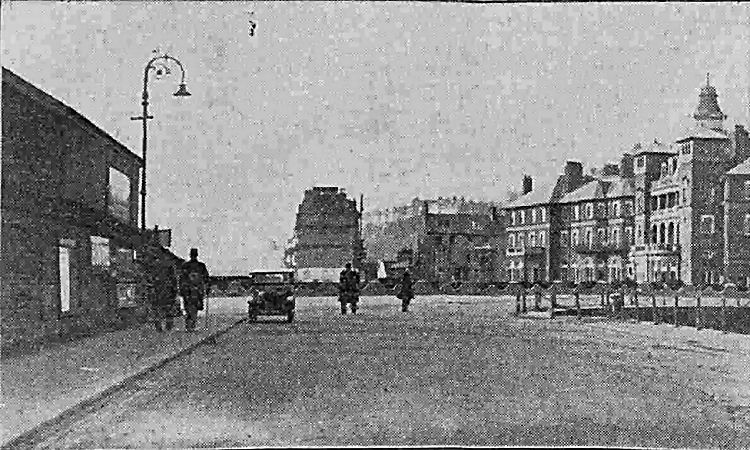

Above postcard undated. |

Above postcard, date unknown. |

Above photo, date unknown. |

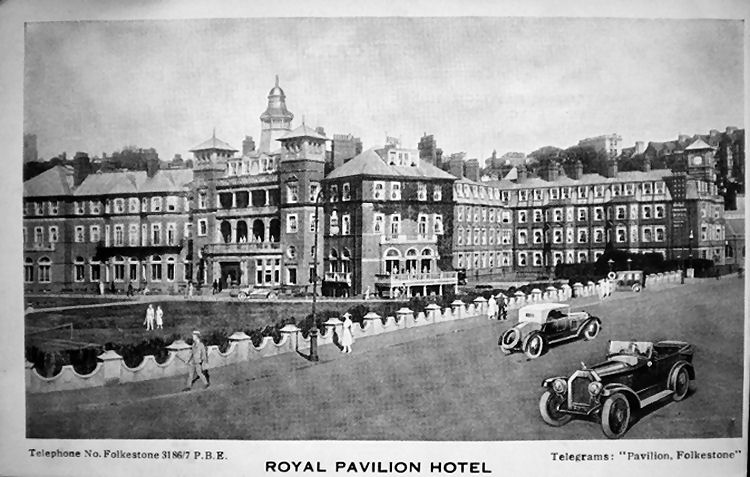

Royal Pavilion Hotel date unknown. |

Above photo, 1933. |

It appears that the new building with this name replaced another earlier

one with the same name that was being demolished in 1844.

Kelly's directory of 1899 says the following:- "The Royal Pavilion Hotel"

which faces the sea in a sheltered position, has an extensive Winter garden,

and is close to the steamboat and promenade piers and the Undercliffe.

Kelly's 1934 stated that it was adjacent to the landing stage. Bedrooms

fitted with heating, hot and cold water. Garage. Telegrams, "Pavilion,

Folkestone;" Telephone: Folkestone 3186.

|

Kent Herald 3 August 1843

The South Eastern Railway Fete

The mayor and corporation of Folkestone, and the directors of the Dover and

South Eastern Railway Company, on Tuesday, celebrated the opening of the

communication by regular steam-packets between the ports of Folkestone and

Boulogne by a public breakfast and other festivities at the "South Eastern

Pavilion Tavern" at Folkestone. The town was filled all day long with visitors

from the adjacent places, and by arrivals from London, to be present at the

celebration. The vessels in the harbour, which has been purchased by the railway

company, and which it is in contemplation to enlarge and improve forthwith, were

decorated with flags and ensigns, and presented a very gay appearance. At

half-past 12 o’clock the City of Boulogne steamer came into the harbour and

landed the mayor and authorities of Boulogne, and the gentlemen of that place.

Their arrival was announced by a salute of ordnance, and they were received on

landing by the mayor (Mr. Major) and corporation of Folkestone and conducted to

the terminus of the railway, where they inspected the engines, carriages, &c,

and expressed their satisfaction with the arrangements. About this time the down

train from London came in, having brought down several of the directors and many

more guests to the breakfast. In the earlier part of the day the Sir William

Wallace, one of the eight vessels intended to make the passage between Boulogne

and Folkestone, had arrived from London, and taken from Folkestone to Boulogne

in this her first trip upwards of 100 passengers, and another vessel shortly

afterwards came in from Boulogne with a large number of passengers. It appears

that the harbour of Folkestone in its present state contains at high tide water

to the depth of 20 feet, and that when the wind is south or south-west it

affords a better entrance for vessels than Dover. By 4 o’clock the town was

filled with people, and the two moyors, and those by whom they were attended,

the directors and visitors having returned from the railroad, the breakfast

commenced. In order to afford accommodation to the very numerous party

assembled, and to the various groups collected together, an elegant marquee,

sent down for the occasion from the manufactory of Mr. B. Edgington, of Duke

Street, Borough, had been erected in front of the Pavilion Tavern facing the

sea, and beneath this were placed seats and tables; and in addition to this a

building, formerly a boat-house, had been converted into a banqueting room, and

fitted up with great taste by Mr. Vantini, the proprietor of the tavern, to whom

it is but justice to say that his arrangements for the gratification of his

guests were most satisfactory. The repast, to which nearly 200 persons sat down

at 4 o’clock was in a very excellent style.

The chair was taken by the mayor of Folkestone, supported on his right hand by

Mr. Baxendale, and on his left by M. Adam, the mayor of Boulogne. There were

also present. Mr. Marjoribanks, M.P. for Folkestone, M, Bailley, commandant of

the artillery at Boulogne. M. De la Sabloniere, Lieut. Col. Of the National

Guard of that city, M. De Mentque, sub-prefect, M. Sauson, Colonel of the

National Guard, Captain Tyndall, M. Marquet, civil engineer of Boulogne, M. Le

Compte, Grand Vicaire, Mr. Cardwell, M.P., Mr. Hamilton, Consul of Her Britannic

Majesty, Baron de Chivenet, Commandant of the garrison at Boulogne, M. De

Hastingham, King’s Advocate at Boulogne, M. Desaux, Captain Barthelemy, Mr. F.

Cubitt, Captain Charlwood, R.N., Captain Peat, R.N., General Hodgson, M. De la

Porte &c., the directors of the railway, &c. The company, in addition to the

good things placed on the tables, were entertained by a musical band from

Boulogne, which during the breakfast played some of the national airs of England

and France.

The mayor of Boulogne gave the first toast, viz., “the health of her Majesty

Queen Victoria" which was drunk with the usual honours. The mayor of Folkestone

then proposed “the health of his Majesty Louis Philippe," which was also

received with cheers, and drunk with all the honours. The next toast, “the Royal

Families of England and France," was the third in succession, and was drunk with

the honours, after which the health of “the Mayor of Folkestone," was proposed

and drunk, and the mayor returned thanks. On the health of “the Mayor of

Boulogne" being drunk, which came next in succession, M. Adam, in returning

thanks, detailed the history of the projected railroad from Paris to Boulogne

through the French Chambers, and observed that the recent fete given at Boulogne

on occasion of the railroad and steamboat excursion from London to that city had

had a beneficial effect in showing what could be done by railroads and steamers,

and had expedited the wished-for proceedings. M. Adam repudiated all intention

of injuring Calais by supporting a communication between Boulogne and

Folkestone, and said there was sufficient traffic for both ports, and enough to

render the competition of the one no injury to the other.

On the health of Mr. Baxendale and the Directors of the South Eastern Railroad

being drunk, that gentleman returned thanks, and in doing so described the state

of Folkestone harbour from the printed report and memorial laid before the

commissioners of Her Majesty's treasury by the merchants, shipowners, and

masters of ships of the port of London. Mr. Baxendale said he considered the

interests of the four ports of Boulogne, Calais, Dover, and Folkestone, would

all be advanced by the more rapid communication of railroads, and that it was

not from the injury of any one of them that the others should receive increased

advantages. He then briefly adverted to the state of the harbour of Folkestone

before it was purchased by the railroad company; and pointed out the

capabilities it possessed, and the improvement of which it was susceptible. He

hoped the example set to the government of the country by the company would lie

productive of good effects in calling their attention to what might be done to

render other harbours better than they now were. Mr. Baxendale concluded amidst

loud cheering.

