|

From the Whitstable Times, 24 September, 1870.

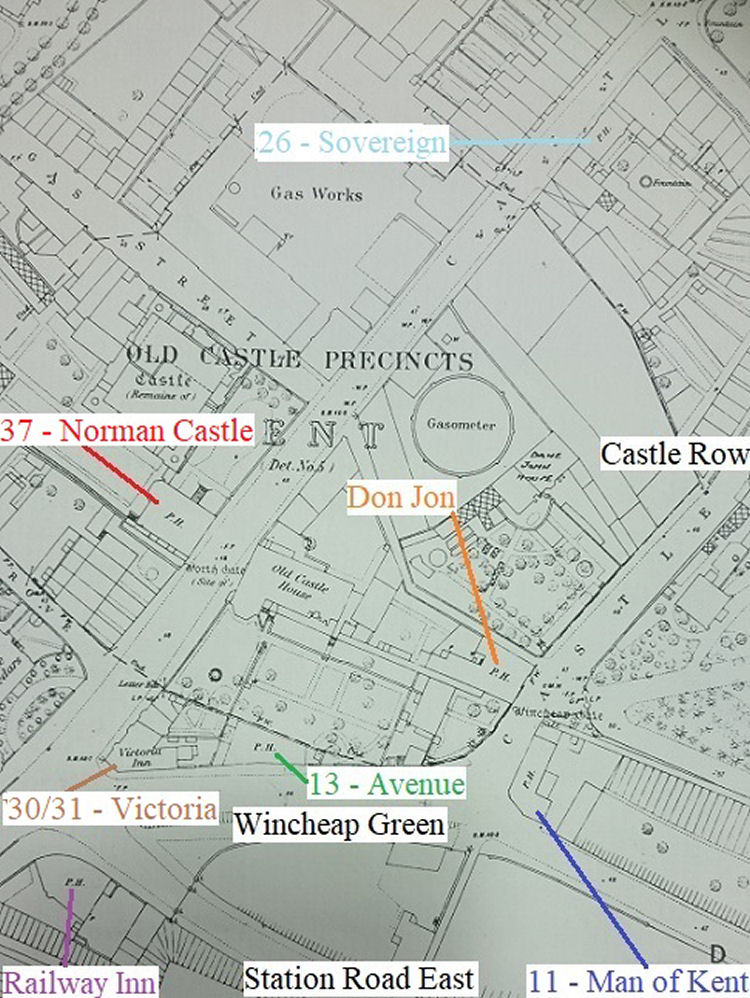

IMPORTANT PROCEEDINGS AGAINST THE CANTERBURY GAS AND WATER COMPANY.

At the city Police Court, on Thursday, (before H. G. Austin, Esq., in

the chair, Alderman Masters, J. Hemery, Esq., and H. Cooper, Esq.,) the

Directors of the Canterbury Gas and Water Company were summoned for

poisoning wells in Castle-street, by allowing a leakage to exist at

their gas works twenty-four hours after notice had been given to the

company.

Mr. Webster, barrister, appeared far plaintiff; Mr. Bealey for the

defendants.

George Felix Finn, landlord of the “Sovereign,” was the complainant in

the first case.