The healths of Mr. Marjoribanks, Mr. Bleaden, and several other gentlemen were

then drunk, and those gentlemen returned thanks. After which a large portion of

the company retired in order to return by the train. The festivities were,

however, not over till a late hour, and it was nearly midnight before the

steamer conveyed the French guests back to Boulogne.

|

|

Dover Telegraph 5 August 1843.

The South Eastern Railway Fete.

The mayor and corporation of Folkestone, and the directors of the

Dover and South Eastern Railway Company, on Tuesday, celebrated the

opening of the communication by regular steam-packets between the

ports of Folkestone and Boulogne by a public breakfast and other

festivities at the South Eastern Pavilion Tavern at Folkestone. The

town was filled all day long with visitors from the adjacent places,

and by arrivals from London, to be present at the celebration. The

vessels in the harbour were decorated with flags and presented a

very gay appearance. At half-past tweIve o'clock the City of

Boulogne steamer came into the harbour and landed the mayor and

authorities of Boulogne, and the gentlemen of that place. Their

arrival was announced by a salute fired by the galvanic batteries,

and they were received on landing by the mayor (Mr. Major) and

corporation of Folkestone and conducted to the terminus of the

railway, where they inspected the engines, carriages, &c, and

expressed their satisfaction with the arrangements. About this time

the down train from London came in, having brought down several of

the directors and many more guests to the breakfast. They then

proceeded to take an experimental trip per rail to Ashford and back.

Upon their return, about 4 o'clock, the breakfast commenced, to

which about 200 persons sat down.

The chair was taken by the mayor of Folkestone, supported on his

right hand by Mr. Baxendale, and on his left by M. Adam, the mayor

of Boulogne. There were also present. Mr. Marjoribanks, M.P. for

Folkestone, the authorities and various gentlemen from Boulogne, Mr.

F. Cubitt, Captain Charlwood, R.N., Captain Peat, R.N., General

Hodgson, the directors of the railway, &c., &c.

The mayor of Boulogne gave the first toast, viz., “the health of her

Majesty Queen Victoria" which was drunk with the usual honours. The

mayor of Folkestone then proposed “the health of his Majesty Louis

Philippe," which was also received with cheers, and drunk with all

the honours. The next toast, “the Royal Families of England and

France," was the third in succession, and was drunk with the

honours, after which the health of “the Mayor of Folkestone," was

proposed and drunk, and the mayor returned thanks. On the health of

“the Mayor of Boulogne" being drunk, which came next in succession,

M. Adam, in returning thanks, repudiated all intention of injuring

Calais by supporting a communication between Boulogne and

Folkestone, and said there was sufficient traffic for both ports,

and enough to render the competition of the one no injury to the

other.

On the health of Mr. Baxendale and the Directors of the South

Eastern Railroad being drunk, that gentleman returned thanks, and in

doing so described the state of Folkestone harbour from the printed

report and memorial laid before the commissioners of Her Majesty's

treasury by the merchants, shipowners, and masters of ships of the

port of London. Mr. Baxendale said he considered the interests of

the four ports of Boulogne, Calais, Dover, and Folkestone, would all

be advanced by the more rapid communication of railroads, and that

it was not from the injury of any one of them that the others should

receive increased advantages. He then briefly adverted to the state

of the harbour of Folkestone before it was purchased by the railroad

company; and pointed out the capabilities it possessed, and the

improvement of which it was susceptible. He hoped the example set to

the government of the country by the company would lie productive of

good effects in calling their attention to what might be done to

render other harbours better than they now were. Mr. Baxendale

concluded amidst loud cheering.

The healths of Mr. Marjoribanks, Mr. Bleaden, and several others

were then drunk, and those gentlemen returned thanks. After which a

large portion of the company retired in order to return to London by

the train. The festivities were, however, not over till a late hour,

and it was nearly midnight before the steamer conveyed the French

guests back to Boulogne.

|

|

West Kent Guardian 5 August 1843.

The mayor and corporation of Folkestone, and the directors of the

Dover and South Eastern Railway Company, on Tuesday, celebrated the

opening of the communication by regular steam-packets between the

ports of Folkestone and Boulogne by a public breakfast and other

festivities at the South Eastern Pavilion Tavern at Folkestone. The

town was filled all day long with visitors from the adjacent places,

and by arrivals from London, to be present at the celebration. The

vessels in the harbour, which has been purchased by the railway

company, and which it is in contemplation to enlarge and improve

forthwith, were decorated with flags and ensigns, and presented a

very gay appearance, whilst from the old tower of the church the

bells rang forth a merry peal. At half-past 12 o'clock the City of

Boulogne steamer came into the harbour and landed the mayor and

authorities of Boulogne, and the gentlemen of that place invited to

be present at the festival. Their arrival was announced by a salute

of ordnance, and they were received on landing by the mayor and

corporation of Folkestone and conducted to the terminus of the

railway, where they inspected the engines, carriages, &c, and

expressed their satisfaction with the arrangements. About this time

the down train from London came in, having brought down several of

the directors and many more guests to the breakfast. In the earlier

part of the day the Sir William Wallace steamer, one of the eight

new vessels intended to make the passage between Boulogne and

Folkestone, had arrived from London, and taken from Folkestone to

Boulogne in this her first trip upwards of 100 passengers, and

another vessel shortly afterward came in from Boulogne with a large

number of passengers. It appears that the harbour of Folkestone in

its present state contains at high tide water to the depth of 20

feet, and that when the wind is south or south-west it affords a

better entrance for vessels than Dover.

By 4 o'clock the town was filled with people, and the two mayors,

and those by whom they were attended, the directors and the visitors

having returned from the railroad, the breakfast commenced. In order

to afford accommodation to the very numerous party assembled, and to

the various groups collected together, an elegant marquee, sent down

for the occasion from the manufactory of Mr. B. Edgington, of Duke

Street, Borough, had been erected in front of the Pavilion Tavern,

facing the sea, and beneath this were placed seats and tables; and

in addition to this a building, formerly a beat house, had been

converted into a banqueting room, and fitted up with great taste by

Mr. Vantini, the proprietor of the Tavern, to whom it is but justice

to say that his arrangements for the gratification of his guests

were most satisfactory. The repast, to which nearly 200 persons sat

down at 4 o'clock, was in a very excellent style. The chair was

taken by the mayor of Folkestone, supported on his right hand by Mr.

Baxendale, and on his left by M. Adam, the mayor of Boulogne. There

were also present Mr. Marjoribanks, M.P. for Folkestone; M. Bailly,

commandant of the artillery ait Boulogne; M. De là Sabloniere,

lieutenant colonel of the national guard of that city; M. De

Mentque, sub-prefect; M. Sanson, colonel of the national guard;

Capt. Tyndall, M. Marquet, civil engineer at Boulogne; M. Le Comte,

grand vicaire; Mr.Cardwell, M.P., Mr. Hamilton, consul of her

Britannic Majesty; Baron de Chivenet, commandant of the garrison at

Boulogne; M. de Hestingham, king’s advocate at Boulogne: M. Dessaux,

Captain Barthelemy, Mr. F. Cubitt, Captain Charlwood, R.N., Captain

Peat, R.N., General Hodgson, M. de la Porte, &c., the directors of

the railway, &c. The company, in addition to the good things placed

on the tables, were entertained by a musical band from Boulogne,

which, during the breakfast, played some of the national airs of

England and France.

The mayor of Boulogne gave the first toast, viz., “the health of her

Majesty Queen Victoria" which was drunk with the honours. The mayor

of Folkestone then proposed “the health of his Majesty Louis

Philippe," which was also received with cheers, and drunk with all

the honours. The next toast, “the Royal Families of England and

France," was the third in succession, and was drunk with the

honours, after which the health of “the Mayor of Folkestone," was

proposed and drunk, and the mayor returned thanks. On the health of

“the Mayor of Boulogne" being drunk, which came next in succession,

M. Adam, in returning thanks, detailed the history of the projected

railroad from Paris to Boulogne through the French Chambers, and

observed that the recent fete given at Boulogne on occasion of the

railroad and steam boat excursion from London to that city, had had

a beneficial effect in showing what could be done by railroads and

steamers, and bad expedited the wished-for proceedings. M. Adam

repudiated all intention of injuring Calais by supporting a

communication between Boulogne and Folkestone, and said there was

sufficient traffic for both ports, and enough to render the

competition of the one no injury to the other.

On the health of Mr. Baxendale and the Directors of the Smith

Eastern Railroad being drunk, that gentleman returned thanks, and in

doing so described the state of Folkestone harbour from the printed

report and memorial laid before the commissioners of Her Majesty's

Treasury by the merchants, shipowners, and masters of ships of the

port of London. Mr. Baxendale said he considered the interests of

the four ports of Boulogne, Calais, Dover, and Folkestone, would all

be advanced by the more rapid communication of railroads, and that

it was not from the injury of any one of them that the others should

receive increased advantages. He then briefly adverted to the state

of the harbour of Folkestone before it was purchased by the railroad

company; and pointed out the capabilities it possessed, and the

improvement of which it was susceptible. He hoped the example set to

the government of the country by the company would lie productive of

good effects in calling their attention to what might be done to

render other harbours better than they now were. Mr. Baxendale

concluded amidst loud cheering.

The healths of Mr. Marjoribanks, Mr. Bleaden, and several others

were then drunk, and those gentlemen returned thanks. After which a

large portion of the company retired in order to return to London by

the train. The festivities were, however, not over till a late hour,

and it was nearly midnight before the steamer conveyed the French

guests back to Boulogne.

|

|

Kentish Gazette 8 August 1843.

The South Eastern Railway Fete at Folkestone.

On Tuesday the mayor and corporation of Folkestone, and the directors of

the Dover and South Eastern Railway Company, celebrated the opening of

the communication by regular steam-packets between the ports of

Folkestone and Boulogne by a public breakfast and other festivities at

the South Eastern Pavilion Tavern at Folkestone. The town was filled all

day long with visitors from the adjacent places, and by arrivals from

London, to be present at the celebration. The vessels in the harbour,

which has been purchased by the railway company, and which it is in

contemplation to enlarge and improve forthwith, were decorated with

flags and ensigns, and presented a very gay appearance, whilst from the

old lower of the church the bells rang forth a merrv peal. At half-past

tweIve o' clock the City of Boulogne steamer came into the harbour and

landed the mayor and authorities of Boulogne, and the gentlemen of that

place invited to be present at the festival. Their arrival was announced

by a salute of ordnance, and they were received on landing by the mayor

and corporation of Folkestone and conducted to the terminus of the

railway, where they inspected the engines, carriages, &c, and expressed

their satisfaction with the arrangements. About this time the down train

from London came in, having brought down several of the directors and

many more guests to the breakfast. In the earlier part of the day the

Sir William Wallace steamer, one of the eight new vessels intended to

make the passage between Boulogne and Folkestone, had arrived from

London, and taken from Folkestone to Boulogne in this her first trip

upwards of one hundred passengers, and another vessel shortly afterward

came in from Boulogne with a large number of passengers. It appears that

the harbour of Folkestone in its present state contains at high tide

water to the depth of twenty feet, and that when the wind is south or

south-west it affords a better entrance for vessels than Dover.

By four o'clock the town was filled with people, and the two mayors, and

those by whom they were attended, the directors and the visitors having

returned from the railroad, the breakfast commenced. In order to afford

accommodation to the very numerous party assembled, and to the various

groups collected together, an elegant marquee, sent down for the

occasion from the manufactory of Mr. B. Edgington, of Duke Street,

Borough, had been erected in front of the Pavilion Tavern, facing the

sea, and beneath this were placed seats and tables; and ii addition to

this a building, formerly a beat house, had been converted into a

banqueting, room, and fitted up with great taste bv Mr. Vanlini, the

proprietor of the Tavern, to whom it is but justice to say that his

arrangements for the gratification ot his guests were most satisfactory.

The repast, to which nearly two hundred persons sat down at four

o'clock, was in a very excellent style The chair was taken by the mayor

of Folkestone, supported on his right hand by Mr. Baxendale, and on his

left by M. Adam, the mayor of Boulogne. There were also present. Mr.

Marjoribanks, M.P. for Folkestone; M. Bailly, commandant of the

artillery ait Boulogne; M. De là Sabloniere, lieutenant colonel of the

national guard of that city; M. De Mentque, sub-prefect; M. Sanson,

colonel of the national guard; Capt. Tyndall, M. Marquet, civil engineer

at Boulogne; M. Le Comte, grand vicaire; Mr.Caidwell, M.P., Mr.

Hamilton, consul of her Britannic Majesty; Baron de Chivenet, commandant

of the garrison at Boulogne; M. de Hestingham, king’s advocate at

Boulogne: M. Dessaux, Captain Barthelemy, Mr. F. Cubitt, Captain

Charlwnod, R.N., Captain Pent, R.N., General Hodgson, M. de la Porte,

&c., the directors of the railway, &c. The company, in addition to the

good things placed on the tables, were entertained by a musical band

from Boulogne, which, during the breakfast, played some of the national

airs of England and France.

The mayor of Boulogne gave the first toast, viz., “the health of her

Majesty Queen Victoria" which was drunk with the honours. The mayor of

Folkestone then proposed “the health of his Majesty Louis Philippe,"

which was also received with cheers, and drunk with all the honours. The

next toast, “the Royal Families of England and France," was the third in

succession, and was drunk with the honours, after which the health of

“the Mayor of Folkestone," was proposed and drunk, and the mayor

returned thanks. On the health of “the Mayor of Boulogne" being drunk,

which came next in succession, M. Adam, in returning thanks, detailed

the history of the projected railroad from Paris to Boulogne through the

French Chambers. and observed that the recent fete given at Boulogne on

occasion vf the railroad and steam boat excursion from London to that

city, had had a beneficial effect in showing what could be done by

railroads and steamers, and bad expedited the wished-for proceedings. M.

Adam repudiated all intention of injuring Calais by supporting a

communication between Boulogne and Folkestone, and said there was

sufficient traffic for both ports, and enough to render the competition

of the one no injury to the other.

On the health of Mr. Baxendale and the Directors of the Smith Eastern

Railroad being drunk, Ihat gentleman returned thanks, and in doing so

described the state of Folkestone harbour from the printed report and

memorial laid before the commissioners of Her Majesty's treasury by the

merchants, shipowners, and masters of ships of the port ol London. Mr.

Bnxemhile said he considered the interests of the four ports of

Boulogne, Calais, Dover, and Folkestone, would all be advanced by the

more rapid communication of railroads, and that it was not from the

injury of any one of them that the others should receive increased

advantages. He then briefly adverted to the state of the harbour of

Folkestone before it was purchased by the railroad company; and pointed

out the capabilities it possessed, and the improvement of which it was

susceptible. He hoped the example set to the government of the country

by the company would lie productive of good effects in calling their

attention to what might be done to render other harbours better than

they now were. Mr. Baxendale concluded amidst loud cheering.

The healths of Mr. Marjoribanks, Mr. Bleaden, and several others were

then drunk, and those gentlemen returned thanks. After which a large

portion of the company retired in order to return to London by the

train. The festivities were, however, not over till a late hour, and it

was nearly midnight before the steamer conveyed the French guests back

to Boulogne.

|

|

Kentish Gazette 5 September 1843.

A great many workmen are now employed in forming the Railway to the

Harbour; upwards of twenty houses are already down, and many more will

be removed in a short time. The contractor for clearing the harbour has

put on more men, who work night and day. As soon as the mud and shingle

are cleared out, other contracts are ready to be let. Messrs. Grissel

and Peto are building a large hotel, which will contain a great number

of bedrooms; its situation is fronting the harbour, on what was called

Farley’s Ground, close by the Pavilion. The pier is being made wider,

and is lighted with gas, which is a great improvement. The company seems

“to stand for nothing” - whatever is wanted is done.

|

|

Kentish Gazette 21 November 1843.

Mr. Major, on his re-election to the office of Mayor on the 9th inst.

invited the Town Council, and Joseph Baxendale, Esq. the chairman of the

South Eastern Railway, to a breakfast, a la fourchette, at the Pavilion.

The Mayor and Corporation, and a party of gentlemen, afterwards dined

together at the Rose Hotel.

|

|

Kentish Gazette 28 November 1843.