In opening the proceedings, Mr. Webster remarked that the object of the

plaintiffs in taking out summonses against the company was not expressly

for extorting heavy penalties, but more for securing a pure supply of

water in future. In the case now before the Bench, the facts were

these:— Up to the commencement of the year, plaintiff had been supplied

with water through the company's old mains, the well on his premises

having far some time been closed, in consequence of the offsets of a

leakage from the gas works. Prior to opening the well, plaintiff

received a notice, from the directors, informing him that, as they had

adopted new works, the old supply would be discontinued; and Finn,

having a desire to make use of the well, determined to have it

re-opened, upon doing which the water therein was found to be poisoned

by being contaminated with percolations from the gas works. On making a

complaint of this, Finn was told he would find, if he emptied the well

of its contents, the new water which came in would be pure. Of course he

was only too pleased to try the experiment. The prospects held out were

not realised, however; the fresh water, as it found its way into the

well from the springs, being still more impregnated then that which was

taken out. The plaintiff was, therefore, induced to serve the company

with a notice on the 24th of August. Having observed that the company

had been re-incorporated, Mr. Webster proceeded to draw attention to the

Act of Parliament and to the clause defining the penalty to which the

company was subjected for creating such an offence—viz., a sum not

exceeding £200 as penalty, and £10 for every day that elapse after the

expiration of twenty-four hours after the service of the notice if the

evil is not remedied. He did not know what defence Mr. Bealey could make

to the charge—whether or not he would deny there was any leakage at all,

after the meetings the directors had held upon the subject of

contamination, and the resolution agreed to by them, whereby they

proposed terms to these whose wells had been injured; and surely after

this it could not be reasonable for them to come here and deny that any

leakage existed. There was no doubt whatever that the ammoniacal water

did escape from the gas-holder tank, that it percolated the soil, and

poisoned the water in the neighbouring wells, and it was for the purpose

of having their rights re-instated that the aggrieved persons had

instituted these proceedings.

The magistrates' clerk having read the notice served upon the directors,

which it appeared was worded under the auspices of the old company, the

following evidence was produced by Mr. Webster:

George Felix Finn deposed:— I have occupied the “Sovereign Inn” for a

period of five years, and during the greater part of that time I have

been supplied with water through the old pipes of the company. On

receiving a notice stating that the old supply would be discontinued and

a new one introduced, I determined to open the well in my cellar for the

purpose of ascertaining whether the water from the springs was pure, and

for this purpose I took the old water out and let the fresh in. The new

water as it came in was strongly impregnated with gas, which was

perceptible both as regards taste and smell. I examined the well also on

a subsequent occasion, with the same result, and have tested the water

again this morning, finding it still poisoned.

Mr. Webster was about asking Finn whether he was not aware of his own

knowledge that other wells in the locality had been similarly poisoned,

when Mr. Besley objected to the question, contending that the

magistrates were there simply investigating a complaint made by Finn,

not affecting any one else.

Mr. Webster appealed to the Bench. If the same means of poisoning the

plaintiffs well affected other wells, he argued that he had a right to

ask the question.

The magistrates thought it would be more in order for Mr. Webster to

confine himself to the case in which Mr. Finn was plaintiff.

Mr. Finn, in continuing his statement, said he remembered opening the

well in 1867, when the water appeared to be clear and good.

Cross-examined by Mr. Besley:— Under the old supply I had four taps in

my house from which I could obtain water—one in the cellar, two on the

ground floor, and one upstairs. Up to the time the old supply was cut

off I had the water gratuitously.

I prefer using well water, which I consider superior.

I believe there was a leakage from the gas-holder tank in 1854, but I

was not occupier of the “Sovereign” then. I had a supply of gas from the

company up to March, 1869, when I discontinued being a customer, and the

gas was cut off by my order. The escape which poisons my well could not

have emanated from the gas pipes, as the well is 3 ft. below them. I was

aware I had power to dig up the ground to ascertain if there was any

leakage from the main pipe, which is 15ft. or 20ft. from the well; but I

did not do so, as I did not think it probable the pollution took place

through any escape from the main. There was a cesspool 16ft. away from

the well. I admit that I want a conviction, and I suppose the penalty

will follow.

Re-examined:— I did not come here particularly to seek damages, but to

ensure a good supply of water, and to regain the exercise of my rights.

I did all I could to arrange the matter previously, but as I could not

agree to the terms offered by the company, I resorted to these

proceedings. If I had taken the new water, I should have expected to

have paid for it.

Mr. Webster said a suggestion having been thrown out that drainage might

be the cause of the pollution, he would call Mr. Cole to state to the

contrary.

George Cole, plumber and glazier, stated that in the coarse of his

experience he had opened seven wells, on examining the plaintiffs so

found the water strongly impregnated with gas, so much so indeed, as to

induce him to be positive that an escape of water from the gas-holder

tank was the cause thereof. The water in the bottle produced did not

bear traces of gas pollution, and it must have been taken from the top,

where the poisonous matter was not so perceptible as at the bottom.

Several meetings of persons who considered themselves aggrieved by being

deprived of the use of their wells had been held on different occasions,

and a deputation waited upon the directors, who passed a resolution

stating that water from the new works would be supplied at half price to

these persons whose wells appeared to be impregnated with gas, after an

examination had been made by their officer; but if the water was found

to be pure, the ordinary rate would be charged.

This being the conclusion of the case for the plaintiff,

Mr. Besley addressed the magistrates on behalf of the directors, and

firstly asked them to give their decision on the point whether the case

was properly before them. The wording of the notion he contended was not

correct, though that of the summer was; for in the former the directors

were indefinitely charged with allowing a leakage of gas washings,

whereas the formal and correct term specified by the Act was simply gas.