The new hotel and harbour house are now nearly completed. The tramway

from the station to the harbour will shortly be finished. It is expected

the trains will now run to the permanent station.

|

|

From the Dover Telegraph and Cinque Ports General

Advertiser, Saturday 20 January, 1844. Price 5d.

It is said that another Hotel is to be erected here, on the site of

the "Pavilion," 150ft larger than the recently built one.

|

|

Kentish Gazette 23 January 1844.

The improvements of this place had been for two or three weeks nearly at

a standstill, but considerable activity is again evinced in the progress

of the works, and a good number of hands are employed on the branch tram

road from the station to the harbour, which is rapidly approaching

completion. The clearing out of the mud and stones from the bed of the

harbour is finished, and the depth of water much increased, but this has

had a serious effect in increasing the shingle bank at the mouth, which

has caused considerable obstruction to vessels entering or leaving the

port. The company, however, intend to carry out their work with spirit,

and a large space is laid out for the purpose of forming a capacious

back water bay, the effect of which will be to prevent the bar from

forming at the mouth. An act is about to be applied for to enable the

company to do this, of which notice has been given to the inhabitants of

500 houses in the lower part of Folkestone, the whole of which houses

are to be taken down. The new pavilion facing the harbour has been

opened to the public by the company. It is a fine building, replete with

every accommodation, and capable of making up a hundred beds. Baths are

fitted up on a superior construction, which, as well as the whole house,

are supplied with water from a deep well sunk on the premises, the water

from which is conveyed into every department on the hydraulic principle.

The new harbour house is nearly completed. It is a handsome building,

surmounted by a square lower, in which an illuminated clock with four

faces is now being placed. The lawn in front of the pavilion has been

neatly laid out, and well turfed down, which gives it a gay and cheerful

appearance. The trains now run over the viaduct to the permanent

station, which is in every way commodious, and stands in an excellent

situation to command the communication with every part of the town, the

Dover road and the adjoining country. Well-horsed omnibuses are plying

to and from the station, the harbour, Dover, Sandgate, Hythe, &c.; and

the communication between this place and the continent is rendered

expeditious and safe, by the establishment of steamboats, which leave

and arrive in the harbour every tide to and from Boulogne. An excellent

road, lit with gas, has been constructed from the station to the

harbour, with a raised footpath, which renders the communication with

the lower part of the town easy and safe. This place is rapidly

progressing in importance, the effects of which are every day apparent

in the rapidly increasing value of property, and there is no doubt it

will soon become a port of considerable consequence. There are many

opinions afloat respecting the probable time when the line will be

opened to Dover; but whenever that may be, there is no reason why this

port may not become the grand outlet to the continent. A great

proportion of travellers will prefer the shorter and more expeditious

route by Boulogne, which is not only a saving of time and distance, but

a saving of expense, and will be preferred to the more circuitous route

by Dover and Calais. The whole aspect of the town has much improved of

late, and the streets (which are lit with gas) are much better kept and

cleaner swept than formerly.

|

|

West Kent Guardian 3 February 1844.

The old Pavilion Hotel is in course of demolition, and we hear that

another large building will be erected to match the new Pavilion. A

handsome parapetted wall is building in front of the hotel, which

encloses the lawn, and enhances the appearance of the harbour.

|

|

Kent Herald 8 February 1844

The new "Pavilion Hotel": The old building is fast being razed to the ground, and

an extensive enlargement of this new hotel is in progress. The workmen are

sinking the foundation, and the works are commenced towards building a large and

handsome wing to the hotel on the site of the old building, which will have a

fine appearance in conjunction with the present hotel and harbour house, and

present a splendid range of edifices to grace our neat and commodious harbour.

|

|

West Kent Guardian 16 March 1844.

The improvements and buildings at the new Pavilion are in progress,

and the newly-turfed lawn in front gives it now a very pretty and

imposing aspect. Some new buildings are also about to be erected in

the place, and we hope soon to see the activity of Folkestone return

and its present dullness dissipated.

|

|

Canterbury Weekly Journal 25 May 1844.

The building of the new "Pavilion Hotel" is going on very rapidly and,

when completed, it will be, probably, the finest hotel on the coast.

|

|

Dover Chronicle 25 May 1844.

The addition to the new Pavilion Hotel is proceeding with

expedition; when completed it will rival the best hotel in England,

or on the Continent. The addition comprises billiard room, coffee

room, ballroom, a large club room, a table d'hote; a large balcony

will run along the front, consisting of York slabs six feet wide,

supported by large iron ornamental brackets, which have a rich

appearance. Altogether the building, when completed, will be an

ornament to our town, and reflects great credit on the architect and

the railway company.

|

|

Dover Telegraph 25 May 1844.

On Tuesday, a man employed in pulling down the old Pavilion trod

upon a board, which canted up and precipitated him several feet to

the ground, by which he was much bruised, but, fortunately, no bones

were broken. The man is a sawyer by trade, but work being slack he

was temporarily employed as a labourer.

|

|

Kentish Mercury 1 June 1844.

An accident happened to one of the workmen, named Johnson

Herbert, at the New Pavilion, on Wednesday last, by treading on a

piece of timber, which gave way with him and precipitated him from a

height of 12 to 14 feet. The poor fellow was considerably hurt, but

is recovering.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 14 January 1845.

The new, or northern, wing of the great Pavilion Hotel is now

finished, and will soon be open to the public. The western wing of

that immense establishment has, ever since its opening, enjoyed a

good patronage and, no doubt, the whole establishment will be

unequalled for beauty and convenience, from its interior

arrangements and good management.

The new Royal George Hotel is also completed, and will soon be open.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 22 April 1845.

The Royal George hotel, we have heard, will be occupied in May next.

This has now become absolutely necessary, the Pavilion Hotel, large

as it is, being frequently obliged to “billet” travellers on its

neighbours.

|

|

Kent Herald 27 June 1844

The approach to the harbour has been much improved by the demolition of the

house at a narrow and dangerous corner (late the Victoria Inn), which will widen

the road by ten feet at this point, and improve the appearance of the harbour.

The building at the "Pavilion Hotel" is going on satisfactorily, and when

completed will render it the most extensive, and handsomest hotel, on this side

of the Channel.

|

|

Kent Herald 23 January 1845

The new, or northern, wing of the great "Pavilion Hotel" is now finished, and will

soon be open to the public. The western wing of that immense establishment has,

ever since its opening, enjoyed a good patronage and, no doubt, the whole

establishment will be unequalled for beauty and convenience, from its interior

arrangements and good management.

The new "Royal George Hotel" is also completed, and will be soon open.

There is also a row of houses near Grove House School, sixteen in number, with a

large building opposite, intended for an inn.

|

|

Kent Herald 24 April 1845

The "Royal George Hotel," we have heard, will be occupied in May next. This has

now become absolutely necessary; the "Pavilion Hotel," large as it is, being

frequently obliged to “billet” travellers on its neighbours.

|

|

From the Kentish Gazette, 27 May 1845.

PAVILION HOTEL, FOLKESTONE.

THE present Proprietor of this Hotel (Mr. Vantini having ceased to be

Proprietor thereof), begs to inform the Nobility, Gentry, and Public

that this Establishment affords accommodation of a most superior

character for Families, Visitors, and Travellers to the Continent, with

a scale of charges that will be found as moderate as any first-class

Hotel in the kingdom. The Cuisine is under the management of eminent

foreign Cooks, and the Wines, which are of the highest order, are now

wholly supplied by a first-rate and old-established House in the City,

the former stock having been entirely removed.

PARIS via FOLKESTONE and BOULOGNE. — The Hotel is also situated close to

the Quay, where the steamers (which go from Folkestone to Boulogue and

back daily) land their Passengers. It need hardly be observed that this

is the shortest and best route to and from Boulogne, avoiding the

numerous Tunnels that lie beyond. Folkestone on the Dover Line, whilst

the present Boulogne steamers on this station, the Queen of the Belgians

and the Princess Maude, being first-class Vessels, are, unrivalled in

speed, safety, and accommodation. The present Proprietor is happy to say

that although Mr. Vantini has ceased to be the Proprietor of this Hotel,

he will still have the valuable assistance of himself and Mad. Vantini

in the management of the same; and families and others requiring rooms

or information, are requested to address letters to Mad. Vantini,

"Pavilion Hotel," Folkestone.

|

|

Dover Telegraph 31 May 1845.

Advertisement: The present Proprietor of this Hotel (Mr. Vantini

having ceased to be Proprietor thereof), begs to inform the

Nobility, Gentry, and Public that this Establishment affords

accommodation of a most superior character for Families, Visitors,

and Travellers to the Continent, with a scale of charges that will

be found as moderate as any first-class Hotel in the Kingdom. The

Cuisine is under the management of eminent foreign Cooks, and the

Wines, which are of the highest order, are now wholly supplied by a

first-rate and old-established House in the City, the former stock

having been entirely removed.

Paris via Folkestone and Boulogne - The Hotel is also situated close

to the Quay, where the steamers (which go from Folkestone to

Boulogne and back daily) land their Passengers. It need hardly be

observed that this is the shortest and best route to and from

Boulogne, avoiding the numerous tunnels that lie beyond Folkestone

on the Dover Line, whilst the present Boulogne steamers on this

station, the Queen of the Belgians and the Princess Maude, being

first-class Vessels, are unrivalled in speed, safety, and

accommodation. The present Proprietor is happy to say that although

Mr. Vantini has ceased to be the Proprietor of this Hotel, he will

still have the valuable assistance of himself and Mad. Vantini in

the management of the same; and families and others requiring rooms

or information, are requested to address letters to Mad. Vantini,

Pavilion Hotel, Folkestone.

|

|

Kentish Gazette 23 September 1845.

Folkestone, Sept. 22: The traffic between this place and Boulogne

during the past week has been immense, and notwithstanding the

violent gales, only on one day interrupted. We hear that it is

contemplated to erect increased accommodation for the public by

extending considerably the "Pavilion Hotel," for although the "Royal

George Hotel" is opened and in full business there is yet a want of

means to meet the tide of demand, which is daily increasing here.

|

|

From the Dover Telegraph and Cinque Ports General Advertiser, Saturday, 23 May, 1846. Price 5d.

FOLKESTONE

On Thursday week the new burial ground attached to Folkestone Church

(presented by the Earl of Radnor,) was consecrated by his Grace the

Archbishop of Canterbury, who was attended by the Venerable Archdeacon

Croft and the clergy of the district. Owing to the very unfavourable

state of the weather, but few spectators were present to view the

ceremony. The Archbishop, Archdeacon, and several clergymen and

gentlemen, afterwards adjourned to the “Pavilion Hotel,” when an

excellent dinner was prepared for them.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 1 September 1846

Town Hall, Tuesday: This being the licensing day for this town, all

the licenses were renewed, and an additional licence was granted to

Mr. Zenon Vantini, for the Pavilion tap.

Note: Pavilion Hotel.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 4 May 1847

Petty Sessions, Tuesday; Before Capt. W. Sherren, Mayor, D. Major &

S. Bradley Esqs.

Louis Turiam, waiter at the Pavilion Hotel, was summoned by Henry

William Mayne (a man who gets his living by singing at public

houses), for an assault. The complainant stated that he entered the

hotel with some friends and called for wine, and that for some

offence given he was turned out of the house and struck by the

defendant, without provocation; he was perfectly sober at the time.

The defendant, in answer to the charge, stated that the complainant

came to the hotel and called for wine; that while there he conducted

himself in a disgraceful manner – so much so that several ladies and

gentlemen complained of his conduct to the manager. Finding he was

much intoxicated and refused to be quiet, he, with assistance,

turned him out of the hotel. Defendant then went outside, and while

looking at the complainant, who was still creating a disturbance, he

was struck by him on the mouth; he defended himself from a second

attack of the complainant, who was ultimately locked up in the

station-house.

Walsh, the night porter, corroborated the defendant's statement in

every particular, and stated that the complainant was very tipsy.

The Magistrates consulted together, and decided that the assault was

justified, and dismissed the summons.

|

|

Dover Chronicle 8 May 1847

At the Folkestone Petty Sessions last week, Louis Turiam, waiter at

the Pavilion Hotel, was summoned by Henry William Mayne

(professional singer), for an assault. The complainant stated that

he entered the hotel with some friends and called for wine, and that

for some offence given he was turned out of the house and struck by

the defendant, without provocation; he was perfectly sober at the

time.

The defendant, in answer to the charge, stated that the complainant

came to the hotel and called for wine; that while there he conducted

himself in a disgraceful manner – so much so that several ladies and

gentlemen complained of his conduct to the manager. Finding he was

much intoxicated and refused to be quiet, he, with assistance,

turned him out of the hotel. Defendant then went outside, and while

looking at the complainant, who was still creating a disturbance, he

was struck by him on the mouth; he defended himself from a second

attack of the complainant, who was ultimately locked up in the

station-house.

Walsh, the night porter, corroborated the defendant's statement in

every particular, and stated that the complainant was very tipsy.

The Magistrates consulted together, and decided that the assault was

justified, and dismissed the summons.

|

|

West Kent Guardian 8 May 1847

Petty Sessions, Tuesday; Before Capt. W. Sherren, Mayor, D. Major &

S. Bradley Esqs.

Louis Turiam, waiter at the Pavilion Hotel, was summoned by Henry

William Mayne (a man who gets his living by singing at public

houses), for an assault. The complainant stated that he entered the

hotel with some friends and called for wine, and that for some

offence given he was turned out of the house and struck by the

defendant, without provocation; he was perfectly sober at the time.

The defendant, in answer to the charge, stated that the complainant

came to the hotel and called for wine; that while there he conducted

himself in a disgraceful manner – so much so that several ladies and

gentlemen complained of his conduct to the manager. Finding he was

much intoxicated and refused to be quiet, he, with assistance,

turned him out of the hotel. Defendant then went outside, and while

looking at the complainant, who was still creating a disturbance, he

was struck by him on the mouth; he defended himself from a second

attack of the complainant, who was ultimately locked up in the

station-house.

Walsh, the night porter, corroborated the defendant's statement in

every particular, and stated that the complainant was very tipsy.

The Magistrates consulted together, and decided that the assault was

justified, and dismissed the summons.

|

|

Dover Telegraph 21 July 1849

Advertisement: Folkestone, Kent, to be sold by auction, at the

"Pavilion Hotel," in Folkestone, on Saturday, July 28th, 1849, at

three o'clock in the afternoon (by order of the mortgagee, under

powers of sale), subject to such conditions as will be then and

there produced:-

All that messuage or tenement, known by the name of the "York Hotel,"

situate in the Dover Road, in the town of Folkestone.

The property is held under a lease from the Earl of Radnor and

Viscount Folkestone for a term of 99 years, from the 24th day of

June, 1844, subject to the annual rent of £11 5s., and to the

covenants and agreements contained in such lease.

The premises are well situated, are very capacious, and are

constructed with a view to being easily converted into two large and

commodious family residences. Immediate possession of the property

can be given.

To view the premises apply to the Auctioneer, and for further

particulars to Mr. Chalk, or Messrs. Gravener and Sons, Solicitors,

Dover, or to Messrs. Brockman and Watts, Solicitors, Folkestone.

July 12th, 1849

|

|

Kent Herald 9 August 1849

Petty Sessions:

July 28, at the Pavilion Hotel, Folkestone, by Mr. M. M. Major: the York Hotel,

Folkestone, put up at £800 (no bidders).

|

|

Kentish Gazette, 14 August 1849.

Public Sales.

July 28, at the "Pavilion Hotel," Folkestone, by Mr. M. M. Major;

Freehold estate, Cheriton, near Folkestone, with 22 acres of arable and

meadow land, sold for £1,520; freehold residence and acre of pasture

land, in the Upper Sandgate-road, £1,800 (bought in); freehold messuages,

Dover-road, £500 (bought in); freehold pasture land, two acres, near

Dover-road, Folkestone, sold for £385, to Mr. John Jeffery, whose

property it adjoins; the "York Hotel," Folkestone, put up at £800 (no

bidders). — July 21, by Messrs. Farebrother and Co., at Garraway's:

Freehold farm, called Clinch-street, Hoo, Kent, let for £300, knocked

down at £8,400.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 2 October 1849

Petty Sessions, Monday; Before C. Golder Esq., Mayor.

John Cane was charged with breaking a window at the Pavilion Hotel.