He made this objection because he urged that before a conviction could

be recorded it must be shown there was a leakage of gas; whereas up to

the present time no evidence had been called that related to anything

but gas washings. The mistake was evidently made by the notice being

framed under erroneous auspices—viz., an old Act of Parliament.

Mr. Webster said he must protest against any objection as to

jurisdiction being entertained at this advanced stage of the

proceedings.

The magistrates considered this was an improper time to raise such an

objection. It should have been made when the case was first brought

before them, and not at the adjourned hearing. The case was postponed at

their own instigation.

Mr. Besley, in resuming his address, alluded to the important nature of

the decision that would be given by the Bench upon the merits of the

case, which he asked them to balance well. They all knew how essential

it was that successful issue should attend joint stock enterprise; yet

of course he would not for a moment wish them to infer that in their

operations they were justified in poisoning wells or in injuring any

person; but especially in a company supplying two such important

elements in the enjoyment of life as gas and water was it desirable that

their management should be successful. If any grievance existed in this

instance it was not one for which the present company could be

considered responsible, but one which originated in 1854, and which had

been condoned for by an arrangement between the parties that they should

be supplied with water gratuitously, and the supply had been continued

under these circumstances ever since. Up to the time of the new works

being opened at the period, to which he referred back, there was an

escape from the gas-holder tank, caused by pure accident, and for which

no one was to blame. This was, however, as he had said, settled, by the

company giving a supply from their own works; and the question for

adjudication by the magistrates was whether they would convict the

company of an act committed in 1854, the pollution then accruing from

that which had now been remedied, as he should conclusively show in

evidence, as well as the fact that no offence had been committed during

the past six months, the time prescribed by the Act. He might remark

that the directors could not understand the necessity of the summonses

against them being multiplied, the others well knowing this case was

coming on; and if they meant to harass the directors he must ask the

Bench to consider whether the evidence in the first case justified them

in going into the others. He then called the following evidence: Harry

Good, manager of the company from 1839 to 1886, stated that about the

year 1852 a complaint was made of the leakage from the gas-holder tank,

and an arrangement was made with the occupier of the “Sovereign” on

account of the poisoning of his well. Mr. Webster did not see how this

agreement, made with a previous tenant to Finn’s predecessor, could in

any way be taken to relate to the present case. He objected to such

evidence being taken The Bench also thought it had no bearing upon the

summons.

Mr. Good continued:— The water round the gasholder was for sealing the

vessel. The tank is 40ft. deep. (Witness afterwards corrected this part

of his evidence, stating the depth was 16ft.) At the time he alluded to,

the holder was out of repair, the puddling with which it was encircled

being defective. Attempts were made to repair it, but it was not made a

good job.

Edward Eves, inspector, said the water was put on at the “Sovereign” in

1856, and was continued up to last year. There was no leakage whatever

in that neighbourhood at the present time. In cross-examination, he

admitted he had not taken up all the mains.

Robert K. Moorhouse, the present manager, said there had been no leakage

from the gas-holder tank since he had been manager; if there had, he

should have found it out by the quantity in the decreasing; and it had

not been found necessary to pump fresh water in.

Cross-examined:— Altogether, they had three tanks, two of which had

required water, but the one on the same side of the road as plaintiff’s

house had not.

Mr. James Burch, secretary, said in 1868 the gasholder tank in question

was found to leak, and by order of the directors it was emptied and

repaired thoroughly. In July last year he tested the retentive powers of

the tank, by taking the level of the water twice—the second time,

twenty-four hours after the first, when he found the level precisely the

same.

Cross-examined:— He had nothing to do with the practical management of

the works. There was a leakage from one of the tanks, but this was

seventy yards away from the plaintiff’s premises. There was no leakage

from the one near the “Sovereign.”

This being the whole of the evidence, the magistrate retired, and after

some deliberation they returned into Court; when the Chairman said they

had unanimously arrived at the decision that the case was proved. They

fined the company £30 penalty, and ordered them to pay 10s. for every

day after twenty-four hours since the service of the notice. The Court

would be adjourned until three, when the other cases would be heard.

Mr. Beeley stated that as the directors intended to appeal, they hoped

the other cases would not be gone into at present.

Mr. Webster had no objection to their being adjourned, but as the

circumstances were different in each case, one decision could not, he

thought, apply to all the summonses.

The cases were then adjourned until the 24th of October.

|