From the evidence of the manager, Gullous Gianini, it appeared that

the prisoner was playing a flute at the south end of the building;

he was requested to go away by one of the waiters sent out by a lady

in the hotel; he refused, and threw his flute at the waiter's head, which it missed, and went through a square of glass. The

prisoner was intoxicated. Fined 5s/ and costs, or fourteen days' hard labour.

Committed.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 1 January 1850

Petty Sessions, Friday; Before W. Major, C. Golder and S. Mackie

Esqs.James Osborne, chimney sweep, and Osborne Lee, ostler at the Duke's

Head, Hythe, were charged with stealing a piece of copper, the

property of Owen Tickel Alger Esq., of the Pavilion Hotel.

John Myers, marine store dealer, being sworn, deposed: I live at

Hythe. On the 19th December instant the prisoner Osborne Lee brought

me the piece of copper produced, and asked me to purchase it. I

asked him where he obtained it, and he said it was all right, I need

not be afraid. I told him I thought it was not all copper, and that

I would give him 4s., and if when I sold it they did not knock

anything off I would give him more; it weighed 13 lbs.

Mary Roker deposed: I am still-room maid at the Pavilion Hotel. The

piece of copper produced was formerly used in the bain-marie, in the

still-room, to keep things hot. We have no use for it now, but I

have fitted it in its former place, and can swear to it by the make

of it.

William Francis Smith deposed: The article now produced was made by

my father for the bain-marie. I can swear to it as I cut the hole in

it to let out the steam. The value of it as old copper is about 9s.;

it cost new about 26s.

Richard Bishop, chimney sweeper, deposed: I lodge at the Duke's Head, Hythe. About the 15th or 16th instant the prisoner, James

Osborne, came into the Duke's Head, and enquired for me; I shortly

after saw him, when he asked me if I would purchase some old copper;

he said he had about 12lbs. or 14 lbs. I was afraid to buy it, and

told him to take it to my master, Mr. Myers. I did not see it till

my master showed it to me. The prisoner Osborne Lee told me he had

sold it for the other prisoner, and got 4s. for it, and 6d. for his

own trouble.

The Magistrates consulted, and the prisoner Osborne Lee was then

sworn as a witness; he deposed: The prisoner (James Osborne) brought

me a piece of copper into the tap room of the Duke's Head, said he

had found it on the sea shore, and wished me to sell it for him. I

told him I would try and sell it for him if it was all right; he

assured me it was, and that I need not be afraid. I took it to Mr.

Myers, and he gave me 6d. for my trouble. I was asked by Mr. Myers

where I got it from, and I told him it was all right.

The prisoner, in defence, said: When I had done my work a few days

before I gave the copper to the ostler. My master, Mr. Driscoll,

chimney sweeper, sent me over from Hythe to the Pavilion to empty

sawdust and bring back ashes. One of my master's men was at work at

the hotel all the morning. When I got there he was lying in the

ash-hole, awaiting my coming. I gave him the basket down to fill,

and he shortly handed me the copper from out of the sawdust, and

said it would fetch a shilling or two. I asked him who it belonged

to, and he said to them, the sweeps. I told him he had better not

carry it away, for fear of getting themselves and master into

trouble. He said whatever was in there was to throw away, or carry

home. Being a perfect stranger to the work and house, I did not know

what the sweeps were allowed to have. He told me it was all right;

we then took it home, and afterwards I employed the ostler to sell

it for us, and we were to divide the money.

Remanded till Tuesday. A warrant was issued in the course of the day

for the apprehension of the other man concerned in the robbery.

|

|

Kent Herald, 3 January 1850.

Petty Sessions: James Osborne, a chimney sweep, and Osborne Lee, ostler at the

"Duke's Head," Hythe, were charged with stealing a piece of copper, the property

of Owen Tickel Algar Esq., of the "Pavilion Hotel." Remanded. A warrant was issued

in the course of the day for the apprehension of another man concerned in the

robbery.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 8 January 1850

Petty Sessions, Tuesday; Before D. Major Esq., Mayor, C. Golder, W.

Major and S. Mackie Esqs.

James Osborne and Thomas Graham, the former remanded from last week,

were brought up in custody for final examination, charged with

stealing a piece of copper from the Pavilion Hotel. The prisoner

Graham had been apprehended at Canterbury by police constable

Pearson, who has shown much vigilance in the matter. The statement

made last week by Osborne was read to the prisoner Graham.

Police constable Pearson stated that on Christmas Day last he looked

in at Mr. Myers's, the marine store dealer, and seeing the piece of copper asked him

where he bought it; he gave the name of the ostler at the Duke's Head, Hythe. Witness then took him and the other

prisoner into custody on Saturday last; on the 29th he apprehended

Thomas Graham at Canterbury.

The prisoner Graham, in his defence, stated that he always took the

rubbish away and put it on the beach; he did not know it was copper

when he took it away.

Committed to the Quarter Sessions.

|

|

Kent Herald, 10 January 1850.

Petty Sessions: James Osborne and Thomas Graham, the former remanded from last

week, were brought up in custody for final examination, charged with stealing a

piece of copper from the "Pavilion Hotel." The prisoner Graham had been

apprehended at Canterbury by police constable Pearson, who has shown much

vigilance in the matter. Committed to the Quarter Sessions.

The "Pavilion Hotel" changes hands next week. We understand that it has been taken

by Mr. Breach, of the firm of Bathe and Breach, of the "London Tavern," Bishopsgate Street.

|

|

Dover Chronicle 12 January 1850

The Pavilion Hotel changes hands next week. We understand that it

has been taken by Mr. Breach, of the firm of Bathe and Breach, of

the London Tavern, Bishopsgate Street.

|

|

Canterbury Journal 12 January 1850.

On Tuesday last, the quarter sessions for the borough of Folkestone

were holden at the Guildball, Folkestone, before the Recorder (J. J.

Lonsdale, Esq.,) the Mayor (D. Major, Esq.,) and Messrs. C. Golder,

Wm. Major, and S. Bateman, magistrates.

James Osborne, labourer, late of Hythe, was indicted for having

stolen a piece of copper, value 9d., the property of Mr. Owen

Fickell Algar, proprietor of the "Pavilion Hotel."

Guilio Giovarni, manager of the "Pavilion Hotel," deposed that the

piece of copper was brought to him by Pearson, the policeman, and

which he recognised as being the top of a “bain marie” It had not

been used for two years; originally coat 25s.; and had been put away

in the scullery.

Matthew Pearson, policeman, on the 25th of December, went to John

Myers, the marine store dealer, at Hythe, in consequence of

information he had received; saw the piece of copper produced; asked

where it came from; was told by Myers that he had purchased it from

the ostler of the "Duke’s Head Inn," named Osborn Lee; took it away

and brought it home; next day took it to the "Pavilion Hotel," where

the servants identified it as being the property of Mr. Algar.

John Myers, marine-store dealer, deposed that Osborn Lee, ostler of

the "Duke’s Head," brought the piece of copper produced; asked him how

he came by it; said it was all right; told him all right was

sometimes all wrong; gave him 4s. for it, but told him he might have

the difference in the price, if any, at some future time; did not

know the exact value; told him, over and over again, he was afraid

it was stolen.

The Recorder cautioned this witness about his dealings, and told him

to be more cautious in future.

Osborn Lee, ostler at the "Duke’s Head," Hythe, deposed to selling the

piece of copper for Osborne, without any suspicion that it had been

stolen.

Mary Roker, still-room maid at the hotel, identified the copper as

belonging to the “bain marie” at the "Pavilion." Saw it last in the

still-room, two or three years since.

William Francis, whitesmith, identified the copper produced, it

being fitted by him in the place it occupied.

The prisoner, on being asked what he had to say, stated that about a

fortnight ago he was sent for a load of ashes. One of his master's

sweeps was down the ash-hole at the "Pavilion Hotel;" he passed the

piece of copper through the hole, and when be (prisoner) cautioned

him about it, he said all thrown in there belonged to the sweeps.

The sweep asked him to sell it for him, and he passed it to Osborn

Lee for the purpose.

The Recorder summed up, and the jury, having retired for a short

time, acquitted the prisoner. He was, however, detained in custody,

to be brought up as evidence against the sweep.

James Graham, the sweep alluded to in the previous trial, was then

indicted for having stolen the piece of copper, value 9s., and

pleaded Not Guilty.

The evidence in this case was precisely as before, with the addition

of James Osborn's statement as to the conversation between him and

the sweep, and his undertaking to sell the item in question.

Witnesses were called to speak to character.

Verdict: Guilty – one month's imprisonment.

|

|

Kentish Gazette, 15 January 1850.

FOLKESTONE.

The "Pavilion Hotel" is about to change hands. We understand that it has

been taken by Mr. Breach, of the firm of Battle and Breach, of the

"London Tavern," Bishopsgate-street.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 15 January 1850

Quarter Sessions: Before J. Lonsdale Esq., Recorder.

James Osborne, labourer, was indicted for stealing a piece of

copper, value 9s., from the Pavilion Hotel.

Not Guilty.

|

|

Kentish Gazette, 15 January 1850.

QUARTER SESSIONS.

On Tuesday last, the quarter sessions for the borough of Folkestone

were holden at the Guildhall, Folkestone, before the Recorder (J. J.

Lonsdale, Esq.,) the Mayor (D. Major, Esq.,) and Messrs. C. Golder, Wm.

Major, and S. Bateman, magistrates.

James Osborne, labourer, late of Hythe, was indicted for having

stolen a piece of copper, value 9s., the property of Mr. Owen Fickell

Algar, proprietor of the "Pavilion Hotel."

Guilio Giovarni, manager of the "Pavilion Hotel," deposed that the

piece of copper was brought to him by Pearson, the policeman, and which

he recognised as being the top of a "bain marie." It had not been used

for two years; originally coat 25s.; and had been put away in the

scullery.

Matthew Pearson, policeman, on the 25th of December, went to John

Myers, the marine store dealer, at Hythe, in consequence of information

he had received; saw the piece of copper produced; asked where it came

from; was told by Myers that he had purchased it from the ostler of the

"Duke’s Head Inn," named Osborn

Lee; took it away and brought it home; next day took it to the "Pavilion

Hotel," where the servants identified it as being the property of Mr.

Algar.

John Myers, marine-store dealer, deposed that Osborn Lee, ostler of

the "Duke’s Head," brought the

piece of copper produced, asked him haw he came by it, said it was all

right, told him all right was sometimes all wrong; gave him 4s. for it,

but told him he might have the difference in the price, if any, at some

future time; did not know the exact value, told him, over and over

again, he was afraid it was stolen.

The Recorder cautioned this witness about his dealings, and told him

to be more cautious in future.

Osborn Lee, ostler at the "Duke's

Head," Hythe, deposed to selling the piece of copper for Osborne,

without any suspicion that it had been stolen.

Mary Roker, still-room maid at the hotel, identified the copper as

belonging to the "bain marie" at the "Pavilion." Saw it last in the

still-room, two or three years since.

William Francis, whitesmith, identified the copper produced, it being

fitted by him in the place it occupied.

The prisoner, on being asked what he had to say, stated that about a

fortnight ago he was sent for a load of ashes. One of his master's

sweeps was down the ash-hole at the "Pavilion Hotel"; he passed the

piece of copper through the hole, and when he (prisoner) cautioned him

about it, he said all thrown in there belonged to the sweeps. The sweep

asked him to sell it for him, and he passed it to Osborn Lee for the

purpose.

The Recorder summed up, and the jury, having retired for a short

time, acquitted the prisoner. He was, however, detained in custody, to

be brought up as evidence against the sweep.

|

|

Kent Herald, 17 January 1850.

On the 8th inst., the quarter sessions for the borough of Folkestone were holden

at the Guildball, Folkestone, before the Recorder (J. J. Lonsdale, Esq.,) the

Mayor (D. Major, Esq.,) and Messrs. C. Golder, Wm. Major, and S. Bateman,

magistrates.

James Osborne, labourer, late of Hythe, was indicted for having stolen a piece

of copper, value 9d., the property of Mr. Owen Fickell Algar, proprietor of the

Pavilion Hotel.

Guilio Giovarni, manager of the Pavilion Hotel, deposed that the piece of copper

was brought to him by Pearson, the policeman, and which he recognised as being

the top of a “bain marie” It had not been used for two years; originally coat

25s.; and had been put away in the scullery.

Matthew Pearson, policeman, on the 25th of December, went to John Myers, the

marine store dealer, at Hythe, in consequence of information he had received;

saw the piece of copper produced; asked where it came from; was told by Myers

that he had purchased it from the ostler of the Duke’s Head Inn, named Osborn

Lee; took it away and brought it home; next day took it to the Pavilion Hotel,

where the servants identified it as being the property of Mr. Algar.

John Myers, marine-store dealer, deposed that Osborn Lee, ostler of the Duke’s

Head, brought the piece of copper produced; asked him how he came by it; said it

was all right; told him all right was sometimes all wrong; gave him 4s. for it,

but told him he might have the difference in the price, if any, at some future

time; did not know the exact value; told him, over and over again, he was afraid

it was stolen.

The Recorder cautioned this witness about his dealings, and told him to be more

cautious in future.

Osborn Lee, ostler at the Duke’s Head, Hythe, deposed to selling the piece of

copper for Osborne, without any suspicion that it had been stolen.

Mary Roker, still-room maid at the hotel, identified the copper as belonging to

the “bain marie” at the Pavilion. Saw it last in the still-room, two or three

years since.

William Francis, whitesmith, identified the copper produced, it being fitted by

him in the place it occupied.

The prisoner, on being asked what he had to say, stated that about a fortnight

ago he was sent for a load of ashes. One of his master’s sweeps was down the

ash-hole at the Pavilion Hotel; he passed the piece of copper through the hole,

and when be (prisoner) cautioned him about it, he said all thrown in there

belonged to the sweeps. The sweep asked him to sell it for him, and he passed it

to Osborn Lee for the purpose.

The Recorder summed up, and the jury, having retired for a short time, acquitted

the prisoner. He was, however, detained in custody, to be brought up as evidence

against the sweep.

James Graham, the sweep alluded to in the previous trial, was then indicted for

having stolen the piece of copper, value 9s., and pleaded Not Guilty.

The evidence in this case was precisely as before, with the addition of James

Osborn's statement as to the conversation between him and the sweep, and his

undertaking to sell the item in question.

Witnesses were called to speak to character.

Verdict: Guilty – one month's imprisonment.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 29 January 1850

The Pavilion Hotel: It is said that the new proprietor (Mr. Breach)

intends to make various alterations and additions to the Pavilion,

with a view to render that accommodation so much wanted in the

season.

Letter: In reference to your report respecting the trial of Osborne

and another for a robbery at the Pavilion, Folkestone, I merely

wish, in justice to myself, that you will state what appeared to the

Court, viz., that I gave the information to the policeman that was

the means of the man Osborne being convicted. I trust you will

insert a line or two in my favour to exonerate me from public

obloquy. Your most obedient servant, John Myers, Hythe, Jan. 27,

1850.

|

|

Dover Chronicle 2 February 1850

The Pavilion Hotel: It is said that the new proprietor (Mr. Breach)

intends to make various alterations and additions to the Pavilion,

with a view to render that accommodation so much wanted in the

season.

|

|

Kentish Gazette, 15 January 1850

The Pavilion Hotel is about to change hands. We understand that it has been

taken by Mr. Breach, of the firm of Battle and Breach, of the London Tavern,

Bishopsgate Street.

On Tuesday last, the quarter sessions for the borough of Folkestone were holden

at the Guildball, Folkestone, before the Recorder (J. J. Lonsdale, Esq.,) the

Mayor (D. Major, Esq.,) and Messrs. C. Golder, Wm. Major, and S. Bateman,

magistrates.

James Osborne, labourer, late of Hythe, was indicted for having stolen a piece

of copper, value 9d., the property of Mr. Owen Fickell Algar, proprietor of the

Pavilion Hotel.

Guilio Giovarni, manager of the Pavilion Hotel, deposed that the piece of copper

was brought to him by Pearson, the policeman, and which he recognised as being

the top of a “bain marie” It had not been used for two years; originally coat

25s.; and had been put away in the scullery.

Matthew Pearson, policeman, on the 25th of December, went to John Myers, the

marine store dealer, at Hythe, in consequence of information he had received;

saw the piece of copper produced; asked where it came from; was told by Myers

that he had purchased it from the ostler of the Duke’s Head Inn, named Osborn

Lee; took it away and brought it home; next day took it to the Pavilion Hotel,

where the servants identified it as being the property of Mr. Algar.

John Myers, marine-store dealer, deposed that Osborn Lee, ostler of the Duke’s

Head, brought the piece of copper produced; asked him how he came by it; said it

was all right; told him all right was sometimes all wrong; gave him 4s. for it,

but told him he might have the difference in the price, if any, at some future

time; did not know the exact value; told him, over and over again, he was afraid

it was stolen.

The Recorder cautioned this witness about his dealings, and told him to be more

cautious in future.

Osborn Lee, ostler at the Duke’s Head, Hythe, deposed to selling the piece of

copper for Osborne, without any suspicion that it had been stolen.

Mary Roker, still-room maid at the hotel, identified the copper as belonging to

the “bain marie” at the Pavilion. Saw it last in the still-room, two or three

years since.

William Francis, whitesmith, identified the copper produced, it being fitted by

him in the place it occupied.

The prisoner, on being asked what he had to say, stated that about a fortnight

ago he was sent for a load of ashes. One of his master's sweeps was down the

ash-hole at the Pavilion Hotel; he passed the piece of copper through the hole,

and when be (prisoner) cautioned him about it, he said all thrown in there

belonged to the sweeps. The sweep asked him to sell it for him, and he passed it

to Osborn Lee for the purpose.

The Recorder summed up, and the jury, having retired for a short time, acquitted

the prisoner. He was, however, detained in custody, to be brought up as evidence

against the sweep.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 19 February 1850

At the Petty Sessions on Tuesday the licence of the South Eastern

Pavilion was transferred from T. Algar to James Gaby Breach, of the

London Tavern, Bishopsgate, London, and the licence of the

Oddfellows Arms was transferred from Edward Brooks to Frances

Shovler.

Note: Oddfellows Arms; Earlier end date for Brooks – and different

first name. Shovler previously unknown.

|

|

Kent Herald, 21 February 1850.

Petty Sessions: At the Petty Sessions the license of the "South Eastern Pavilion"

was transferred from T. Alger to James Gaby Breach, of the London Tavern, Bishopsgate,

London.

|

|

Dover Chronicle 23 February 1850

At the Petty Sessions on Tuesday the licence of the "South Eastern

Pavilion" was transferred from T. Algar to James Gaby Breach, of the

"London Tavern.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 26 February 1850

Petty Sessions, Monday; Before D. Major Esq., Mayor, W. Major and S.

Mackie Esqs.

James Driscall, of Hythe, master chimney sweeper, was charged with

having, on the 12th inst., stolen a chimney sweeping machine, value

£10, from the Pavilion Hotel, the property of James Gaby Breach.

Guilio Giovannini deposed: When I was manager of the Pavilion Hotel,

I repeatedly missed different articles belonging to it. The sweeping

machine now produced is the property of Mr. Breach; it has been in

use at the hotel. The last time I saw the machine was about three

weeks ago, and on Thursday last I missed it. I never gave James

Driscall permission to take the machine. He must have taken it away

from part of the house where he had no business. I have known that

there was a machine belonging to the house about two years.

James Gaby Breach deposed: I am proprietor of the said hotel, and as

such the sweeping machine belongs to me. One day in the early part

of last week I was in the basement storey of the hotel. I saw

Driscall in the lower part of the house, and asked him what business

he had there; he said “I want to see Mr. Giavannini”. I said that

was not the place to find him, and told him to go upstairs. I saw a

boy with him carrying the machine, and asked Driscall what he was

going to do with it. He said “I am going to take it away, as it

belongs to me”. I then suffered him to take it away, as I did not at

that time know it belonged to me. The prisoner had no business

whatever in the hotel where I found him.

Frederick George Francis deposed: When my father used to sweep the

chimneys at the hotel, I bought two machines for the use of the

house. There are no particular marks on the machine, but I believe

it is the one belonging to the Pavilion Hotel. I have frequently

used the machine myself. I know it by the sticks being much shorter

than those usually used by sweeps.

Matthew Pearson, police constable, deposed that he found the machine

in the premises belonging to James Driscall.

The prisoner was committed for trial, but liberated on bail.

|

|

Kent Herald, 28 February 1850.

Petty Sessions: James Driscall, of Hythe, master chimney sweeper, was charged

with having, on the 12th inst., stolen a chimney sweeping machine, value £10,

from the Pavilion Hotel, the property of James Gaby Breach. After taking

evidence, the prisoner was committed for trial, but liberated on bail.

|

|

Dover Chronicle 27 April 1850

Folkestone Quarter Sessions, before W. Lonsdale Esq., Recorder.

John Driscoll, master sweep, of Hythe, was indicted for stealing a

sweeping apparatus, or machine, from the Pavilion, at Folkestone.

Mr. Sladden prosecuted, and Mr. Mercer, of Ashford, defended.

It appeared that the article was taken under the idea that it was

his own property, and that this was stated to the prosecutor, Mr.

Breach, master of the hotel, at the time the prisoner took the

article in question, and the Jury, after an able defence from the

prisoner's advocate, returned a verdict of Not Guilty.

|

|

Maidstone Gazette 30 April 1850

Folkestone Quarter Sessions, yesterday week, before J.J. Lonsdale

Esq., Recorder.

James Driscall, master sweep, residing at Hythe, was indicted for

feloniously stealing one sweeping machine, value £10, the property

of James Gaby Breach.

James Gaby Breach deposed: I have been the occupier of the Pavilion

Hotel since the 13th January last. About the second week of February

I met the prisoner in the basement of the premises with a sweeping

machine. I asked him what he did there; he told me he was looking

for Mr. Giovannini. I told him that was not the place to look for

him, but in his office; he was going in the direction of the steps

into the road above. I asked him if the machine was mine; he said

“No, his own, and he was going to take it home”. I afterwards

discovered that the one belonging to me was gone. I believe the one

the prisoner had was mine; it was part of the fixtures of the house,

and included in the inventory when I took the hotel. The prisoner

had no business in the hotel, as his contract was terminated and his

account settled.

The witness, in cross-examination, stated that he was not sure that

the machine was in the inventory, but he believed it was. He had not

prosecuted one of the prisoner's servants for theft; he had heard

that one had been tried and convicted before he took possession of

the hotel.

Gulion Giovannini deposed: I hold a situation at the Pavilion Hotel,

as manager, and have done so about 4½ years. The prisoner succeeded

a Mr. Francis as sweep, and a contract was entered into and the

machine was handed over by Francis to the prisoner, for his use in

the hotel.

Cross-examined: I recollect seeing the machine, but do not recollect

if it was in the dust-hole; it had short sticks like the one in

Court; the prisoner had no business to take it away. Before I paid

the prisoner his account, I sent the policeman, Pearson, to the

prisoner's to request him to send back the machine belonging to the Pavilion,

and he did so. Did not know how long a machine would last; had never

used one (laughter). Never looked to see if the machine was kept in

the dust-hole; that was not his business. Had never been called upon

to repair the machine. When the agreement to sweep the chimneys was

made, other parties were present. The prisoner was to have £16 a

year for it, and to pay £5 yearly for the ashes. He had prosecuted

the prisoner's servant, Thomas Graham, for stealing a

piece of copperfrom the dust-hole.

Frederick Francis deposed: I do the smith's work at the Pavilion. My

father used to sweep the chimneys by contract when I was in London.

My father wrote to me to purchase two machines of the Ramoncur

Company in 1845. I sent them down and received the money for them;

they were numbered 101 and 102; the heads produced are those I

purchased, and were in use at the Pavilion Hotel. The canes are

similar in appearance. I understood they were for the South Eastern

Railway Company, and that Mr. Sims, the foreman, paid my father for

them.

Mr. Mercer addressed the jury for the defence, and observed that the

prisoner was indicted for feloniously stealing a certain machine,

the property of one James Gaby Breach, but he could prove to them

that the machine never was his property; that on the prisoner taking

the contract from Francis he was told by him that he might have the

machine, and he had always considered it his own. The prisoner's

conduct throughout was that of an honest man; he had never applied

to the proprietors of the Pavilion to repair the machine at any

time, and when he found they claimed a machine, he took the one away